Aqaba is picturesquely located at the southern end of the wide Wadi Araba, perhaps the driest and most desolate valley in the world, which runs down from the Dead Sea to the Gulf of Akaba.

Continuing Lawrence Launches Arab Desert Campaign,

our selection from With Lawrence in Arabia by Lowell Thomas published in 1924. The selection is presented in fifteen easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Lawrence Launches Arab Desert Campaign.

Time: 1917

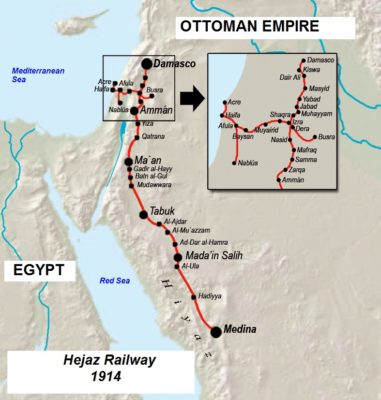

Place: Along the Hejaz Railway

Lawrence had left El Wejh, hundreds of miles to the south, with but two months’ rations. After giving a part of his supplies to the captured Turks, the food situation became critical. Nevertheless the half-starved Arab army, led by this youngster, continued its march through the jagged, barren mountains that bite the North Arabian sky. The news of their victories traveled ahead of them, and when Lawrence arrived at Gueirra, a Turkish post in King Solomon’s Mountains, twenty-five miles from Akaba, at the entrance to an extremely narrow pass known as the Wadi Ithm, the Gueirra garrison came out and laid down their arms without firing a shot. He then proceeded to march his Bedouins on, down the Wadi Ithm to Kethura, another outpost guarding the only land approach to Akaba. There Lawrence charged another garrison and captured several hundred more men. Trekking through the gorge they came to an ancient well at Khadra, where two thousand years before the Romans had constructed a stone dam across the valley, the remains of which can still be seen. The Turks had massed their heavy artillery behind that ruined wall. It constituted the outermost defense of Akaba. By the time the Shereefian army arrived in front of this final barricade the Bedouins of the Amran Darausha and Neiwat tribes, who lived in the desert near Akaba, had heard of the great victories at Fuweilah and Abu el Lissal and were scampering across the lava mountains by the hundreds to join the advancing Arab forces.

The overwhelming defeat of the Turkish battalion at Abu el Lissal was really the first phase of the battle of Akaba. The second consisted in the spectacular maneuver when Lawrence accomplished what the Turks thought impossible and succeeded in leading his scraggly, undisciplined horde of Bedouins through the precipitous King Solomon Mountains, over the old Roman wall, right past the bewildered Turkish artillerymen, and down into Akaba on the morning of July 6, 1917. But to save the Akaba garrison from massacre Lawrence and Nasir had to labor with their fierce followers from sunset to dawn. They would not have succeeded then, had not Nasir walked down the valley into No-Mans’-Land and sat on a rock to make his men quit firing.

Akaba is picturesquely located at the southern end of the wide Wadi Araba, perhaps the driest and most desolate valley in the world, which runs down from the Dead Sea to the Gulf of Akaba. Up this same wadi Moses and the Israelites are believed to have made their way toward the Promised Land, and down this valley rode Mohammed, Ali, Abu Bekr, and Omar. It was here that Mohammed preached many of his first sermons. Beyond a narrow semicircle of date-palms which fringe the shore, lie the blue waters of the now deserted gulf where Solomon’s fleets, Phoenician galleys, and Roman triremes rode at anchor. Behind Akaba loom jagged, volcanic, arid mountains. Like most of the smaller towns of the Near East the place itself is a chaotic jumble of mud huts. Awnings cover the narrow streets, and the stalls in the bazaar are filled with brocades, shabby prayer-rugs, cones of cane-sugar swarming with flies, piles of dates, and dishes of glistening brass and hammered copper.

The Turks and Germans were so paralyzed and bewildered by the unexpected achievement of the Arabs in getting across the mountains and through the passes that they surrendered without further ado. Immediately after the entrance into Akaba a German officer stepped up and saluted Lawrence. He spoke neither Turkish nor Arabic and evidently did not even know there was a revolution in progress.

“What is all this about? What is all this about? Who are these men?” he shouted excitedly.

“They belong to the army of King Hussein” — the Grand Shereef had by this time proclaimed himself king — “who is in revolt against the Turks,” replied Lawrence.

“Who is King Hussein?” asked the German.

“Emir of Mecca and ruler of this part of Arabia, was the reply.

“Ach Himmel! And what am I?” added the German officer in English.

“You are a prisoner.”

“Will they take me to Mecca?”

“No, to Egypt.”

“Is sugar very high over there?”

“Very cheap.”

“Good.” And he marched off, happy to be out of the war, and happier still to be heading for a place where he could have plenty of sugar.

This time the plans of Emir Feisal’s youthful British adviser went through true to form. From now on the Turks were kept on the defensive. They were obliged to weaken their army by splitting it into two parts; one half remained in Medina, and the other defended the pilgrimage railway. If he had wanted to do so Lawrence could have dynamited the railway in so many places that the Turks would have been completely cut off at Medina; then, by bringing up a few long-range naval guns from the Gulf of Aqaba, he could have blown Medina off the map and compelled the garrison to surrender. But he had an excellent reason for not attempting this, as we shall soon see. In his mind he had worked out a far finer and more ambitious scheme, the successful carrying out of which demanded that the Turks should be inveigled into sending down more reinforcements to Medina, and as many guns, camels, mules, armored cars, airplanes, and other war materials as they could be compelled to part with from their other fronts. He hoped they would keep a huge garrison there until the end of the war, which would mean so many less Turks opposing the British armies in Palestine and Mesopotamia; and the supply-trains which would necessarily have to be sent down from Syria might be made a constant source of supply for the Arabs. If Medina were captured and the Turks all driven north, it would deprive Lawrence of this magnificent opportunity of maintaining his army on Turkish supplies. That was far more to his advantage than occupying Medina.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.