What would be the extent and effects of such a nuclear chain reaction, or of the hazards of the resulting blast and radiation?

Continuing The First Atomic Bomb,

our selection from Project Trinity 1945-1946 by Carl Maag and by Steve Rohrer published in 1982. The selection is presented in nine installments for 5-minute daily reading. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The First Atomic Bomb.

Time: July 16, 1945

Place: Old McDonald Ranch House, New Mexico

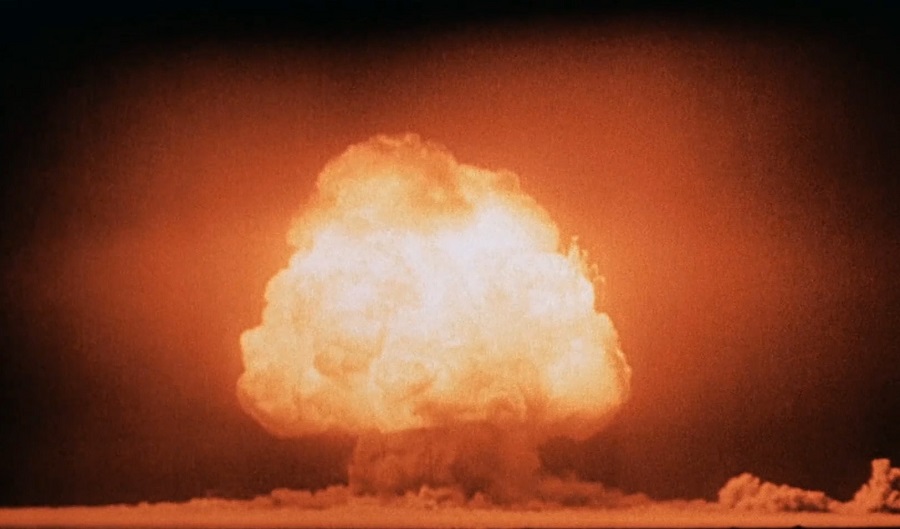

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Project TRINITY was the name given to the war-time effort to produce the first nuclear detonation. A plutonium-fueled implosion device was detonated on 16 July 1945 at the Alamogordo Bombing Range in south-central New Mexico.

Three weeks later, on 6 August, the first uranium-fueled nuclear bomb, a gun-type weapon code-named LITTLE BOY, was detonated over the Japanese city of Hiroshima. On 9 August, the FAT MAN nuclear bomb, a plutonium-fueled implosion weapon identical to the TRINITY device, was detonated over another Japanese city, Nagasaki. Two days later, the Japanese Government informed the United States of its decision to end the war. On 2 September 1945, the Japanese Empire officially surrendered to the Allied Governments, bringing World War II to an end.

In the years devoted to the development and construction of a nuclear weapon, scientists and technicians expanded their knowledge of nuclear fission and developed both the gun-type and the implosion mechanisms to release the energy of a nuclear chain reaction. Their knowledge, however, was only theoretical. They could be certain neither of the extent and effects of such a nuclear chain reaction, nor of the hazards of the resulting blast and radiation. Protective measures could be based only on estimates and calculations. Furthermore, scientists were reasonably confident that the gun-type uranium-fueled device could be successfully detonated, but they did not know if the more complex firing technology required in an implosion device would work. Successful detonation of the TRINITY device showed that implosion would work, that a nuclear chain reaction would result in a powerful detonation, and that effective means exist to guard against the blast and radiation produced.

1.1 Historical Background of Project Trinity

The development of a nuclear weapon was a low priority for the United States before the outbreak of World War II. However, scientists exiled from Germany had expressed concern that the Germans were developing a nuclear weapon. Confirming these fears, in 1939 the Germans stopped all sales of uranium ore from the mines of occupied Czechoslovakia. In a letter sponsored by group of concerned scientists, Albert Einstein informed President Roosevelt that German experiments had shown that an induced nuclear chain reaction was possible and could be used to construct extremely powerful bombs [7; 12].

[All sources cited in the text are listed alphabetically in the reference list at the each page. The number given in the text corresponds to the number of the source document in the reference list.]

In response to the potential threat of a German nuclear weapon, the United States sought a source of uranium to use in determining the feasibility of a nuclear chain reaction. After Germany occupied Belgium in May 1940, the Belgians turned over uranium ore from their holdings in the Belgian Congo to the United States. Then, in March 1941, the element plutonium was isolated, and the plutonium-239 isotope was found to fission as readily as the scarce uranium isotope, uranium-235. The plutonium, produced in a uranium-fueled nuclear reactor, provided the United States with an additional source of material for nuclear weapons [7; 12].

In the summer of 1941, the British Government published a report written by the Committee for Military Application of Uranium Detonation (MAUD). This report stated that a nuclear weapon was possible and concluded that its construction should begin immediately. The MAUD report, and to a lesser degree the discovery of plutonium, encouraged American leaders to think more seriously about developing a nuclear weapon. On 6 December 1941, President Roosevelt appointed the S-1 Committee to determine if the United States could construct a nuclear weapon. Six months later, the S-1 Committee gave the President its report, recommending a fast-paced program that would cost up to $100 million and that might produce the weapon by July 1944 [12].

The President accepted the S-1 Committee’s recommendations. The effort to construct the weapon was turned over to the War Department, which assigned the task to the Army Corps of Engineers. In September 1942, the Corps of Engineers established the Manhattan Engineer District to oversee the development of a nuclear weapon. This effort was code-named the “Manhattan Project”[12].

Within the next two years, the MED built laboratories and production plants throughout the United States. The three principal centers of the Manhattan Project were the Hanford, Washington, Plutonium Production Plant; the Oak Ridge, Tennessee, U-235 Production Plant; and the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory in northern New Mexico. At LASL, Manhattan Project scientists and technicians, directed by Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer,[a] investigated the theoretical problems that had to be solved before a nuclear weapon could be developed [12].

[a. This report identifies by name only those LASL and MED personnel who are well-known historical figures.]

During the first two years of the Manhattan Project, work proceeded at a slow but steady pace. Significant technical problems had to be solved, and difficulties in the production of plutonium, particularly the inability to process large amounts, often frustrated the scientists. Nonetheless, by 1944 sufficient progress had been made to persuade the scientists that their efforts might succeed. A test of the plutonium implosion device was necessary to determine if it would work and what its effects would be. In addition, the scientists were concerned about the possible effects if the conventional explosives in a nuclear device, particularly the more complex implosion-type device, failed to trigger the nuclear reaction when detonated over enemy territory. Not only would the psychological impact of the weapon be lost, but the enemy might recover large amounts of fissionable material.

In March 1944, planning began to test-fire a plutonium-fueled implosion device. At LASL, an organization designated the X-2 Group was formed within the Explosives Division. Its duties were “to make preparations for a field test in which blast, earth shock, neutron and gamma radiation would be studied and complete photographic records made of the explosion and any atmospheric phenomena connected with the explosion” [13]. Dr. Oppenheimer chose the name TRINITY for the project in September 1944 [12].

SOURCES CITED ON THIS PAGE

[7. Groves, Leslie R., LTG, USA (Ret.). Now It Can Be Told: The Story of the Manhattan Project. New York, NY.: Harper and Row. 1962. 444 Pages.]

[12. Lamont, Lansing. Day of TRINITY. New York, NY.: Atheneum. 1965. 331 Pages.]

[13. Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, Public Relations Office. “Los Alamos: Beginning of an Era, 1943-1945.” Atomic Energy Commission. Los Alamos, NM.: LASL. 1967. 65 Pages.]

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.