They differed from the rest of the world -— even the world of America, and infinitely more the world of Europe -— in dress, in customs, and in mode of life.

Continuing Frontiersmen Before the American Revolution,

our selection from The Winning of the West by Theodore Roosevelt published in 1889. The selection is presented in nine easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Frontiersmen Before the American Revolution.

Time: 1769-1774

Place: Western Pennsylvania

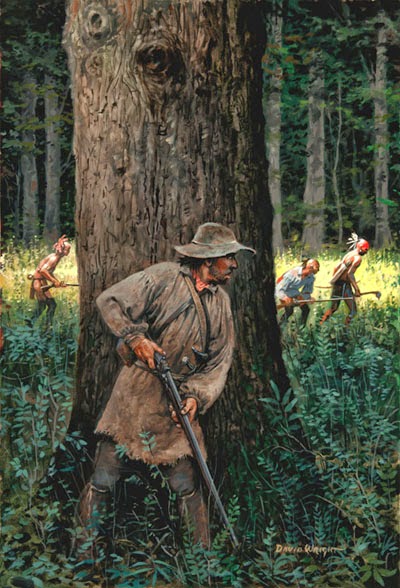

Fair use image from The Scots-Irish.

A single generation, passed under the hard conditions of life in the wilderness, was enough to weld together into one people the representatives of these numerous and widely different races; and the children of the next generation became indistinguishable from one another. Long before the first Continental Congress assembled, the backwoodsmen, whatever their blood, had become Americans, one in speech, thought, and character, clutching firmly the land in which their fathers and grandfathers had lived before them. They had lost all remembrance of Europe and all sympathy with things European; they had become as emphatically products native to the soil as were the tough and supple hickories out of which they fashioned the handles of their long, light axes. Their grim, harsh, narrow lives were yet strangely fascinating and full of adventurous toil and danger; none but natures as strong, as freedom-loving, and as full of bold defiance as theirs could have endured existence on the terms which these men found pleasurable. Their iron surroundings made a mold which turned out all alike in the same shape. They resembled one another, and they differed from the rest of the world -— even the world of America, and infinitely more the world of Europe -— in dress, in customs, and in mode of life.

Where their lands abutted on the more settled districts to the eastward, the population was of course thickest, and their peculiarities least. Here and there at such points they built small backwoods burgs or towns, rude, straggling, unkempt villages, with a store or two, a tavern, -— sometimes good, often a “scandalous hog-sty,” where travelers were devoured by fleas, and every one slept and ate in one room,[1] -— a small log school-house, and a little church, presided over by a hard-featured Presbyterian preacher, gloomy, earnest, and zealous, probably bigoted and narrow-minded, but nevertheless a great power for good in the community.[2]

[1: MS. Journal of Matthew Clarkson, 1766. See also “Voyage dans les Etats-Unis,” La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, Paris, L’an, VII., I., 104.]

[2: The borderers had the true Calvinistic taste in preaching. Clarkson, in his journal of his western trip, mentions with approval a sermon he heard as being “a very judicious and alarming discourse.”]

However, the backwoodsmen as a class neither built towns nor loved to dwell therein. They were to be seen at their best in the vast, interminable forests that formed their chosen home. They won and kept their lands by force, and ever lived either at war or in dread of war. Hence, they settled always in groups of several families each, all banded together for mutual protection. Their red foes were strong and terrible, cunning in council, dreadful in battle, merciless beyond belief in victory. The men of the border did not overcome and dispossess cowards and weaklings; they marched forth to spoil the stout-hearted and to take for a prey the possessions of the men of might. Every acre, every rood of ground which they claimed had to be cleared by the axe and held with the rifle. Not only was the chopping down of the forest the first preliminary to cultivation, but it was also the surest means of subduing the Indians, to whom the unending stretches of choked woodland were an impenetrable cover behind which to move unseen, a shield in making assaults, and a strong tower of defense in repelling counter-attacks. In the conquest of the west the backwoods axe, shapely, well-poised, with long haft and light head, was a servant hardly standing second even to the rifle; the two were the national weapons of the American backwoodsman and in their use, he has never been excelled.

When a group of families moved out into the wilderness, they built themselves a station or stockade fort; a square palisade of upright logs, loop-holed, with strong blockhouses as bastions at the corners. One side at least was generally formed by the backs of the cabins themselves, all standing in a row; and there was a great door or gate, that could be strongly barred in case of need. Often no iron whatever was employed in any of the buildings. The square inside contained the provision sheds and frequently a strong central blockhouse as well. These forts, of course, could not stand against cannon, and they were always in danger when attacked with fire; but save for this risk of burning they were very effectual defences against men without artillery, and were rarely taken, whether by whites or Indians, except by surprise. Few other buildings have played so important a part in our history as the rough stockade fort of the backwoods.

The families only lived in the fort when there was war with the Indians and even then, not in the winter. At other times they all separated out to their own farms, universally called clearings, as they were always made by first cutting off the timber. The stumps were left to dot the fields of grain and Indian corn. The corn in especial was the stand-by and invariable resource of the western settler; it was the crop on which he relied to feed his family, and when hunting or on a war trail the parched grains were carried in his leather wallet to serve often as his only food. But he planted orchards and raised melons, potatoes, and many other fruits and vegetables as well; and he had usually a horse or two, cows, and perhaps hogs and sheep, if the wolves and bears did not interfere. If he was poor his cabin was made of unhewn logs, and held but a single room; if well-to-do, the logs were neatly hewed, and besides the large living- and eating-room with its huge stone fireplace, there was also a small bedroom and a kitchen, while a ladder led to the loft above, in which the boys slept. The floor was made of puncheons, great slabs of wood hewed carefully out, and the roof of clapboards. Pegs of wood were thrust into the sides of the house, to serve instead of a wardrobe; and buck antlers, thrust into joists, held the ever-ready rifles. The table was a great clapboard set on four wooden legs; there were three-legged stools, and in the better sort of houses old-fashioned rocking-chairs.[3] The couch or bed was warmly covered with blankets, bear-skins, and deer-hides.[4]

[3: McAfee MSS.]

[4: In the McAfee MSS. there is an amusing mention of the skin of a huge bull elk, killed by the father, which the youngsters christened “old ellick”; they used to quarrel for the possession of it on cold nights, as it was very warm, though if the hairside was turned in it became slippery and apt to slide off the bed.]

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.