In all, Lawrence had now over two hundred thousand fighting men available.

Continuing Lawrence Launches Arab Desert Campaign,

our selection from With Lawrence in Arabia by Lowell Thomas published in 1924. The selection is presented in fifteen easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Lawrence Launches Arab Desert Campaign.

Time: 1917

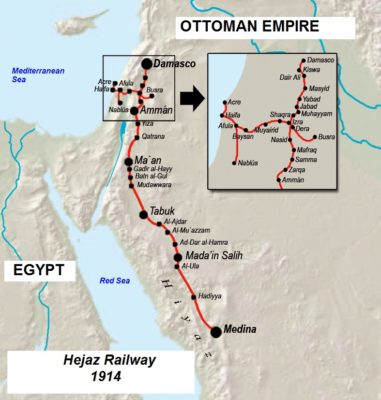

Place: Along the Hejaz Railway

[Continuing Lowell Thomas’ excerpt from Miss Bell’s “The Desert and the Sown.”]

There are good customs among the Arabs, as Namrud said. So he bides his time for months, perhaps for years, until at length opportunity ripens, and the horsemen of his tribe with their allies ride forth and recapture all the flocks that had been carried off and more besides, and the feud enters another phase. The truth is, that the ghazu (raid) is the only industry the desert knows and the only game. As an industry it seems to the commercial mind to be based on a false conception of the laws of supply and demand, but as a game there is much to be said for it. The spirit of adventure finds full scope in it—you can picture the excitement of the night ride across the plain, the rush of the mares in the attack, the glorious popping of rifles and the exhilaration of knowing yourself a fine fellow as you turn homewards with the spoil. It is the best sort of fantasia, as they say in the desert, with a spice of danger behind it. Not that the danger is alarmingly great: a considerable amount of amusement can be got without much bloodshed, and the raiding Arab is seldom bent on killing. He never lifts his hand against women and children, and if here and there a man falls it is almost by accident, since who can be sure of the ultimate destination of a rifle bullet once it is embarked on its lawless course? This is the Arab view of the ghazu.

As they pushed northward from the head of the Gulf of Aqaba, the Hedjaz forces were joined by the Ibn Jazi Howeitat and the Beni Sakhr, two of the best fighting tribes of the whole Arabian Desert. About the same date the Juheinah, the Ateibah, and the Anazeh came riding in on their camels to join Feisal and Lawrence.

After the fall of Aqaba, Lawrence had made several trips to Palestine to confer with Allenby. From that time the British in Palestine and King Hussein’s army were in close cooperation.

The Arab army had been divided into two distinct parts, one known as regulars and the other as irregulars. The regulars were all infantrymen; there were not more than twenty thousand of them. They were either deserters from the Turkish army or men of Arab blood who had been fighting under the sultan’s flag and who had volunteered to join the forces of King Hussein after being taken prisoner by the British in Mesopotamia or in Palestine. At first they were used mainly for garrisoning old Turkish posts captured by the advancing Shereefian horde. Later on, after they had been thoroughly trained, they were used as storm-troops in attacking fortified positions. The Arab regulars were under an Irishman, Colonel P. C. Joyce, who, next to Lawrence, perhaps played a more important part in the Arabian campaign than any other non-Moslem. The irregulars, who were by far the most numerous, were Bedouins mounted on camels and horses. In all, Lawrence had now over two hundred thousand fighting men available.

The battle of Seil el Hasa illustrates the manner in which he handled King Hussein’s forces. A Turkish regiment, under the command of Hamid Fahkri Bey, composed of infantry, cavalry, mountain artillery, and machine-gun squads, was sent over the Hedjaz Railway from Kerak, southeast of the Dead Sea, to recapture the town of Tafileh, which had fallen into the hands of the Arabian army. The Turkish regiment had been hurriedly formed in the Hauran and Amman and was short of supplies.

When the Turks came in contact with the Bedouin patrols at Seil el Hasa, they drove them back into the town of Tafileh. Lawrence and his Shereefian staff had laid out a defensive position on the south bank of the great valley in which Tafileh stands, and Shereef Zeid, youngest of the four sons of King Hussein, occupied that position during the night, with five hundred regulars and irregulars. At the same time, Lawrence sent most of the baggage of his army off in another direction, and all the natives of the town thought the Arab army was running away.

“I think they were,” Lawrence remarked to me. Tafileh was seething with excitement. Sheik Dhiab el Auran, the amateur Sherlock of the Hedjaz, had brought in reports of growing dissatisfaction among the villagers, and rumors of treachery; so Lawrence went down from his housetop, before dawn, into the crowded streets to do a bit of necessary eavesdropping. Dressed in his voluminous robes, he had no difficulty in concealing his identity in the dark. There was much criticism of King Hussein, and the populace was not over-respectful. Every one was screaming with terror, and the town of Tafileh was in a state of tumult. Homes were being speedily vacated, and goods were being bundled through the lattice windows into the crowded streets. Mounted Arabs were galloping up and down, firing wildly into the air and through the palm branches. With each flash of the rifles the cliffs of Tafileh gorge stood out in momentary relief, sharp and clear against the topaz sky. Just at dawn the enemy bullets began to fall, and Lawrence went out to Shereef Zeid and persuaded him to send one of his officers with two fusils-mitrailleurs to support the Arab villagers, who were still holding the southern crest of the foot-hills.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.