He had explored a vast region hitherto unknown, diverted a great and lucrative fur-trade from the English at Hudson Bay, and secured possession of it by six fortified posts.

Our special project presenting the definitive account of France in Canada by Francis Parkman, one of America’s greatest historians.

Previously in A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2. Continuing Chapter 16.

As his own resources were of the smallest, he took a number of associates on conditions most unfavorable to himself. Among them they raised money enough to begin the enterprise, and on the eighth of June, 1731, La Vérendrye and three of his sons, together with his nephew, La Jemeraye, the Jesuit Messager, and a party of Canadians, set out from Montreal. It was late in August before they reached the great portage of Lake Superior, which led across the height of land separating the waters of that lake from those flowing to Lake Winnipeg. The way was long and difficult. The men, who had perhaps been tampered with, mutinied, and refused to go farther.[1] Some of them, with much ado, consented at last to proceed, and, under the lead of La Jemeraye, made their way by an intricate and broken chain of lakes and streams to Rainy Lake, where they built a fort and called it Fort St. Pierre. La Vérendrye was forced to winter with the rest of the party at the river Kaministiguia, not far from the great portage. Here months were lost, during which a crew of useless mutineers had to be fed and paid; and it was not till the next June that he could get them again into motion towards Lake Winnipeg.

As his own resources were of the smallest, he took a number of associates on conditions most unfavorable to himself. Among them they raised money enough to begin the enterprise, and on the eighth of June, 1731, La Vérendrye and three of his sons, together with his nephew, La Jemeraye, the Jesuit Messager, and a party of Canadians, set out from Montreal. It was late in August before they reached the great portage of Lake Superior, which led across the height of land separating the waters of that lake from those flowing to Lake Winnipeg. The way was long and difficult. The men, who had perhaps been tampered with, mutinied, and refused to go farther.[1] Some of them, with much ado, consented at last to proceed, and, under the lead of La Jemeraye, made their way by an intricate and broken chain of lakes and streams to Rainy Lake, where they built a fort and called it Fort St. Pierre. La Vérendrye was forced to winter with the rest of the party at the river Kaministiguia, not far from the great portage. Here months were lost, during which a crew of useless mutineers had to be fed and paid; and it was not till the next June that he could get them again into motion towards Lake Winnipeg.

[1: Mémoire du Sieur de la Vérendrye du Sujet des Établissements pour parvenir à la Découverte de la Mer de l’Ouest, in Margry, vi. 585.]

This ominous beginning was followed by a train of disasters. His associates abandoned him; the merchants on whom he depended for supplies would not send them, and he found himself, in his own words, “destitute of everything.” His nephew, La Jemeraye, died. The Jesuit Auneau, bent on returning to Michilimackinac, set out with La Vérendrye’s eldest son and a party of twenty Canadians. A few days later, they were all found on an island in the Lake of the Woods, murdered and mangled by the Sioux.[2] The Assiniboins and Cristineaux, mortal foes of that fierce people, offered to join the French and avenge the butchery; but a war with the Sioux would have ruined La Vérendrye’s plans of discovery, and exposed to torture and death the French traders in their country. Therefore he restrained himself and declined the proffered aid, at the risk of incurring the contempt of those who offered it.

[2: Beauharnois au Ministre, 14 Octobre, 1736; Relation du Massacre au Lac des Bois, en Juin, 1736; Journal de la Vérendrye, joint à la lettre de M. de Beauharnois du — Octobre, 1737.]

Beauharnois twice appealed to the court to give La Vérendrye some little aid, urging that he was at the end of his resources, and that a grant of thirty thousand francs, or six thousand dollars, would enable him to find a way to the Pacific. All help was refused, but La Vérendrye was told that he might let out his forts to other traders, and so raise means to pursue the discovery.

In 1740 he went for the third time to Montreal, where, instead of aid, he found a lawsuit. “In spite,” he says, “of the derangement of my affairs, the envy and jealousy of various persons impelled them to write letters to the court insinuating that I thought of nothing but making my fortune. If more than forty thousand livres of debt which I have on my shoulders are an advantage, then I can flatter myself that I am very rich. In all my misfortunes, I have the consolation of seeing that M. de Beauharnois enters into my views, recognizes the uprightness of my intentions, and does me justice in spite of opposition.”

[Mémoire du Sieur de la Vérendrye au Sujet des Établissements pour parvenir à la Découverte de la Mer de l’Ouest.]

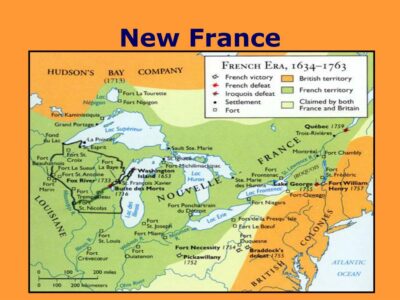

Meanwhile, under all his difficulties, he had explored a vast region hitherto unknown, diverted a great and lucrative fur-trade from the English at Hudson Bay, and secured possession of it by six fortified posts, — Fort St. Pierre, on Rainy Lake; Fort St. Charles, on the Lake of the Woods; Fort Maurepas, at the mouth of the river Winnipeg; Fort Bourbon, on the eastern side of Lake Winnipeg; Fort La Reine, on the Assiniboin; Fort Dauphin, on Lake Manitoba. Besides these he built another post, called Fort Rouge, on the site of the city of Winnipeg; and, some time after, another, at the mouth of the river Poskoiac, or Saskatchewan, neither of which, however, was long occupied. These various forts were only stockade works flanked with blockhouses; but the difficulty of building and maintaining them in this remote wilderness was incalculable.

[Mémoire en abrégé de la Carte qui représente les Établissements faits par le Sieur de la Vérendrye et ses Enfants (Margry, vi. 616); Carte des Nouvelles Découvertes dans l’Ouest du Canada dressée sur les Mémoires du M^r. de la Vérendrye et donnée au Dépôt de la Marine par M. de la Galissonnière, 1750; Bellin, Remarques sur la Carte de l’Amérique, 1755; Bougainville, Mémoire sur l’État de la Nouvelle France, 1757.

Most of La Vérendrye’s forts were standing during the Seven Years’ War, and were known collectively as Postes de la Mer de l’Ouest.]

He had inquired on all sides for the Pacific. The Assiniboins could tell him nothing. Nor could any information be expected from them, since their relatives and mortal enemies, the Sioux, barred their way to the West. The Cristineaux were equally ignorant; but they supplied the place of knowledge by invention, and drew maps, some of which seem to have been made with no other intention than that of amusing themselves by imposing on the inquirer. They also declared that some of their number had gone down a river called White River, or River of the West, where they found a plant that shed drops like blood and saw serpents of prodigious size. They said further that on the lower part of this river were walled towns, where dwelt white men who had knives,

hatchets, and cloth, but no firearms.

[Journal de la Vérendrye joint à la Lettre de M. de Beauharnois du — Octobre, 1737.]

Both Assiniboins and Cristineaux declared that there was a distant tribe on the Missouri, called Mantannes (Mandans), who knew the way to the Western Sea, and would guide him to it. Lured by this assurance, and feeling that he had sufficiently secured his position to enable him to begin his western exploration, La Vérendrye left Fort La Reine in October, 1738, with twenty men, and pushed up the river Assiniboin till its rapids and shallows threatened his bark canoes with destruction. Then, with a band of Assiniboin Indians who had joined him, he struck across the prairie for the Mandans, his Indian companions hunting buffalo on the way. They approached the first Mandan village on the afternoon of the third of December, displaying a French flag and firing three volleys as a salute. The whole population poured out to see the marvelous visitors, who were conducted through the staring crowd to the lodge of the principal chief, — a capacious structure so thronged with the naked and greasy savages that the Frenchmen were half smothered. What was worse, they lost the bag that held all their presents for the Mandans, which was snatched away in the confusion, and hidden in one of the caches, called cellars by La Vérendrye, of which the place was full. The chief seemed much discomposed at this mishap and explained it by saying that there were many rascals in the village. The loss was serious, since without the presents nothing could be done. Nor was this all; for in the morning La Vérendrye missed his interpreter and was told that he had fallen in love with an Assiniboin girl and gone off in pursuit of her. The French were now without any means of communicating with the Mandans, from whom, however, before the disappearance of the interpreter, they had already received a variety of questionable information, chiefly touching white men cased in iron who were said to live on the river below at the distance of a whole summer’s journey. As they were impervious to arrows, — so the story ran, — it was necessary to shoot their horses, after which, being too heavy to run, they were easily caught. This was probably suggested by the armor of the Spaniards, who had more than once made incursions as far as the lower Missouri; but the narrators drew on their imagination for various additional particulars.

The Mandans seem to have much declined in numbers during the century that followed this visit of La Vérendrye. He says that they had six villages on or near the Missouri, of which the one seen by him was the smallest, though he thinks that it contained a hundred and thirty houses.[3] As each of these large structures held a number of families, the population must have been considerable. Yet when Prince Maximilian visited the Mandans in 1833, he found only two villages, containing jointly two hundred and forty warriors and a total population of about a thousand souls. Without having seen the statements of La Vérendrye, he speaks of the population as greatly reduced by wars and the small-pox, — a disease which a few years later nearly exterminated the tribe.[4]

[3: Journal de La Vérendrye, 1738, 1739. This journal, which is ill-written and sometimes obscure, is printed in Brymner, Report on Canadian Archives, 1889.]

[4: Le Prince Maximilien de Wied-Neuwied, Voyage dans l’Intérieur de l’Amérique du Nord, ii. 371, 372 (Paris, 1843). When Captains Lewis and Clark visited the Mandans in 1804, they found them in two villages, with about three hundred and fifty warriors. They report that, about forty years before, they lived in nine villages, the ruins of which the explorers saw about eighty miles below the two villages then occupied by the tribe. The Mandans had moved up the river in consequence of the persecutions of the Sioux and the small-pox, which had made great havoc among them. Expedition of Lewis and Clark, i. 129 (ed. Philadelphia, 1814). These nine villages seem to have been above Cannon-ball River, a tributary of the Missouri.]

La Vérendrye represents the six villages as surrounded with ditches and stockades, flanked by a sort of bastion, — defences which, he says, had nothing savage in their construction. In later times the fortifications were of a much ruder kind, though Maximilian represents them as having pointed salients to serve as bastions. La Vérendrye mentions some peculiar customs of the Mandans which answer exactly to those described by more recent observers.

He had intended to winter with the tribe; but the loss of the presents and the interpreter made it useless to stay, and, leaving two men in the village to learn the language, he began his return to Fort La Reine. “I was very ill,” he writes, “but hoped to get better on the way. The reverse was the case, for it was the depth of winter. It would be impossible to suffer more than I did. It seemed that nothing but death could release us from such miseries.” He reached Fort La Reine on the eleventh of February, 1739.

His iron constitution seems to have been severely shaken; but he had sons worthy of their father. The two men left among the Mandans appeared at Fort La Reine in September. They reported that they had been well treated, and that their hosts had parted from them with regret. They also declared that at the end of spring several Indian tribes, all well supplied with horses, had come, as was their yearly custom, to the Mandan villages to barter embroidered buffalo hides and other skins for corn and beans; that they had encamped, to the number of two hundred lodges, on the farther side of the Missouri, and that among them was a band said to have come from a distant country towards the sunset, where there were white men who lived in houses built of bricks and stones.

From A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 2, Chapter 16 by Francis Parkman

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Volume 6 of Parkman’s History of France in North America titled “A Half-Century of Conflict” was itself published in two volumes. This means that “Volume 6” (consistent with how past books published on this website were called) must be called “Part 6”, instead – to avoid confusion. This book is Volume 2 of “A Half-Century of Conflict”. The previous book in the series will be called “Part 6, A Half-Century of Conflict, Volume 1”.

The below is from Francis Parkman’s Preface to this book.

This book, forming Part VI. of the series called France and England in North America, fills the gap between Part V., “Count Frontenac,” and Part VII., “Montcalm and Wolfe;” so that the series now forms a continuous history of the efforts of France to occupy and control this continent.

In the present volumes the nature of the subject does not permit an unbroken thread of narrative, and the unity of the book lies in its being throughout, in one form or another, an illustration of the singularly contrasted characters and methods of the rival claimants to North America.

Like the rest of the series, this work is founded on original documents. The statements of secondary writers have been accepted only when found to conform to the evidence of contemporaries, whose writings have been sifted and collated with the greatest care. As extremists on each side have charged me with favoring the other, I hope I have been unfair to neither.

The manuscript material collected for the preparation of the series now complete forms about seventy volumes, most of them folios. These have been given by me from time to time to the Massachusetts Historical Society, in whose library they now are, open to the examination of those interested in the subjects of which they treat. The collection was begun forty-five years ago, and its formation has been exceedingly slow, having been retarded by difficulties which seemed insurmountable, and for years were so in fact. Hence the completion of the series has required twice the time that would have sufficed under less unfavorable conditions.

BOSTON, March 26, 1892

MORE INFORMATION

TEXT LIBRARY

- Here’s a free download of this book from Gutenberg.

- Overview of these conflicts.

- Military of New France.

- French Explorers of North America

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Other books of this series here at History Moments

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.