This series has fifteen easy 5-minute installments. This first installment: The Battle at the Wells of Abu El Lissal.

Introduction

After initial successes against the Ottoman Turks, the Arab uprising stalled. This is that story of how a junior British Officer named Lawrence served to unite the warring tribes, bring in the British support, and attack north.

This selection is from With Lawrence in Arabia by Lowell Thomas published in 1924. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Lowell Thomas (1892-1981) was an American writer and broadcaster. He was television’s first news anchor.

Time: 1917

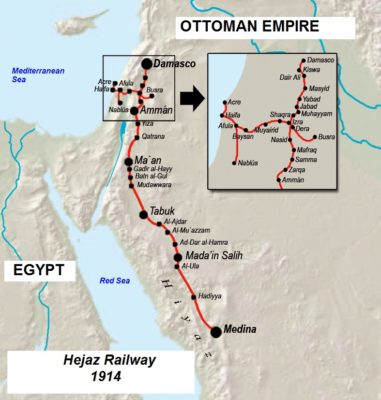

Place: Along the Hejaz Railway

Simultaneously with Feisal’s attack on the small Red Sea ports of Yenbo and El Wejh, his brother Abdulla appeared out of the desert several miles to the east, near Medina. He was accompanied by a riding-party mounted on she racing-camels. These raiders wiped out a few enemy patrols, blew up several sections of track, and left a formal letter tacked, in full view, on one of the sleepers, and addressed to the Turkish commander-in-chief, describing in redundant and lurid detail what his fate would be if he lingered longer in Arabia.

The Turkish forces advancing on Mecca received news of the fall of Yenbo and El Wejh, more than a hundred miles to the northwest of them, and of Shereef Abdulla’s raids a hundred miles to the northeast, at almost the same moment. They were amazed and bewildered, for a few days previously the Arab army had been sitting in front of them at Rabegh.

Thanks to the sniping of Emir Zeid’s handful of followers by day and to small raids by night, the Turks had been tricked into thinking the main Hedjaz army still there, but now there appeared to be Arab armies on all sides of them. The relentless rays of the sun, beating down with blistering ferocity on the parched region where they encamped, not only increased their thirst but stimulated their imagination as well. To their feverish, sunken eyes, every mirage now seemed to be a cloud of Bedouin horsemen. Each hour brought camel couriers with news of raids on El Ula, Medain Saleh, and other stations north of Medina and of the capture of two more of their Red Sea garrisons at Dhaba and Moweilah. Thoroughly frightened by the news of these unexpected reverses, as well as by the rumors of fictitious Arab victories circulated purposely among them by Lawrence’s secret agents, the Turks, panic-stricken, fled back to defend their base at Medina and to defend the railway, which was their sole line of communication with Syria and Turkey.

In the north of Holy Arabia, near the head of the Gulf of Aqaba, the Turks had another garrison far more important than any as yet taken in the campaign except the garrisons at Mecca and Jeddah. Before Feisal’s followers could hope to sweep their ancient enemy out of all the Hedjaz, excepting Medina, this important stronghold at the head of the gulf must be accounted for. This accomplished, Lawrence had in mind a far bolder and vaster plan which he hoped to execute.

Of all the strategic places along the west coast of Arabia north of Aden, the most important from a military standpoint is the ancient seaport of Akaba, once the chief naval base of King Solomon’s fleet, and also one of the first places where the Prophet Mohammed preached and made his headquarters. For any army attempting to invade Egypt or strike at the Suez Canal from the east, Akaba must be the left flank, as it must be the right flank for any army setting out from Egypt to invade Palestine and Syria. From the beginning of the war the Turks had maintained a large garrison there, both because they intended to wrest Egypt from the British, and because it was essential to the security of the Hedjaz Railway.

It was Lawrence’s intention to capture Akaba and make it the base for an Arab invasion of Syria! This was a truly ambitious and portentous plan.

On June 18, 1917, with only eight hundred Bedouins of the Toweiha tribe, two hundred of the Sherart, and ninety of the Kawachiba, he set out from El Wejh for the head of the Gulf of Akaba, three hundred miles farther north. This force was headed by Shereef Nasir, a remote descendant of Mohammed and one of Feisal’s ablest lieutenants. As usual, Lawrence went along to advise the Arab commander; he always made it a point to act through one of the native leaders, and much of his success may be attributed to his tact in making the Arabs believe that they were conducting the campaign themselves.

The advance on Akaba is an illustration of how ably Lawrence handled Feisal’s army, in spite of his complete lack of military training and experience. In order to outwit the Turkish commander at Medina he led a flying column nearly one thousand miles to the north of El Wejh; but instead of going right up the coast toward Akaba, he led them far into the interior, across the Hedjaz Railway not far from Medina, where they blew up several miles of track on the way, then through the Wadi Sirhan, famous for its venomous reptiles, where some of his men died of snake-bite, then across the territory of the Howeitat tribe east of the Dead Sea, and still on, north into the land of Moab. He even led a party of picked men through the Turkish lines by night, dynamited a train near Amman (the ancient Greek city of Philadelphia), blew up a bridge near Deraa, the most important railway junction just south of Damascus, and mined another several hundred miles behind the Turkish front-line trenches, near the Syrian industrial city of Homs.

It was possible for Lawrence to conduct raids on such a grand scale only because of the extra ordinary mobility of his forces. With his camel corps he could cruise across the desert for six weeks without returning to his supply base. As long as the members of his party kept to the desert and out of sight of the Turkish fortified posts along the frontiers of Palestine and Syria, they were as safe as though they were on another planet. When they saw an opportunity to dash in and make a surprise attack, they would do so, and then dash back into the desert where the Turks dared not follow because they neither had the camels, the intimate knowledge of the desert, nor the phenomenal powers of endurance which the Bedouins possessed. During a six weeks’ expedition, Lawrence’s followers would live on nothing but unleavened bread. Each man carried a half-sack of flour weighing forty-five pounds, enough to enable him to trek two thousand miles without obtaining fresh supplies. They could get along comfortably on a mouthful of water a day when on the march, but wells were rarely more than two or three days’ march apart, so that they seldom suffered from thirst.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.