After a march of about three weeks, the brothers reached a hill, or group of hills, apparently west of the Little Missouri, and perhaps a part of the Powder River Range.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 16.

The two Frenchmen crossed over to the camp of these western strangers, among whom they found a chief who spoke, or professed to speak, the language of the mysterious white men, which to the two Frenchmen was unintelligible. Fortunately, he also spoke the language of the Mandans, of which the Frenchmen had learned a little during their stay, and hence were able to gather that the white men in question had beards, and that they prayed to the Master of Life in great houses, built for the purpose, holding books, the leaves of which were like husks of Indian corn, singing together and repeating Jésus, Marie. The chief gave many other particulars, which seemed to show that he had been in contact with Spaniards, — probably those of California; for he described their houses as standing near the great lake, of which the water rises and falls and is not fit to drink. He invited the two Frenchmen to go with him to this strange country, saying that it could be reached before winter, though a wide circuit must be made, to avoid a fierce and dangerous tribe called Snake Indians (Gens du Serpent).

The two Frenchmen crossed over to the camp of these western strangers, among whom they found a chief who spoke, or professed to speak, the language of the mysterious white men, which to the two Frenchmen was unintelligible. Fortunately, he also spoke the language of the Mandans, of which the Frenchmen had learned a little during their stay, and hence were able to gather that the white men in question had beards, and that they prayed to the Master of Life in great houses, built for the purpose, holding books, the leaves of which were like husks of Indian corn, singing together and repeating Jésus, Marie. The chief gave many other particulars, which seemed to show that he had been in contact with Spaniards, — probably those of California; for he described their houses as standing near the great lake, of which the water rises and falls and is not fit to drink. He invited the two Frenchmen to go with him to this strange country, saying that it could be reached before winter, though a wide circuit must be made, to avoid a fierce and dangerous tribe called Snake Indians (Gens du Serpent).

[Journal du Sieur de la Vérendrye, 1740, in Archives de la Marine.]

On hearing this story, La Vérendrye sent his eldest son, Pierre, to pursue the discovery with two men, ordering him to hire guides among the Mandans and make his way to the Western Sea. But no guides were to be found, and in the next summer the young man returned from his bootless errand.

[Mémoire du Sieur de la Vérendrye, joint à sa lettre du 31 Octobre, 1744.]

Undaunted by this failure, Pierre set out again in the next spring, 1742, with his younger brother, the Chevalier de la Vérendrye. Accompanied only by two Canadians, they left Fort La Reine on the twenty-ninth of April, and following, no doubt, the route of the Assiniboin and Mouse River, reached the chief village of the Mandans in about three weeks.

Here they found themselves the welcome guests of this singularly interesting tribe, ruined by the small-pox nearly half a century ago, but preserved to memory by the skilful pencil of the artist Charles Bodmer, and the brush of the painter George Catlin, both of whom saw them at a time when they were little changed in habits and manners since the visit of the brothers La Vérendrye.

[Prince Maximilian spent the winter of 1832-33 near the Mandan villages. His artist, with the instinct of genius, seized the characteristics of the wild life before him, and rendered them with admirable vigor and truth. Catlin spent a considerable time among the Mandans soon after the visit of Prince Maximilian, and had unusual opportunities of studying them. He was an indifferent painter, a shallow observer, and a garrulous and windy writer; yet his enthusiastic industry is beyond praise, and his pictures are invaluable as faithful reflections of aspects of Indian life which are gone forever.

Beauharnois calls the Mandans Blancs Barbus, and says that they have been hitherto unknown. Beauharnois au Ministre, 14 Août, 1739. The name Mantannes, or Mandans, is that given them by the Assiniboins.]

Thus, though the report of the two brothers is too concise and brief, we know what they saw when they entered the central area, or public square, of the village. Around stood the Mandan lodges, looking like round flattened hillocks of earth, forty or fifty feet wide. On examination they proved to be framed of strong posts and poles, covered with a thick matting of intertwined willow-branches, over which was laid a bed of well-compacted clay or earth two or three feet thick. This heavy roof was supported by strong interior posts.[1] The open place which the dwellings enclosed served for games, dances, and the ghastly religious or magical ceremonies practised by the tribe. Among the other structures was the sacred “medicine lodge,” distinguished by three or four tall poles planted before it, each surmounted by an effigy looking much like a scarecrow, and meant as an offering to the spirits.

[1: The Minnetarees and other tribes of the Missouri built their lodges in a similar way.]

If the two travelers had been less sparing of words, they would doubtless have told us that as they entered the village square the flattened earthen domes that surrounded it were thronged with squaws and children, — for this was always the case on occasions of public interest, — and that they were forced to undergo a merciless series of feasts in the lodges of the chiefs. Here, seated by the sunken hearth in the middle, under the large hole in the roof that served both for window and chimney, they could study at their ease the domestic economy of their entertainers. Each lodge held a gens, or family connection, whose beds of raw buffalo hide, stretched on poles, were ranged around the circumference of the building, while by each stood a post on which hung shields, lances, bows, quivers, medicine-bags, and masks formed of the skin of a buffalo’s head, with the horns attached, to be used in the magic buffalo dance.

Every day had its sports to relieve the monotony of savage existence, the game of the stick and the rolling ring, the archery practice of boys, horse-racing on the neighboring prairie, and incessant games of chance; while every evening, in contrast to these gayeties, the long, dismal wail of women rose from the adjacent cemetery, where the dead of the village, sewn fast in buffalo hides, lay on scaffolds above the reach of wolves.

The Mandans did not know the way to the Pacific, but they told the brothers that they expected a speedy visit from a tribe or band called Horse Indians, who could guide them thither. It is impossible to identify this people with any certainty.[2] The two travelers waited for them in vain till after midsummer, and then, as the season was too far advanced for longer delay, they hired two Mandans to conduct them to their customary haunts.

[2: The Cheyennes have a tradition that they were the first tribe of this region to have horses. This may perhaps justify a conjecture that the northern division of this brave and warlike people were the Horse Indians of La Vérendrye; though an Indian tradition, unless backed by well-established facts, can never be accepted as substantial evidence.]

They set out on horseback, their scanty baggage and their stock of presents being no doubt carried by pack-animals. Their general course was west-southwest, with the Black Hills at a distance on their left, and the upper Missouri on their right. The country was a rolling prairie, well covered for the most part with grass, and watered by small alkaline streams creeping towards the Missouri with an opaque, whitish current. Except along the watercourses, there was little or no wood. “I noticed,” says the Chevalier de la Vérendrye, “earths of different colors, blue, green, red, or black, white as chalk, or yellowish like ochre.” This was probably in the “bad lands” of the Little Missouri, where these colored earths form a conspicuous feature in the bare and barren bluffs, carved into fantastic shapes by the storms.

[A similar phenomenon occurs farther west on the face of the perpendicular bluffs that, in one place, border the valley of the river Rosebud.]

For twenty days the travelers saw no human being, so scanty was the population of these plains. Game, however, was abundant. Deer sprang from the tall, reedy grass of the river bottoms; buffalo tramped by in ponderous columns, or dotted the swells of the distant prairie with their grazing thousands; antelope approached, with the curiosity of their species, to gaze at the passing horsemen, then fled like the wind; and as they neared the broken uplands towards the Yellowstone, they saw troops of elk and flocks of mountain-sheep. Sometimes, for miles together, the dry plain was studded thick with the earthen mounds that marked the burrows of the curious marmots, called prairie-dogs, from their squeaking bark. Wolves, white and gray, howled about the camp at night, and their cousin, the coyote, seated in the dusk of evening upright on the grass, with nose turned to the sky, saluted them with a complication of yelpings, as if a score of petulant voices were pouring together from the throat of one small beast.

On the eleventh of August, after a march of about three weeks, the brothers reached a hill, or group of hills, apparently west of the Little Missouri, and perhaps a part of the Powder River Range. It was here that they hoped to find the Horse Indians, but nobody was to be seen. Arming themselves with patience, they built a hut, made fires to attract by the smoke any Indians roaming near, and went every day to the tops of the hills to reconnoiter. At length, on the fourteenth of September, they descried a spire of smoke on the distant prairie.

One of their Mandan guides had left them and gone back to his village. The other, with one of the Frenchmen, went towards the smoke, and found a camp of Indians, whom the journal calls Les Beaux Hommes, and who were probably Crows, or Apsaroka, a tribe remarkable for stature and symmetry, who long claimed that region as their own. They treated the visitors well, and sent for the other Frenchmen to come to their lodges, where they were received with great rejoicing. The remaining Mandan, however, became frightened, — for the Beaux Hommes were enemies of his tribe, — and he soon followed his companion on his solitary march homeward.

The brothers remained twenty-one days in the camp of the Beaux Hommes, much perplexed for want of an interpreter. The tribes of the plains have in common a system of signs by which they communicate with each other, and it is likely that the brothers had learned it from the Sioux or Assiniboins, with whom they had been in familiar intercourse. By this or some other means they made their hosts understand that they wished to find the Horse Indians; and the Beaux Hommes, being soothed by presents, offered some of their young men as guides. They set out on the ninth of October, following a south-southwest course.

[Journal du Voyage fait par le Chevalier de la Vérendrye en 1742. The copy before me is from the original in the Dépôt des Cartes de la Marine. A duplicate, in the Archives des Affaires Étrangères, is printed by Margry. It gives the above date as November 9 instead of October 9. The context shows the latter to be correct.]

In two days they met a band of Indians, called by them the Little Foxes, and on the fifteenth and seventeenth two villages of another unrecognizable horde, named Pioya. From La Vérendrye’s time to our own, this name “villages” has always been given to the encampments of the wandering people of the plains. All these nomadic communities joined them, and they moved together southward, till they reached at last the lodges of the long-sought Horse Indians. They found them in the extremity of distress and terror. Their camp resounded with howls and wailings; and not without cause, for the Snakes, or Shoshones, — a formidable people living farther westward, — had lately destroyed most of their tribe. The Snakes were the terror of that country. The brothers were told that the year before they had destroyed seventeen villages, killing the warriors and old women, and carrying off the young women and children as slaves.

None of the Horse Indians had ever seen the Pacific; but they knew a people called Gens de l’Arc, or Bow Indians, who, as they said, had traded not far from it. To the Bow Indians, therefore, the brothers resolved to go, and by dint of gifts and promises they persuaded their hosts to show them the way. After marching southwestward for several days, they saw the distant prairie covered with the pointed buffalo-skin lodges of a great Indian camp. It was that of the Bow Indians, who may have been one of the bands of the western Sioux, — the predominant race in this region. Few or none of them could ever have seen a white man, and we may imagine their amazement at the arrival of the strangers, who, followed by staring crowds, were conducted to the lodge of the chief. “Thus far,” says La Vérendrye, “we had been well received in all the villages we had passed; but this was nothing compared with the courteous manners of the great chief of the Bow Indians, who, unlike the others, was not self-interested in the least, and who took excellent care of everything belonging to us.”

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 16 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series was called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

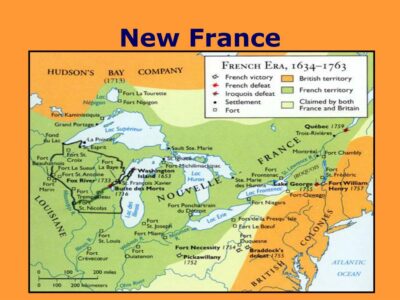

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.