That which modern states call their constitution is but the development of this idea, this need of security for life and property.

Continuing The Earliest Jews,

our selection from Universal History: The Oldest Historical of Nations and Greece by Leopold von Ranke published in 1884. The selection is presented in six easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The Earliest Jews.

Thus, under the immediate protection of God, individual life enjoys those rights and immunities which are the foundation of all civil order. That which modern states call their constitution is but the development of this idea, this need of security for life and property. The Mosaic polity involves an opposition to kingship and its claim to be an emanation from the Deity. The contrast with Egypt is here most deeply marked. No more noble inauguration of the first principles of conduct in human society could have been conceived. Egypt receives additional importance from the fact that her tyranny developed in the emigrant tribes a character and customs in direct contrast to her own. No materials for a history of the human race could have been found in the unbroken continuity of a national nature worship. The first solid foundation for this is laid in the revolt against nature worship—in other words, in monotheism. On this principle is built a civil society which is alien to every abuse of power.

Thus, under the immediate protection of God, individual life enjoys those rights and immunities which are the foundation of all civil order. That which modern states call their constitution is but the development of this idea, this need of security for life and property. The Mosaic polity involves an opposition to kingship and its claim to be an emanation from the Deity. The contrast with Egypt is here most deeply marked. No more noble inauguration of the first principles of conduct in human society could have been conceived. Egypt receives additional importance from the fact that her tyranny developed in the emigrant tribes a character and customs in direct contrast to her own. No materials for a history of the human race could have been found in the unbroken continuity of a national nature worship. The first solid foundation for this is laid in the revolt against nature worship—in other words, in monotheism. On this principle is built a civil society which is alien to every abuse of power.

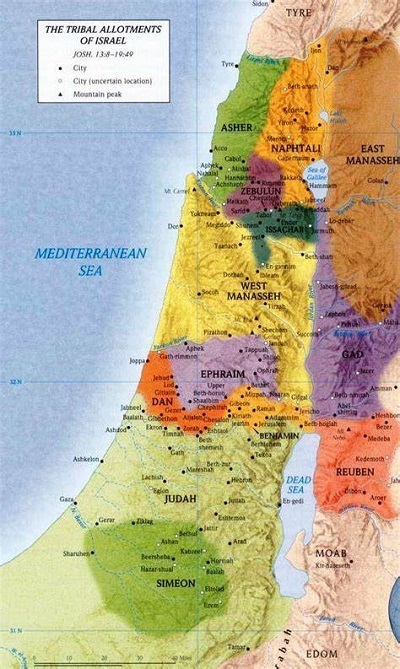

We have thus three great forms of religious worship appearing side by side—the local religion of the Egyptians, the universal nature worship of Baal, and the intellectual Godhead of Jehovah. Like the others, the worship of Jehovah required, and in fact possessed, a national basis. But that basis was supplied by a nation which had scarcely escaped from the bondage of the Egyptians, and which was neglected and unrecognized by the rest of the world. Moses had a continual struggle to maintain with the obstinacy of the multitude, who began to regret Egypt after their departure. It was his achievement that the nation, so feeble at the time of its escape from Egypt, developed after a series of years, long indeed, but not too long for such a result, into a genuine military power, well inured to arms. Yet the first generation had to die out before the Israelites could entertain the hope of acquiring a territory of their own. A claim was suggested by the sojourn of the patriarchs in the land of Canaan during which they had obtained possessions of their own. Moses himself led them to make the claim. This implies no hostility to Egypt. The direction taken was in reality the same as that adopted by the Pharaohs, who failed, however, to reach the goal. In the endeavor to picture to ourselves this struggle we are embarrassed rather than aided by the religious coloring of the narrative. The Most High God, the Creator of the world, was now considered as the national God of the Hebrews, and justly so; for without the Hebrews the worship of Jehovah would have had no place in the world. The war of the Israelites Is represented as the war of Jehovah. The tradition is interwoven with miracles. The aged seer on the enemy’s side is compelled, against his will, to bless Israel, instead of cursing him; the Israelites cross the Jordan dry-shod; an angel of the Lord appears to the captain of the host in the character of a constant though invisible ally; the walls of Jericho fall at the blast of trumpets. A disaster soon afterwards experienced is traced to the fact that a portion of the spoil—gold, silver, copper, and iron — destined for Jehovah has been kept back and buried by one who has broken his oath. The crime is terribly avenged upon the culprit and his whole house, and thereupon one victory follows after another. In the decisive battle with the Amorites, Jehovah prolongs the day at the prayer of the captain of the host. The conquest is regarded as a victory of Jehovah Himself, whose name would otherwise have once more been effaced.

Besides its religious aspect, the event has another and a purely human side, which the historical inquirer, whose business it is to explain events by human motives, is bound to bring into prominence. It is especially to be noticed that the condition of the land of Canaan as depicted in the Book of Joshua corresponds in the main to the statements respecting it in the Egyptian inscriptions. The country was occupied by a number of independent tribes, under princes who called themselves kings. The necessity of combined resistance to the Egyptian invasion united them for a time; but the danger was no sooner over than they relapsed into their former independence. They were compelled, however, to make a combined effort against Israel, who, though formerly unable to maintain his position amongst them, now returned in a later generation to take possession of his old abode -— much as the Heracleidae did at a later date in Peloponnesus, though, as we shall see, with some essential difference. The Israelite tribes had developed into a brave and numerous confederacy of warriors, united and inspired by the idea of their God, whom they formerly worshipped in Canaan, and who had brought them out of Egypt. Even under Moses they were strong enough to seek an encounter with one of the most powerful tribes upon its own soil. This was the tribe of the Amorites, already mentioned also in connection with the struggle with Egypt.

The immediate occasion for this attack was found by Moses in the division between the Amorites and Moabites, the latter of whom claimed a nearer tribal relationship to the Hebrews than the former. The Amorite domain consisted of the two petty kingdoms of Heshbon and Bashan. In the language of an ancient lyric poem,

fire had gone forth from Heshbon and had wasted Moab;”

in other words, Moab had been embroiled in a war with the Amorites, in which he had been defeated. In this contest Moses interfered. The King of Heshbon, who marched with his whole people to encounter him, suffered a defeat. Og, King of Bashan, bestirred himself too late; he also was conquered. A tradition found in Josephus affirms that the invading forces from the desert owed their superiority over their enemies to the use of slings. The victory was followed by the sacking of the towns and the occupation of the country. Those tribes were treated with especial severity which had anciently been in league with Israel, such as the Midianites. Moab himself was already in dread of Israel. Thus, Moses subdued the country beyond the Jordan, and formed a plan according to which the region which he claimed for the tribes was to be divided amongst them.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.