Each family did everything that could be done for itself.

Continuing Frontiersmen Before the American Revolution,

our selection from The Winning of the West by Theodore Roosevelt published in 1889. The selection is presented in nine easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Frontiersmen Before the American Revolution.

Time: 1769-1774

Place: Western Pennsylvania

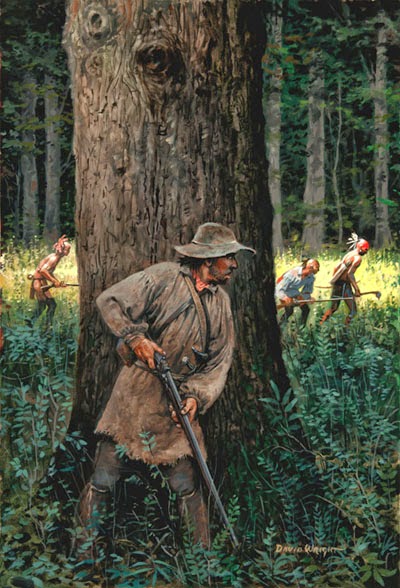

Fair use image from The Scots-Irish.

A wedding was always a time of festival. If there was a church anywhere near, the bride rode thither on horseback behind her father, and after the service her pillion was shifted to the bridegroom’s steed.[1] If, as generally happened, there was no church, the groom and his friends, all armed, rode to the house of the bride’s father, plenty of whisky being drunk, and the men racing recklessly along the narrow bridle-paths, for there were few roads or wheeled vehicles in the backwoods. At the bride’s house the ceremony was performed, and then a huge dinner was eaten, after which the fiddling and dancing began, and were continued all the afternoon, and most of the night as well. A party of girls stole off the bride and put her to bed in the loft above; and a party of young men then performed the like service for the groom. The fun was hearty and coarse, and the toasts always included one to the young couple, with the wish that they might have many big children; for as long as they could remember the backwoodsmen had lived at war, while looking ahead they saw no chance of its ever stopping, and so each son was regarded as a future warrior, a help to the whole community.[2] The neighbors all joined again in chopping and rolling the logs for the young couple’s future house, then in raising the house itself, and finally in feasting and dancing at the house-warming.

[1: Watson.]

[2: Doddridge.]

Funerals were simple, the dead body being carried to the grave in a coffin slung on poles and borne by four men.

There was not much schooling, and few boys or girls learnt much more than reading, writing, and ciphering up to the rule of three.[3] Where the school-houses existed they were only dark, mean log-huts, and if in the southern colonies, were generally placed in the so-called “old fields,” or abandoned farms grown up with pines. The schoolmaster boarded about with the families; his learning was rarely great, nor was his discipline good, in spite of the frequency and severity of the canings. The price for such tuition was at the rate of twenty shillings a year, in Pennsylvania currency.[4]

[3: McAfee MSS.]

[4: Watson.]

Each family did everything that could be done for itself. The father and sons worked with axe, hoe, and sickle. Almost every house contained a loom, and almost every woman was a weaver. Linsey-woolsey, made from flax grown near the cabin, and of wool from the backs of the few sheep, was the warmest and most substantial cloth; and when the flax crop failed and the flocks were destroyed by wolves, the children had but scanty covering to hide their nakedness. The man tanned the buckskin, the woman was tailor and shoemaker, and made the deerskin sifters to be used instead of bolting-cloths. There were a few pewter spoons in use; but the table furniture consisted mainly of hand-made trenchers, platters, noggins, and bowls. The cradle was of peeled hickory bark.[5] Ploughshares had to be imported, but harrows and sleds were made without difficulty; and the cooper work was well done. Chaff beds were thrown on the floor of the loft, if the house-owner was well off. Each cabin had a hand-mill and a hominy block; the last was borrowed from the Indians, and was only a large block of wood, with a hole burned in the top, as a mortar, where the pestle was worked. If there were any sugar maples accessible, they were tapped every year.

[5: McAfee MSS. See also Doddridge and Watson.]

But some articles, especially salt and iron, could not be produced in the backwoods. In order to get them each family collected during the year all the furs possible, these being valuable and yet easily carried on pack-horses, the sole means of transport. Then, after seeding time, in the fall, the people of a neighborhood ordinarily joined in sending down a train of peltry-laden packhorses to some large seacoast or tidal-river trading town, where their burdens were bartered for the needed iron and salt. The unshod horses all had bells hung round their neck; the clappers were stopped during the day, but when the train was halted for the night, and the horses were hobbled and turned loose, the bells were once more unstopped.[6] Several men accompanied each little caravan, and sometimes they drove with them steers and hogs to sell on the seacoast. A bushel of alum salt was worth a good cow and calf, and as each of the poorly fed, undersized pack animals could carry but two bushels, the mountaineers prized it greatly, and instead of salting or pickling their venison, they jerked it, by drying it in the sun or smoking it over a fire.

[6: Doddridge, 156. He gives an interesting anecdote of one man engaged in helping such a pack-train, the bell of whose horse was stolen. The thief was recovered, and whipped as a punishment, the owner exclaiming as he laid the strokes lustily on: “Think what a rascally figure I should make in the streets of Baltimore without a bell on my horse.” He had never been out of the woods before; he naturally wished to look well on his first appearance in civilized life, and it never occurred to him that a good horse was left without a bell anywhere.]

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.