Introduction

What was it like to be a child in school in colonial days? This story (The Old Fashion School) by one of America’s greatest writers draws from his own life experience.

This selection is from True Stories of History and Biogrphy by Nathaniel Hawthorne published in 1850. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864) was the writer and novelist of The Scarlet Letter.

And here Grandfather endeavored to give his auditors an idea how matters were managed in schools above a hundred years ago. As this will probably be an interesting subject to our readers, we shall make a separate sketch of it, and call it

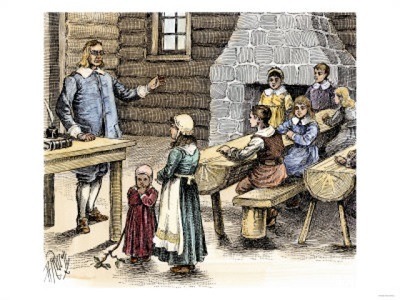

Now imagine yourselves, my children, in Master Ezekiel Cheever’s school-room. It is a large, dingy room, with a sanded floor, and is lighted by windows that turn on hinges, and have little diamond shaped panes of glass. The scholars sit on long benches, with desks before them. At one end of the room is a great fire-place, so very spacious, that there is room enough for three or four boys to stand in each of the chimney corners. This was the good old fashion of fire-places, when there was wood enough in the forests to keep people warm, without their digging into the bowels of the earth for coal.

It is a winter’s day when we take our peep into the school-room. See what great logs of wood have been rolled into the fire-place, and what a broad, bright blaze goes leaping up the chimney! And every few moments, a vast cloud of smoke is puffed into the room, which sails slowly over the heads of the scholars, until it gradually settles upon the walls and ceiling. They are blackened with the smoke of many years already.

Next, look at our old historic chair! It is placed, you perceive, in the most comfortable part of the room, where the generous glow of the fire is sufficiently felt, without being too intensely hot. How stately the old chair looks, as if it remembered its many famous occupants, but yet were conscious that a greater man is sitting in it now! Do you see the venerable school-master, severe in aspect, with a black scull-cap on his head, like an ancient Puritan, and the snow of his white beard drifting down to his very girdle? What boy would dare to play, or whisper, or even glance aside from his book, while Master Cheever is on the look-out, behind his spectacles! For such offenders, if any such there be, a rod of birch is hanging over the fireplace, and a heavy ferule lies on the master’s desk.

And now school is begun. What a murmur of multitudinous tongues, like the whispering leaves of a wind-stirred oak, as the scholars con over their various tasks! Buz, buz, buz! Amid just such a murmur has Master Cheever spent above sixty years: and long habit has made it as pleasant to him as the hum of a bee-hive, when the insects are busy in the sunshine.

Now a class in Latin is called to recite. Forth steps a row of queer-looking little fellows, wearing square-skirted coats, and small clothes, with buttons at the knee. They look like so many grandfathers in their second childhood. These lads are to be sent to Cambridge, and educated for the learned professions. Old Master Cheever has lived so long, and seen so many generations of school-boys grow up to be men, that now he can almost prophesy what sort of a man each boy will be. One urchin shall hereafter be a doctor, and administer pills and potions, and stalk gravely through life, perfumed with assaf[oe]tida. Another shall wrangle at the bar, and fight his way to wealth and honors, and in his declining age, shall be a worshipful member of his Majesty’s council. A third — and he is the Master’s favorite – shall be a worthy successor to the old Puritan ministers, now in their graves; he shall preach with great unction and effect, and leave volumes of sermons, in print and manuscript, for the benefit of future generations.

But, as they are merely school-boys now, their business is to construe Virgil. Poor Virgil, whose verses, which he took so much pains to polish, have been mis-scanned, and mis-parsed, and mis-interpreted, by so many generations of idle school-boys! There, sit down, ye Latinists. Two or three of you, I fear, are doomed to feel the master’s ferule.

Next comes a class in Arithmetic. These boys are to be the merchants, shop-keepers, and mechanics, of a future period. Hitherto, they have traded only in marbles and apples. Hereafter, some will send vessels to England for broadcloths and all sorts of manufactured wares, and to the West Indies for sugar, and rum, and coffee. Others will stand behind counters, and measure tape, and ribbon, and cambric, by the yard. Others will upheave the blacksmith’s hammer, or drive the plane over the carpenter’s bench, or take the lapstone and the awl, and learn the trade of shoe-making. Many will follow the sea, and become bold, rough sea-captains.

This class of boys, in short, must supply the world with those active, skillful hands, and clear, sagacious heads, without which the affairs of life would be thrown into confusion, by the theories of studious and visionary men. Wherefore, teach them their multiplication table, good Master Cheever, and whip them well, when they deserve it; for much of the country’s welfare depends on these boys!

But, alas! while we have been thinking of other matters, Master Cheever’s watchful eye has caught two boys at play. Now we shall see awful times! The two malefactors are summoned before the master’s chair, wherein he sits, with the terror of a judge upon his brow. Our old chair is now a judgment-seat. Ah, Master Cheever has taken down that terrible birch-rod! Short is the trial — the sentence quickly passed — and now the judge prepares to execute it in person. Thwack! thwack! thwack! In those good old times, a school-master’s blows were well laid on.

See! the birch-rod has lost several of its twigs and will hardly serve for another execution. Mercy on us, what a bellowing the urchins make! My ears are almost deafened, though the clamor comes through the far length of a hundred and fifty years. There, go to your seats, poor boys; and do not cry, sweet little Alice; for they have ceased to feel the pain, a long time since.

And thus, the forenoon passes away. Now it is twelve o’clock. The master looks at his great silver watch, and then with tiresome deliberation, puts the ferule into his desk. The little multitude await the word of dismissal, with almost irrepressible impatience.

“You are dismissed,” says Master Cheever.

The boys retire, treading softly until they have passed the threshold; but, fairly out of the school-room, lo, what a joyous shout!—what a scampering and trampling of feet!—what a sense of recovered freedom, expressed in the merry uproar of all their voices! What care they for the ferule and birch-rod now? Were boys created merely to study Latin and Arithmetic? No; the better purposes of their being are to sport, to leap, to run, to shout, to slide upon the ice, to snow-ball!

Happy boys! Enjoy your play-time now, and come again to study, and to feel the birch-rod and the ferule, to-morrow; not till to-morrow, for to-day is Thursday-lecture; and ever since the settlement of Massachusetts, there has been no school on Thursday afternoons. Therefore, sport, boys, while you may; for the morrow cometh, with the birch-rod and the ferule; and after that, another Morrow, with troubles of its own.

Now the master has set everything to rights and is ready to go home to dinner. Yet he goes reluctantly. The old man has spent so much of his life in the smoky, noisy, buzzing school-room, that, when he has a holiday, he feels as if his place were lost, and himself a stranger in the world. But, forth he goes; and there stands our old chair, vacant and solitary, till good Master Cheever resumes his seat in it to-morrow morning.

“Grandfather,” said Charley, “I wonder whether the boys did not use to upset the old chair, when the school-master was out?”

“There is a tradition,” replied Grandfather, “that one of its arms was dislocated, in some such manner. But I cannot believe that any school-boy would behave so naughtily.”

As it was now later than little Alice’s usual bedtime, Grandfather broke off his narrative, promising to talk more about Master Cheever and his scholars, some other evening.

More information here and here and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.