He had blown up so many trains that he was as familiar with the Turkish system of transportation and patrols as were the Turks themselves.

Continuing Lawrence Launches Arab Desert Campaign,

our selection from With Lawrence in Arabia by Lowell Thomas published in 1924. The selection is presented in fifteen easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Lawrence Launches Arab Desert Campaign.

Time: 1917

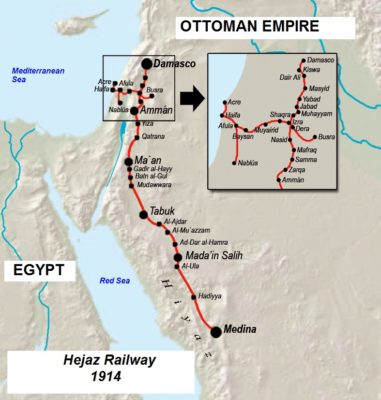

Place: Along the Hejaz Railway

One day Lawrence’s column was trekking along the Wadi Ithm. Behind him rode a thousand Bedouins mounted on the fleetest racing-camels ever brought down the Negb. The Bedouins were improvising strange war-songs describing the deeds of the blond shereef whom General Storrs had introduced to me as “the uncrowned king of Arabia.” Lawrence headed the column. He paid no attention to the song lauding him as a modern Abu Bekr. We were discussing the possibility of ancient Hittite civilization forming the connecting link between the civilizations of Babylon and Nineveh and ancient Crete. But his mind was on other things and suddenly he broke off to remark:

Do you know, one of the most glorious sights I have ever seen is a train-load of Turkish soldiers ascending skyward after the explosion of a tulip!”

Three days later the column started off at night in the direction of the Pilgrim Railway. In support of Lawrence were two hundred Howeitat. After two days’ hard riding across a country more barren than the mountains of the moon, and through valleys reminiscent of Death Valley, California, the raiding column reached a ridge of hills near the important Turkish railway-center and garrisoned town of Maan. At a signal from Lawrence all dismounted, left the camels, walked up to the summit of the nearest hill, and from between sandstone cliffs looked down across the railway track.

This was the same railway that had been built some years before to enable the Turkish Government to keep a closer hand on Arabia through transport of troops. It also simplified the problem of transportation for pilgrims to Medina and Mecca. Medina was garrisoned by an army of over twenty thousand Turks and was strongly fortified. Lawrence and his Arabs could have severed this line completely at any time, but they chose a shrewder policy. Train-load after train-load of supplies and ammunition must be sent down to Medina over that railway. So whenever Lawrence and his followers ran out of food or ammunition they had a quaint little habit of slipping over, blowing up a train or two, looting it, and disappearing into the blue with everything that had been so thoughtfully sent down from Constantinople.

As a result of the experience he gained on these raids, Lawrence’s knowledge of the handling of high explosives was as extensive as his knowledge of archaeology, and he took great pride in his unique ability as a devastator of railways. The Bedouins, on the other hand, were entirely ignorant of the use of dynamite; so Lawrence nearly always planted all of his own mines and took the Bedouins along merely for company and to help carry off the loot.

He had blown up so many trains that he was as familiar with the Turkish system of transportation and patrols as were the Turks themselves. In fact he had dynamited Turkish trains passing along the Hedjaz Railway with such regularity that in Damascus seats in the rear carriage sold for five and six times their normal value. Invariably there was a wild scramble for seats at the rear of a train; because Lawrence nearly always touched off his tulips, as he playfully called his mines, under the engine, with the result that the only carriages damaged were those in front.

There were two important reasons why Lawrence preferred not to instruct the Arabs in the use of high explosives. First of all, he was afraid that the Bedouins would keep on playfully blowing up trains even after the termination of the war. They looked upon it merely as an ideal form of sport, one that was both amusing and lucrative. Secondly, it was extremely dangerous to leave footmarks along the railway line, and he preferred not to delegate tulip planting to men who might be careless.

The column crouched behind great chunks of sandstone for eight hours until a number of patrols had passed by. Lawrence satisfied himself that they were going at intervals of two hours. At midday, while the Turks were having their siesta, Lawrence slipped down to the railway line, and, walking a short distance on the sleepers in his bare feet in order not to leave impressions on the ground which might be seen by the Turks, he picked out what he considered a proper spot for planting a charge. Whenever he merely wanted to derail the engine of a train he would use only a pound of blasting gelatin; when he wanted to blow it up he would use from forty to fifty pounds. On this occasion, in order that no one might be disappointed, he used slightly more than fifty pounds. It took him a little more than an hour to dig a hole between the sleepers, bury the explosive, and run a fine wire underneath the rail, over the embankment, and up the hillside.

Laying a mine is rather a long and tedious task. Lawrence first took off a top layer of railway ballast, which he placed in a bag that he carried under his cloak for that purpose. He next took out enough earth and rock to fill two five-gallon petrol tins. This he carried off to a distance of some fifty yards from the track and scattered along so that it would not be noticed by the Turkish patrols. After filling the cavity with his fifty-pound tulip-seed of dynamite, he put the surface layer of ballast back in place and leveled it off with his hand. As a last precaution he took a camel’s-hair brush, swept the ground smooth, and then, in order not to leave a footprint, walked backward down the bank for twenty yards and with the brush carefully removed all trace of his tracks. He buried the wire for a distance of two hundred yards up the side of the hill and then calmly sat down under a bush, right out in the open, and waited as nonchalantly as though tending a flock of sheep. When the first trains came along the guards stationed on top of the cars and in front of the engine, with their rifles loaded, saw nothing more extraordinary than a lone Bedouin sitting on the hillside with a shepherd’s staff in his hand. Lawrence allowed the front wheels of the engine to pass over the mine, and then, as his column lay there half paralyzed behind the boulders, he sent the current into the gelatin. It exploded with a roar like the falling of a six-story building. An enormous black cloud of smoke and dust went up. With a clanking and clattering of iron the engine rose from the track. It broke squarely in two. The boiler exploded, and chunks of iron and steel showered the country for a radius of three hundred yards. Numerous bits of boiler-plate missed Lawrence by inches.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.