This series has five easy 5-minute installments. This first installment: Introductory

Reflections.

Introduction

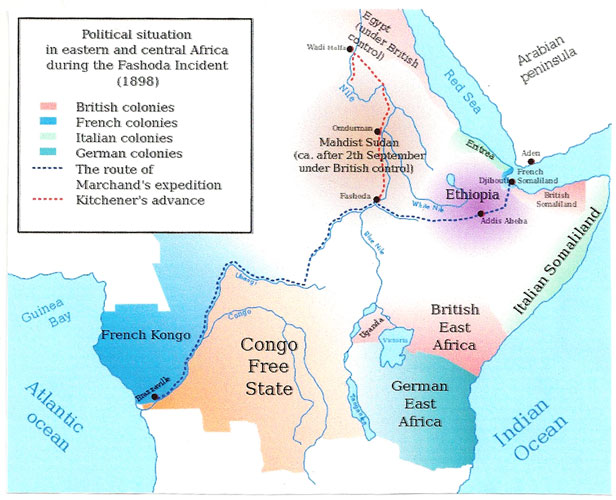

The scramble of the nations of Europe for land in Africa was already well on by the time of this incident. The two nations led the scramble were France and Great Britain. With the exception of the Crimean War (an alliance based on having a common enemy), the two nations had a adversarial posture which went back centuries. When two forces from these two countries met in the depths of the disputed continent, this incident led to a diplomatic crisis. From this crisis, a adversaries became friends, and the African natives were doomed to the rewards and the degradation on colonial occupation.

This selection is from The River War by Winston S. Churchill published in 1899. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Winston S. Churchill (1874-1965) was the great Prime Minister and winner of the Nobel Prize in literature. He was the great supporter of the British Empire.

Time: September 18, 1898

Place: Fashoda on the White Nile, in Sudan

The long succession of events, of which I have attempted to give some account,* has not hitherto affected to any great extent other countries than those which are drained by the Nile. But this chapter demands a wider view, since it must describe an incident which might easily have convulsed Europe, and from which far-reaching consequences have arisen. It is unlikely that the world will ever learn the details of the subtle scheme of which the Marchand Mission was a famous part. We may say with certainty that the French Government did not intend a small expedition, at great peril to itself, to seize and hold an obscure swamp on the Upper Nile. But it is not possible to define the other arrangements. What part the Abyssinians were expected to play, what services had been rendered them and what inducements they were offered, what attitude was to be adopted to the Khalifa, what use was to be made of the local tribes: all this is veiled in the mystery of intrigue. It is well known that for several years France, at some cost to herself and at a greater cost to Italy, had courted the friendship of Abyssinia, and that the weapons by which the Italians were defeated at Adowa had been mainly supplied through French channels. A small quick-firing gun of continental manufacture and of recent make which was found in the possession of the Khalifa seems to point to the existence or contemplation of similar relations with the Dervishes. But how far these operations were designed to assist the Marchand Mission is known only to those who initiated them, and to a few others who have so far kept their own counsel.

[* The campaign up the Nile River from Egypt to Khartoum. ED]

The undisputed facts are few. Towards the end of 1896 a French expedition was dispatched from the Atlantic into the heart of Africa under the command of Major Marchand. The re-occupation of Dongola was then practically complete, and the British Government were earnestly considering the desirability of a further advance. In the beginning of 1897 a British expedition, under Colonel Macdonald, and comprising a dozen carefully selected officers, set out from England to Uganda, landed at Mombassa, and struck inland. The misfortunes which fell upon this enterprise are beyond the scope of this account, and I shall not dwell upon the local jealousies and disputes which marred it. It is sufficient to observe that Colonel Macdonald was provided with Soudanese troops who were practically in a state of mutiny and actually mutinied two days after he assumed command. The officers were compelled to fight for their lives. Several were killed. A year was consumed in suppressing the mutiny and the revolt which arose out of it. If the object of the expedition was to reach the Upper Nile, it was soon obviously unattainable, and the Government were glad to employ the officers in making geographical surveys.

At the beginning of 1898 it was clear to those who, with the fullest information, directed the foreign policy of Great Britain that no results affecting the situation in the Soudan could be expected from the Macdonald Expedition. The advance to Khartoum and the reconquest of the lost provinces had been irrevocably undertaken. An Anglo-Egyptian force was already concentrating at Berber. Lastly, the Marchand Mission was known to be moving towards the Upper Nile, and it was a probable contingency that it would arrive at its destination within a few months. It was therefore evident that the line of advance of the powerful army moving south from the Mediterranean and of the tiny expedition moving east from the Atlantic must intersect before the end of the year, and that intersection would involve a collision between the Powers of Great Britain and France.

I do not pretend to any special information not hitherto given to the public in this further matter, but the reader may consider for himself whether the conciliatory policy which Lord Salisbury pursued towards Russia in China at this time — a policy which excited hostile criticism in England –was designed to influence the impending conflict on the Upper Nile and make it certain, or at least likely, that when Great Britain and France should be placed in direct opposition, France should find herself alone.

With these introductory reflections we may return to the theatre of the war.

On the 7th of September, five days after the battle and capture of Omdurman, the Tewfikia, a small Dervish steamer — one of those formerly used by General Gordon — came drifting and paddling down the river. Her Arab crew soon perceived by the Egyptian flags which were hoisted on the principal buildings, and by the battered condition of the Mahdi’s Tomb, that all was not well in the city; and then, drifting a little further, they found themselves surrounded by the white gunboats of the ‘Turks,’ and so incontinently surrendered. The story they told their captors was a strange one. They had left Omdurman a month earlier, in company with the steamer Safia, carrying a force of 500 men, with the Khalifa’s orders to go up the White Nile and collect grain. For some time all had been well, but on approaching the old Government station of Fashoda they had been fired on by black troops commanded by white officers under a strange flag — and fired on with such effect that they had lost some forty men killed and wounded. Doubting who these formidable enemies might be, the foraging expedition had turned back, and the Emir in command, having disembarked and formed a camp at a place on the east bank called Reng, had sent the Tewfikia back to ask the Khalifa for instructions and reinforcements. The story was carried to the Sirdar and ran like wildfire through the camp. Many officers made their way to the river, where the steamer lay, to test for themselves the truth of the report. The woodwork of the hull was marked with many newly made holes and cutting into these with their penknives the officers extracted bullets—not the roughly cast leaden balls, the bits of telegraph wire, or old iron which savages use, but the conical nickel-covered bullets of small-bore rifles such as are fired by civilized forces alone. Here was positive proof. A European Power was on the Upper Nile: which? Some said it was the Belgians from the Congo; some that an Italian expedition had arrived; others thought that the strangers were French; others, again, believed in the Foreign Office — it was a British expedition, after all. The Arab crew were cross-examined as to the flag they had seen. Their replies were inconclusive. It had bright colors, they declared; but what those colors were and what their arrangement might be they could not tell; they were poor men, and God was very great.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.