Their position may rather be compared with the conquistas of the Spaniards on the Pyrenean peninsula, isolated districts destined to form the basis of a future conquest.

Continuing The Earliest Jews,

our selection from Universal History: The Oldest Historical of Nations and Greece by Leopold von Ranke published in 1884. The selection is presented in six easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Earliest Jews.

The march of the tribes was at the same time arranged on military principles. The tribe of Levi was near the tabernacle, in the center; the others were ranged according to the points of the compass, Judah towards the east, Reuben towards the south, Ephraim towards the west, Dan towards the north. On the march the two first preceded, the rest followed the tabernacle, all under their banners with the ensigns of their tribes. It was a host of families in migration, a single caste, all alike warriors ; the tribe set apart for the service of the sanctuary had no precedence.

The march of the tribes was at the same time arranged on military principles. The tribe of Levi was near the tabernacle, in the center; the others were ranged according to the points of the compass, Judah towards the east, Reuben towards the south, Ephraim towards the west, Dan towards the north. On the march the two first preceded, the rest followed the tabernacle, all under their banners with the ensigns of their tribes. It was a host of families in migration, a single caste, all alike warriors ; the tribe set apart for the service of the sanctuary had no precedence.

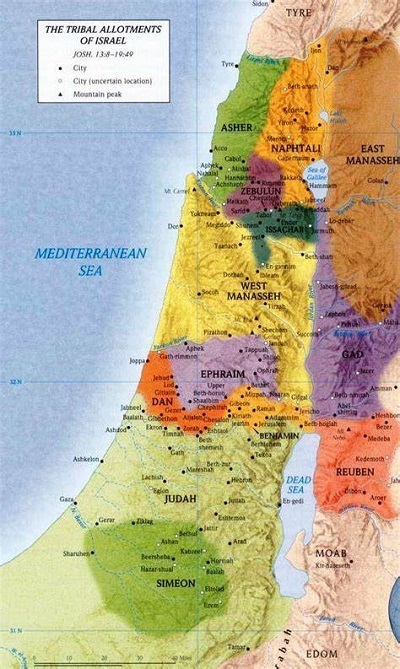

Upon the occupation of the country the sanctuary remained established at Shiloh, the site of which is still recognized by the ruins of its buildings.* The ark of the covenant was at first entrusted to the tribe of Ephraim, which extended northwards over the mountain range which bears its name, without however becoming completely master of the province assigned to it. Gezer, for example, which we find later on as a well-regulated kingdom of small extent, remained Canaanite. Joshua was of the tribe of Ephraim. Sychem seems to have been the chief seat of the secular power. It was the place purchased by Jacob, where the household gods of Laban were buried and to which the bones of Joseph were brought. At a later time it was the center of the northern kingdom. North of Sychem was settled the half-tribe of Manasseh, with an admixture, however, of Ephraimites, and inclosing within its borders five Canaanite towns. Benjamin adjoined Ephraim to the south, a territory the small extent of which was, as Josephus tells us, compensated by its great fertility. Here was situated Jebus, the Jerusalem of a later date, which the Benjamites in vain attempted to conquer. Next in power to Ephraim comes the tribe of Judah, whose portion was upon the southern mountain-range, the abode of the most warlike of the hostile nations, where the struggle continued later than elsewhere. Judah could only occupy the hill country, not the plains, the inhabitants of which used chariots of iron. Simeon I and Dan were under the protection of Judah. An especially bold and enterprising character is ascribed to the tribe of Dan. But, like Judah, it could only obtain possession of the hill country, beyond which for a considerable period it did not venture. To the north of Ephraim were settled the tribes of Issachar and Naphtali, with Zebulon and Asher extending along the western bank of the Jordan. But of Naphtali it is said, “He dwelt among the Canaanites.” Zebulon had two Canaanite towns within its territories. The province of Asher was a narrow strip on the coast of the Phoenician Sea; the task of conquering Sidon, which properly fell to it, it could never dream of attempting, and six towns remained unconquered within its province. Reuben, Gad,and the half- tribe of Manasseh dwelt east of the Jordanina region of forests and pasture lands.

[* Now Seilun, separated by small wadys from the neighboring mountains, rand, although commanded by these heights, a defensible position to a certain |i extent (Robinson, iii. 304).]

The appearance of the Israelites upon the scene of history has been compared with that of the Arabs under Mohammed, and the identity of religious and national feeling in both cases establishes a certain analogy between them. But the distinction is this: that the Arabs being in contact with great kingdoms, and themselves far more powerful than the Israelites, were able to meditate the conquest of the world. The Israelites at first only sought a dwelling-place, for which they had to struggle with kingdoms of small area but considerable vitality. Their position may rather be compared with the conquistas of the Spaniards on the Pyrenean peninsula, isolated districts destined to form the basis of a future conquest.

The Israelites occupied the mountain regions, as the Amorites had done before them; but, like the Amorites, they encountered a vigorous and energetic resistance. First of all, the kindred populations of the Ammonites and Moabites, who thought themselves encroached on by the Israelites, rose against them; then the Midianites, themselves also inhabitants of the desert, invaded, though already once conquered by Israel, the districts occupied by the latter. A powerful prince made his appearance from Mesopotamia and ruled a great part of these districts and populations for some time. On the sea-coast we find the Philistines settle in five cities, each of which obeys its own king, but which formed together one community with a peculiar religious character. Against these assaults, which arc, however, nothing but the reaction against their earlier campaigns, the Israelites had to maintain themselves. The worship of Baal, with which the Egyptians had already contended, maintained its ground with a vigor which the struggle itself intensified and perpetuated, and was often, as the Book of Judges complains, a dangerous rival to the God whose name Israel professed. Against it the warlike tribes found their best weapon in adhesion to the god of their fathers. The leaders who kept them firm in this resolve appear under the name shophetim, a term explained to mean ‘champions of national right’. In the book dedicated to their exploits, the Book of Judges, some of the most distinguished among them are portrayed with some natural admixture of myth, but with clearly marked lineaments.

We read of whole decades of peace, then of disturbance raised by foreign powers. At one time princes whose dominions are of large extent attempt to impose an oppressive bondage; at another, neighboring races with ancient ties of affinity push far into the heart of the country and once more occupy the City of Palms, the ancient Jericho. At times also the native inhabitants, once vanquished, renew their league. Then great men, or sometimes women, come forward to decide the issue by force or stratagem. The traditional account, always perfectly honest, never refuses its grateful praise to deliverances effected by actions which would otherwise excite abhorrence. Sometimes we have men who execute deeds such as that perpetrated many centuries afterwards by Clement upon Henry III, or women who avail themselves of the exhaustion of a hostile general to put him to a horrible death by piercing his temples. We recognize an imperiled nationality, ready to employ any means, whatever their character, to save its existence and its religion.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.