As a result of Lawrence’s victory at Aqaba and his visit to Egypt, the British decided to back the Arabs to the limit in their campaign to win complete independence.

Continuing Lawrence Launches Arab Desert Campaign,

our selection from With Lawrence in Arabia by Lowell Thomas published in 1924. The selection is presented in fifteen easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Lawrence Launches Arab Desert Campaign.

Time: 1917

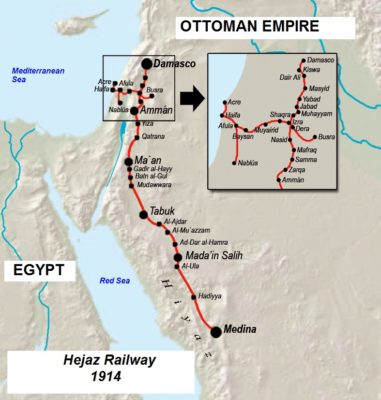

Place: Along the Hejaz Railway

After the capture of Aqaba, Lawrence and his men lived for ten days on unripe dates and on the meat of camels which had been killed in the battle of Abu el Lissal. They were compelled to kill their own riding-camels at the rate of two a day to save themselves and their hundreds of prisoners. Then in order to keep his army from starving, Lawrence jumped on his racing-camel and rode her continuously for twenty-two hours across the uninhabited mountains and desert valleys of the Sinai Peninsula. Completely worn out after this record ride, which came at the end of two months’ continuous fighting and a thousand miles of trekking across one of the most barren parts of the earth and living on soggy unleavened bread and dates and without having a bath for more than a month, he turned his camel over to an M.P. at one of the street corners in Port Tewfik, Suez, walked a little unsteadily into the Sinai Hotel, and ordered a bath. For three hours he remained in the tub with a procession of Berberine boys serving him cool drinks. That day, he declares, was the nearest approach to the Mohammedan idea of paradise that he ever expects to experience. From Suez he went on to Ismailia, the midway station on the canal.

Lawrence’s arrival in Arabia had been unheralded; even G.H.Q. in Cairo were ignorant as to his movements. His exploits first became known when he met General Allenby at Ismailia on the arrival of this new leader who had just been assigned to take over command of the Egyptian Expeditionary Forces.

The incident was dramatic in its simplicity. Allenby had been sent out from London to succeed Sir Archibald Murray as commander-in-chief. He had just landed and was at the railway station in Ismailia walking up and down the platform with Admiral Wemyss. Lawrence, standing near-by in Arab garb, saw the important-looking general with the admiral.

“Who’s that?” he asked of Wemyss’s flag-lieutenant.

“Allenby,” was the reply.

“What’s he doing here?” queried Lawrence.

“He has come out to take Murray’s place.” Lawrence was frightfully pleased.

A few minutes later Lawrence had an opportunity to report to Admiral Wemyss, who had been the godfather of the Arab “show.” He told him that Akaba had been taken but that his men were badly in need of food. The admiral immediately promised to send ships, and a moment later he told Allenby what Lawrence had said. The general sent for him at once. The station was crowded with staff-officers and a throng of vociferous natives who were welcoming Allenby, when out of the mob stepped this bare-footed, fair-faced boy in Bedouin garb.

“What news have you brought,” asked Allenby.

In even, low tones, without any more expression on his face than if he were conveying compliments from the Grand Shereef, Lawrence reported that the Arabs had captured the ancient seaport at the head of the Gulf of Aqaba. He gave all the credit for the victory to the Arabs, making no reference to the part he himself had played in the affair. He conveyed the impression that he was acting as a courier, although, as a matter of fact, the capture of that important point was due entirely to his own leadership and strategical genius.

The general was immensely pleased, because Akaba was the most important point on his right flank and the principal Turkish base on the western coast of the Arabian Peninsula.

Then when Lawrence explained in more detail the plight of the Arab troops Admiral Wemyss promised to send a vessel filled with food to Akaba. But Sir Rosslyn went even beyond that and acted in a way that will immortalize him in Arabian history. The Arabs were afraid lest the Turks should return with reinforcements and capture Akaba; so the admiral moved his office, all his personal effects, and his staff ashore to a hotel in Ismailia, and sent his flag-ship round Sinai to Aqaba for a whole month to bolster up the morale of the Arabs. The presence of this huge floating fortress encouraged the Bedouins and convinced them that they were not going to be obliged to play a lone hand against the Turkish Empire. The British flag-ship was more tangible evidence of the strength of Britain than these desert nomads had ever seen before.

Admiral Wemyss also lent Lawrence and his Arabs twenty machine-guns from his ships and several naval guns. The latter are still “somewhere” in Arabia, probably mounted on the roof of Auda Abu Tayi’s mud palace. Several months after the termination of the war Lawrence received a letter from the Admiralty asking him kindly to return one of their long-range guns which had been taken ashore for the Arab show. He replied that he was very sorry but that he had “mislaid it.”

As a result of Lawrence’s victory at Akaba and his visit to Egypt, the British decided to back the Arabs to the limit in their campaign to win complete independence. The young archaeologist was sent back to Akaba with unlimited resources, and within a few months he had conducted the campaign in such a brilliant manner that he was raised in rank from lieutenant to lieutenant-colonel, despite the fact that he hardly knew the difference between “right incline” and “present arms.”

The Germans and Turks were not long in finding out that there was a mysterious power giving inspiration to the Arabs. Through their spies they discovered that Lawrence was the guiding spirit of the whole Arabian revolution. They offered rewards up to fifty thousand pounds for his capture dead or alive. But the Bedouins would not have betrayed their leader for all the gold in the fabled mines of Solomon.

The fall of Aqaba, next to the capture of the holy city of Mecca, was the most significant event of the Arabian revolution, because it unified the Arabs whom Lawrence had already won over to the cause of the revolution and gave them confidence in themselves.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.