France had now occupied the valley of the Mississippi and joined with loose and uncertain links her two colonies of Canada and Louisiana.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 17.

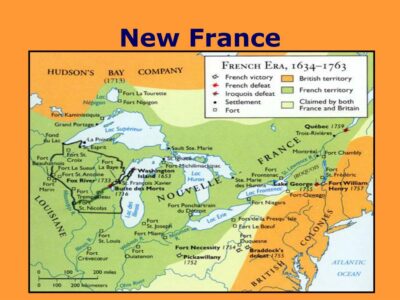

Yet so jealous were the Iroquois of a French fort at Niagara that they sent three Seneca chiefs to see what was going on there. The chiefs found a few Frenchmen in a small blockhouse, or loopholed storehouse, which they had just built near Lewiston Heights. The three Senecas requested them to demolish it and go away, which the Frenchmen refused to do; on which the Senecas asked the English envoys, Schuyler and Livingston, to induce the governor of New York to destroy the obnoxious building. In short, the Five Nations wavered incessantly between their two European neighbors and changed their minds every day. The skill and perseverance of the French emissaries so far prevailed at last that the Senecas consented to the building of a fort at the mouth of the Niagara, where Denonville had built one in 1687; and thus, that important pass was made tolerably secure.

Yet so jealous were the Iroquois of a French fort at Niagara that they sent three Seneca chiefs to see what was going on there. The chiefs found a few Frenchmen in a small blockhouse, or loopholed storehouse, which they had just built near Lewiston Heights. The three Senecas requested them to demolish it and go away, which the Frenchmen refused to do; on which the Senecas asked the English envoys, Schuyler and Livingston, to induce the governor of New York to destroy the obnoxious building. In short, the Five Nations wavered incessantly between their two European neighbors and changed their minds every day. The skill and perseverance of the French emissaries so far prevailed at last that the Senecas consented to the building of a fort at the mouth of the Niagara, where Denonville had built one in 1687; and thus, that important pass was made tolerably secure.

Meanwhile the English of New York, or rather Burnet, their governor, were not idle. Burnet was on ill terms with his assembly, which grudged him all help in serving the province whose interests it was supposed to represent. Burnet’s plan was to build a fortified trading-house at Oswego, on Lake Ontario, in the belief that the western Indians, who greatly preferred English goods and English prices, would pass Niagara and bring their furs to the new post. He got leave from the Five Nations to execute his plan, bought canoes, hired men, and built a loopholed house of stone on the site of the present city of Oswego. As the Assembly would give no money, Burnet furnished it himself; and though the object was one of the greatest importance to the province, he was never fully repaid.[1] A small garrison for the new post was drawn from the four independent companies maintained in the province at the charge of the Crown.

[1: “I am ashamed to confess that he built the fort at his private expense, and that a balance of above £56 remains due to his estate to this very day.” — Smith, History of New York, 267 (ed. 1814).]

The establishment of Oswego greatly alarmed and incensed the French, and a council of war at Quebec resolved to send two thousand men against it; but Vaudreuil’s successor, the Marquis de Beauharnois, learning that the court was not prepared to provoke a war, contented himself with sending a summons to the commanding officer to abandon and demolish the place within a fortnight.[2] To this no attention was given; and as Burnet had foreseen, Oswego became the great center of Indian trade, while Niagara, in spite of its more favorable position, was comparatively slighted by the western tribes. The chief danger rose from the obstinate prejudice of the Assembly, which, in its disputes with the Royal Governor, would give him neither men nor money to defend the new post.

[2: Mémoire de Dupuy, 1728. Dupuy was intendant of Canada. The King approved the conduct of Beauharnois in not using force. Dépêche du Roy, 14 Mai, 1728.]

The Canadian authorities, who saw in Oswego an intrusion on their domain and a constant injury and menace, could not attack it without bringing on a war, and therefore tried to persuade the Five Nations to destroy it, — an attempt which completely failed.[3] They then established a trading-post at Toronto, in the vain hope of stopping the northern tribes on their way to the more profitable English market, and they built two armed vessels at Fort Frontenac to control the navigation of Lake Ontario.

[3: When urged by the younger Longueuil to drive off the English from Oswego, the Indians replied, “Drive them off thyself” (“Chassez-les toi-même”). Longueuil fils au Ministre, 19 Octobre, 1728.]

Meanwhile, in another quarter the French made an advance far more threatening to the English colonies than Oswego was to their own. They had already built a stone fort at Chambly, which covered Montreal from any English attack by way of Lake Champlain. As that lake was the great highway between the rival colonies, the importance of gaining full mastery of it was evident. It was rumored in Canada that the English meant to seize and fortify the place called Scalp Point (Pointe à la Chevelure) by the French, and Crown Point by the English, where the lake suddenly contracts to the proportions of a river, so that a few cannon would stop the passage.

As early as 1726 the French made an attempt to establish themselves on the east side of the lake opposite Crown Point but were deterred by the opposition of Massachusetts. This eastern shore was, however, claimed not only by Massachusetts, but by her neighbor, New Hampshire, with whom she presently fell into a dispute about the ownership, and, as a writer of the time observes, “while they were quarrelling for the bone, the French ran away with it.”

[Mitchell, Contest in America, 22.]

At length, in 1731, the French took post on the western side of the lake, and began to intrench themselves at Crown Point, which was within the bounds claimed by New York; but that province, being then engrossed, not only by her chronic dispute with her governor, but by a quarrel with her next neighbor, New Jersey, slighted the danger from the common enemy, and left the French to work their will. It was Saint-Luc de la Corne, Lieutenant du Roy at Montreal, who pointed out the necessity of fortifying this place,[4] in order to anticipate the English, who, as he imagined, were about to do so, — a danger which was probably not imminent, since the English colonies, as a whole, could not and would not unite for such a purpose, while the individual provinces were too much absorbed in their own internal affairs and their own jealousies and disputes to make the attempt. La Corne’s suggestion found favor at court, and the governor of Canada was ordered to occupy Crown Point. The Sieur de la Fresnière was sent thither with

troops and workmen, and a fort was built, and named Fort Frédéric. It contained a massive stone tower, mounted with cannon to command the lake, which is here but a musket-shot wide. Thus was established an advanced post of France, — a constant menace to New York and New England, both of which denounced it as an outrageous encroachment on British territory, but could not unite to rid themselves of it.[5]

[4: La Corne au Ministre, 15 Octobre, 1730.]

[5: On the establishment of Crown Point, Beauharnois et Hocquart au Roy, 10 Octobre, 1731; Beauharnois et Hocquart au Ministre, 14 Novembre, 1731.]

While making this bold push against their neighbors of the South, the French did not forget the West; and towards the middle of the century they had occupied points controlling all the chief waterways between Canada and Louisiana. Niagara held the passage from Lake Ontario to Lake Erie. Detroit closed the entrance to Lake Huron, and Michilimackinac guarded the point where Lake Huron is joined by Lakes Michigan and Superior; while the fort called La Baye, at the head of Green Bay, stopped the way to the Mississippi by Marquette’s old route of Fox River and the Wisconsin. Another route to the Mississippi was controlled by a post on the Maumee to watch the carrying-place between that river and the Wabash, and by another on the Wabash where Vincennes now stands. La Salle’s route, by way of the Kankakee and the Illinois, was barred by a fort on the St. Joseph; and even if, in spite of these obstructions, an enemy should reach the Mississippi by any of its northern affluents, the cannon of Fort Chartres would prevent him from descending it.

These various western forts, except Fort Chartres and Fort Niagara, which were afterwards rebuilt, the one in stone and the other in earth, were stockades of no strength against cannon. Slight as they were, their establishment was costly; and as the King, to whom Canada was a yearly loss, grudged every franc spent upon it, means were contrived to make them self-supporting. Each of them was a station of the fur-trade, and the position of most of them had been determined more or less with a view to that traffic. Hence, they had no slight commercial value. In some of them the Crown itself carried on trade through agents who usually secured a lion’s share of the profits. Others were farmed out to merchants at a fixed sum. In others, again, the commanding officer was permitted to trade on condition of maintaining the post, paying the soldiers, and supporting a missionary; while in one case, at least, he was subjected to similar obligations, though not permitted to trade himself, but only to sell trading licenses to merchants. These methods of keeping up forts and garrisons were of course open to prodigious abuses and roused endless jealousies and rivalries.

France had now occupied the valley of the Mississippi and joined with loose and uncertain links her two colonies of Canada and Louisiana. But the strength of her hold on these regions of unkempt savagery bore no proportion to the vastness of her claims or the growing power of the rivals who were soon to contest them.

The Peace of Utrecht left unsettled the perilous questions of boundary between the rival powers in North America, and they grew more perilous every day. Yet the quarrel was not yet quite ripe; and though the French governor, Vaudreuil, and perhaps also his successor, Beauharnois, seemed willing to precipitate it, the courts of London and Versailles still hesitated to appeal to the sword. Now, as before, it was a European, and not an American, quarrel that was to set the world on fire. The War of the Austrian Succession broke out in 1744. When Frederic of Prussia seized Silesia and began that bloody conflict, it meant that packs of howling savages would again spread fire and carnage along the New England border.

News of the declaration of war reached Louisbourg some weeks before it reached Boston, and the French military governor, Duquesnel, thought he saw an opportunity to strike an unexpected blow for the profit of France and his own great honor.

One of the French inhabitants of Louisbourg has left us a short sketch of Duquesnel, whom he calls “capricious, of an uncertain temper, inclined to drink, and when in his cups neither reasonable or civil.”[6] He adds that the governor had offended nearly every officer in the garrison, and denounces him as the “chief cause of our disasters.” When Duquesnel heard of the declaration of war, his first thought was to strike some blow before the English were warned. The fishing-station of Canseau was a tempting prize, being a near and an inconvenient neighbor, at the southern end of the Strait of Canseau, which separates the Acadian peninsula from the island of Cape Breton, or Isle Royale, of which Louisbourg was the place of strength. Nothing was easier than to seize Canseau, which had no defense but a wooden redoubt built by the fishermen, and occupied by about eighty Englishmen thinking no danger. Early in May, Duquesnel sent Captain Duvivier against it, with six hundred, or, as the English say, nine hundred soldiers and sailors, escorted by two small armed vessels. The English surrendered, on condition of being sent to Boston, and the miserable hamlet, with its wooden citadel, was burned to the ground.

[6: Lettre d’un Habitant de Louisbourg contenant une Relation exacte et circonstanciée de la Prise de l’Isle Royale par les Anglois.]

Thus far successful, the governor addressed himself to the capture of Annapolis, — which meant the capture of all Acadia. Duvivier was again appointed to the command. His heart was in the work, for he was a descendant of La Tour, feudal claimant of Acadia in the preceding century. Four officers and ninety regular troops were given him,[7] and from three to four hundred Micmac and Malicite Indians joined him on the way. The Micmacs, under command, it is said, of their missionary, Le Loutre, had already tried to surprise the English fort, but had only succeeded in killing two unarmed stragglers in the adjacent garden.[8]

[7: Lettre d’un Habitant de Louisbourg.]

[8: Mascarene to the Besiegers, 3 July, 1744. Duquesnel had written to all the missionaries “d’engager les sauvages à faire quelque coup important sur le fort” (Annapolis). Duquesnel à Beauharnois, 1 Juin, 1744.]

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 18 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.