It is one of the most difficult languages in the world to master.

Continuing Lawrence Launches Arab Desert Campaign,

our selection from With Lawrence in Arabia by Lowell Thomas published in 1924. The selection is presented in fifteen easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Lawrence Launches Arab Desert Campaign.

Time: 1917

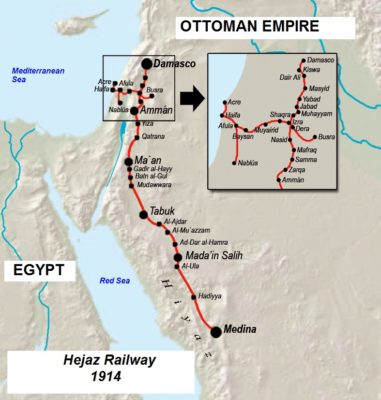

Place: Along the Hejaz Railway

His only European companion on some of his wildest train-blowing parties was a daring Australian machine-gunner, Sergeant Yells by name. He was a glutton for excitement and a tiger in a fight. On one occasion, when out with a raiding-party of Abu Tayi, Yells accounted for between thirty and forty Turks with his Lewis gun. When the loot was divided among the Bedouins, Yells, in true Australian fashion, insisted on having his share. So Lawrence handed him a Persian carpet and a fancy Turkish cavalry sword.

Shereefs Ali and Abdullah also played an important part in the raids on the Hedjaz Railway and in the capture of great convoys of Turkish camels near Medina. In 1917 Lawrence and his associates, in coöperation with Feisal, Ali, Abdullah, and Zeid, blew up twenty-five Turkish trains, tore up fifteen thousand rails, and destroyed fifty-seven bridges and culverts. During the eighteen months that he led the Arabs, they dynamited seventy-nine trains and bridges! It is a remarkable fact that he participated in only one such expedition that turned out unsatisfactorily. General Allenby, in one of his reports, said that Colonel Lawrence had made train-wrecking the national sport of Arabia!

Later in the campaign, near Deraa, the most important railway-junction south of Damascus, Lawrence touched off one of his tulips under the driving-wheels of a particularly long and heavily armed train. It turned out that Djemal Pasha, the commander-in-chief of the Turkish armies, was on board with nearly a thousand troops. Djemal hopped out of his saloon and, followed by all his staff, jumped into a ditch.

Lawrence had less than sixty Bedouins with him, but all were members of his personal body-guard and famous fighters. In spite of the overwhelming odds, the young Englishman and his Arabs fought a pitched battle in which 125 Turks were killed and Lawrence lost a third of his own force. The remainder of the Turks finally rallied around their commander-in-chief, and Lawrence and his Arabs had to show their heels.

At every station along the Hedjaz-Pilgrim Railway were one or two bells which the Turkish officials rang as a warning to passengers when the train was ready to start. Nearly all of them now decorate the homes of Lawrence’s friends. Along with them are a dozen or more Turkish mile-posts and the number-plates from half the engines which formerly hauled trains over the line from Damascus to Medina. Lawrence and his associates collected these in order to confirm their victories. While in Arabia, I often heard the half-jocular, half-serious remark that Lawrence would capture a Turkish post merely for the sake of adding another bell to his collection; and it was no uncommon thing to see Lawrence, or one of his officers, walking stealthily along the railway embankment, between patrols, searching for the iron post marking Kilo 1000 south of Damascus. Once found, they would cut it off with a tulip-bud—a stick of dynamite. When not engaged in a major movement against the Turks or in mobilizing the Bedouins, Lawrence usually spent his time blowing up trains and demolishing track.

So famous did this young archaeologist become throughout the Near East as a dynamiter of bridges and trains that after the final defeat of the Turkish armies, when word reached Cairo that Lawrence would soon be passing through Egypt en route to Paris, General Watson, G. O. C. of troops, jocularly announced that he was going to detail a special detachment to guard Kasr el Nil, the Brooklyn Bridge of Egypt, which crosses the Nile from Cairo to the residential suburb of Gazireh.

It had been rumored that Lawrence was dissatisfied at having finished up the campaign with the odd number of seventy-nine mine-laying parties to his credit. So the story spread up and down along the route of the Milk and Honey Railway between Egypt and Palestine that he proposed to make it an even eighty and wind up his career as a dynamiter in an appropriate manner by planting a few farewell tulips under the Kasr el Nil, just outside the door of the British military headquarters.

While Lawrence was traveling from sheik to sheik and from shereef to shereef, urging them, with the eloquence of all the desert dialects at his command, to join in the campaign against the Turks, squadrons of German airplanes were swarming down from Constantinople in a winged attempt to frighten the Arabian army with their strange devil-birds. But the Arabs refused to be intimidated. Instead, they insisted that their resourceful British leader should get them some “fighting swallows” too.

Not long after a particularly obnoxious German air raid over Aqaba, a royal courier galloped up to Lawrence’s tent on his racing dromedary. Without even waiting for his mount to kneel, he slid off the camel’s hump and delivered a scroll on which was inscribed the following:

O faithful one! Thy Government hath airplanes as the locusts. By the Grace of Allah I implore thee to ask thy King to dispatch us a dozen or so.

Hussein.

The people of Arabia are exceedingly ornate and poetical in expressing themselves. They swear by the splendor of light and the silence of night and love to talk in imagery as rich as the colors in their Turkoman prayer-rugs.

An American typewriting concern startled some people by advertising that more people use the Arabic alphabet than use either Roman or Chinese characters. They are very proud of their language and call it the language of the angels; they believe it is spoken in heaven. It is one of the most difficult languages in the world to master. According to our way of thinking the Arabs begin at the end of a sentence and write backward. They have 450 words meaning “line,” 822 words meaning “camel,” and 1037 words meaning “sword.” Their language is full of color. They call a hobo “a son of the road,” and a jackal “a son of howling.” Arab dispatch writers penned their accounts in picturesque vein. “The fighting was worth seeing,” wrote Emir Abdullah to Colonel Lawrence. “The armed locomotives were escaping with the coaches of the train like a serpent beaten on the head.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.