France claims all North America except for those lands claimed by Spain.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Beginning Chapter 17.

We have seen that the contest between France and England in America divided itself, after the Peace of Utrecht, into three parts, — the Acadian contest; the contest for northern New England; and last, though greatest, the contest for the West. Nothing is more striking than the difference, or rather contrast, in the conduct and methods of the rival claimants to this wild but magnificent domain. Each was strong in its own qualities, and utterly wanting in the qualities that marked its opponent.

We have seen that the contest between France and England in America divided itself, after the Peace of Utrecht, into three parts, — the Acadian contest; the contest for northern New England; and last, though greatest, the contest for the West. Nothing is more striking than the difference, or rather contrast, in the conduct and methods of the rival claimants to this wild but magnificent domain. Each was strong in its own qualities, and utterly wanting in the qualities that marked its opponent.

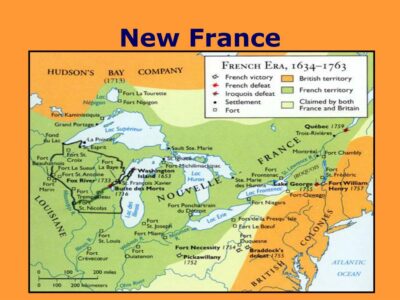

On maps of British America in the earlier part of the eighteenth century, one sees the eastern shore, from Maine to Georgia, garnished with ten or twelve colored patches, very different in shape and size, and defined, more or less distinctly, by dividing-lines which, in some cases, are prolonged westward till they touch the Mississippi, or even cross it and stretch indefinitely towards the Pacific. These patches are the British provinces, and the westward prolongation of their boundary lines represents their several claims to vast interior tracts, founded on ancient grants, but not made good by occupation, or vindicated by any exertion of power.

These English communities took little thought of the region beyond the Alleghanies. Each lived a life of its own, shut within its own limits, not dreaming of a future collective greatness to which the possession of the West would be a necessary condition. No conscious community of aims and interests held them together, nor was there any authority capable of uniting their forces and turning them to a common object. Some of the servants of the Crown had urged the necessity of joining them all under a strong central government, as the only means of making them loyal subjects and arresting the encroachments of France; but the scheme was plainly impracticable. Each province remained in jealous isolation, busied with its own work, growing in strength, in the capacity of self-rule and the spirit of independence, and stubbornly resisting all exercise of authority from without. If the English-speaking populations flowed westward, it was in obedience to natural laws, for the King did not aid the movement, the royal governors had no authority to do so, and the colonial assemblies were too much engrossed with immediate local interests. The power of these colonies was that of a rising flood slowly invading and conquering, by the unconscious force of its own growing volume, unless means be found to hold it back by dams and embankments within appointed limits.

In the French colonies all was different. Here the representatives of the Crown were men bred in an atmosphere of broad ambition and masterful and far-reaching enterprise. Achievement was demanded of them. They recognized the greatness of the prize, studied the strong and weak points of their rivals, and with a cautious forecast and a daring energy set themselves to the task of defeating them.

If the English colonies were comparatively strong in numbers, their numbers could not be brought into action; while if the French forces were small, they were vigorously commanded, and always ready at a word. It was union confronting division, energy confronting apathy, military centralization opposed to industrial democracy; and, for a time, the advantage was all on one side.

The demands of the French were sufficiently comprehensive. They repented of their enforced concessions at the Treaty of Utrecht, and in spite of that compact, maintained that, with a few local and trivial exceptions, the whole North American continent, except Mexico, was theirs of right; while their opponents seemed neither to understand the situation, nor see the greatness of the stakes at issue.

In 1720 Father Bobé, priest of the Congregation of Missions, drew up a paper in which he sets forth the claims of France with much distinctness, beginning with the declaration that “England has usurped from France nearly everything that she possesses in America,” and adding that the plenipotentiaries at Utrecht did not know what they were about when they made such concessions to the enemy; that, among other blunders, they gave Port Royal to England when it belonged to France, who should “insist vigorously” on its being given back to her.

He maintains that the voyages of Verrazzano and Ribaut made France owner of the whole continent, from Florida northward; that England was an interloper in planting colonies along the Atlantic coast, and will admit as much if she is honest, since all that country is certainly a part of New France. In this modest assumption of the point at issue, he ignores John Cabot and his son Sebastian, who discovered North America more than twenty-five years before the voyage of Verrazzano, and more than sixty years before that of Ribaut.

When the English, proceeds Father Bobé, have restored Port Royal to us, which they are bound to do, though we ceded it by the treaty, a French governor should be at once set over it, with a commission to command as far as Cape Cod, which would include Boston. We should also fortify ourselves, “in a way to stop the English, who have long tried to seize on French America, of which they know the importance, and of which,” he observes with much candor, “they would make a better use than the French do.[1] The Atlantic coast, as far as Florida, was usurped from the French, to whom it belonged then, and to whom it belongs now.” England, as he thinks, is bound in honor to give back these countries to their true owner; and it is also the part of wisdom to do so, since by grasping at too much, one often loses all. But France, out of her love of peace, will cede to England the countries along the Atlantic, from the Kennebec in New France to the Jordan[2] in Carolina, on condition that England will restore to her all that she gave up by the Treaty of Utrecht. When this is done, France, always generous, will consent to accept as boundary a line drawn from the mouth of the Kennebec, passing thence midway

between Schenectady and Lake Champlain and along the ridge of the Alleghanies to the river Jordan, the country between this line and the sea to belong to England, and the rest of the continent to France.

[1: “De manière qu’on puisse arrêter les Anglois, qui depuis longtems tachent de s’emparer de l’Amérique françoise, dont ils conoissent l’importance et dont ils feroient un meillieur usage que celuy qui les françois en font.”]

[2: On the river Jordan, so named by Vasquez de Ayllon, see “Pioneers of France in the New World,” 11, 39, note. It was probably the broad river of South Carolina.]

If England does not accept this generous offer, she is to be told that the King will give to the Compagnie des Indes (Law’s Mississippi Company) full authority to occupy “all the countries which the English have usurped from France;” and, pursues Father Bobé, “it is certain that the fear of having to do with so powerful a company will bring the English to our terms.” The company that was thus to strike the British heart with terror was the same which all the tonics and stimulants of the government could not save from predestined ruin. But, concludes this ingenious writer, whether England accepts our offers or not, France ought not only to take a high tone (parler avec hauteur), but also to fortify diligently, and make good her right by force of arms.

[Second Mémoire concernant les Limites des Colonies présenté en 1720 par Bobé, prêtre de la Congrégation de la Mission (Archives Nationales).]

Three years later we have another document, this time of an official character, and still more radical in its demands. It admits that Port Royal and a part of the Nova Scotian peninsula, under the name of Acadia, were ceded to England by the treaty, and consents that she shall keep them, but requires her to restore the part of New France that she has wrongfully seized, — namely, the whole Atlantic coast from the Kennebec to Florida; since France never gave England this country, which is hers by the discovery of Verrazzano in 1524. Here, again, the voyages of the Cabots, in 1497 and 1498, are completely ignored.

“It will be seen,” pursues this curious document, “that our kings have always preserved sovereignty over the countries between the thirtieth and the fiftieth degrees of north latitude. A time will come when they will be in a position to assert their rights, and then it will be seen that the dominions of a king of France cannot be usurped with impunity. What we demand now is that the English make immediate restitution.” No doubt, the paper goes on to say, they will pretend to have prescriptive rights, because they have settled the country and built towns and cities in it; but this plea is of no avail, because all that country is a part of New France, and because England rightfully owns nothing in America except what we, the French, gave her by the Treaty of Utrecht, which is merely Port Royal and Acadia. She is bound in honor to give back all the vast countries she has usurped; but, continues the paper, “the King loves the English nation too much, and wishes too much to do her kindness, and is too generous to exact such a restitution. Therefore, provided that England will give us back Port Royal, Acadia, and everything else that France gave her by the Treaty of Utrecht, the King will forego his rights, and grant to England the whole Atlantic coast from the thirty-second degree of latitude to the Kennebec, to the extent inland of twenty French leagues [about fifty miles], on condition that she will solemnly bind herself never to overstep these limits or encroach in the least on French ground.”

Thus, through the beneficence of France, England, provided that she renounced all pretension to the rest of the continent, would become the rightful owner of an attenuated strip of land reaching southward from the Kennebec along the Atlantic seaboard. The document containing this magnanimous proposal was preserved in the Château St. Louis at Quebec till the middle of the eighteenth century, when, the boundary dispute having reached a crisis, and commissioners of the two powers having been appointed to settle it, a certified copy of the paper was sent to France for their instruction.

[Demandes de la France, 1723 (Archives des Affaires Étrangères).]

Father Bobé had advised that France should not trust solely to the justice of her claims, but should back right with might, and build forts on the Niagara, the Ohio, the Tennessee, and the Alabama, as well as at other commanding points, to shut out the English from the West. Of these positions, Niagara was the most important, for the possession of it would close the access to the Upper Lakes and stop the western tribes on their way to trade at Albany. The Five Nations and the governor of New York were jealous of the French designs, which, however, were likely enough to succeed, through the prevailing apathy and divisions in the British colonies. “If those not immediately concerned,” writes a member of the New York council, “only stand gazing on while the wolff is murthering other parts of the flock, it will come to every one’s turn at last.” The warning was well found, but it was not heeded. Again: “It is the policy of the French to attack one colony at a time, and the others are so besotted as to sit still.”

[Colonel Heathcote to Governor Hunter, 8 July, 1715. Ibid, to Townshend, 12 July, 1715.]

For gaining the consent of the Five Nations to the building of a French fort at Niagara, Vaudreuil trusted chiefly to his agent among the Senecas, the bold, skillful, and indefatigable Joncaire, who was naturalized among that tribe, the strongest of the confederacy. Governor Hunter of New York sent Peter Schuyler and Philip Livingston to counteract his influence. The Five Nations, who, conscious of declining power, seemed ready at this time to be all things to all men, declared that they would prevent the French from building at Niagara, which, as they said, would “shut them up as in a prison.”[3] Not long before, however, they had sent a deputation to Montreal to say that the English made objection to Joncaire’s presence among them, but that they were masters of their land, and hoped that the French agent would come as often as he pleased; and they begged that the new King of France would take them under his protection.[4] Accordingly, Vaudreuil sent them a present, with a message to the effect that they might plunder such English traders as should come among them.[5]

[3: Journal of Schuyler and Livingston, 1720.]

[4: Vaudreuil au Conseil de Marine, 24 Octobre, 1717.]

[5: Vaudreuil et Bégon au Conseil de Marine, 26 Octobre, 1719.]

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 17 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.