The duties and rights of each member of the family were plain and clear.

Continuing Frontiersmen Before the American Revolution,

our selection from The Winning of the West by Theodore Roosevelt published in 1889. The selection is presented in nine easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Frontiersmen Before the American Revolution.

Time: 1769-1774

Place: Western Pennsylvania

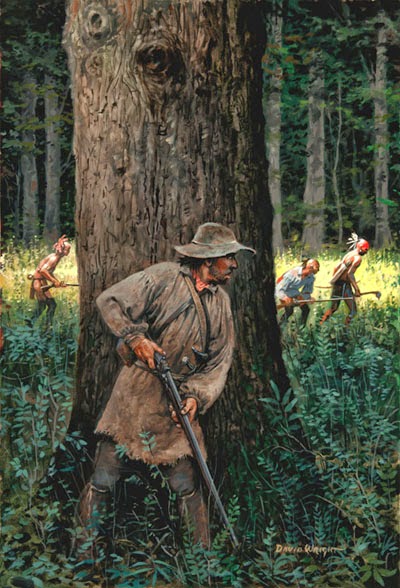

Fair use image from The Scots-Irish.

These clearings lay far apart from one another in the wilderness. Up to the door-sills of the log-huts stretched the solemn and mysterious forest. There were no openings to break its continuity; nothing but endless leagues on leagues of shadowy, wolf-haunted woodland. The great trees towered aloft till their separate heads were lost in the mass of foliage above, and the rank underbrush choked the spaces between the trunks. On the higher peaks and ridge-crests of the mountains there were straggling birches and pines, hemlocks and balsam firs;[1] elsewhere, oaks, chestnuts, hickories, maples, beeches, walnuts, and great tulip trees grew side by side with many other kinds. The sunlight could not penetrate the roofed archway of murmuring leaves; through the gray aisles of the forest men walked always in a kind of mid-day gloaming. Those who had lived in the open plains felt when they came to the backwoods as if their heads were hooded. Save on the border of a lake, from a cliff top, or on a bald knob — that is, a bare hill-shoulder, — they could not anywhere look out for any distance.

[1: On the mountains the climate, flora, and fauna were all those of the north, not of the adjacent southern lowlands. The ruffed grouse, red squirrel, snow bird, various Canadian warblers, and a peculiar species of boreal field-mouse, the evotomys, are all found as far south as the Great Smokies.]

All the land was shrouded in one vast forest. It covered the mountains from crest to river-bed, filled the plains, and stretched in somber and melancholy wastes towards the Mississippi. All that it contained, all that lay hid within it and beyond it, none could tell; men only knew that their boldest hunters, however deeply they had penetrated, had not yet gone through it, that it was the home of the game they followed and the wild beasts that preyed on their flocks, and that deep in its tangled depths lurked their red foes, hawk-eyed and wolf-hearted.

Backwoods society was simple, and the duties and rights of each member of the family were plain and clear. The man was the armed protector and provider, the bread-winner; the woman was the housewife and child-bearer. They married young and their families were large, for they were strong and healthy, and their success in life depended on their own stout arms and willing hearts. There was everywhere great equality of conditions. Land was plenty and all else scarce; so courage, thrift, and industry were sure of their reward. All had small farms, with the few stock necessary to cultivate them; the farms being generally placed in the hollows, the division lines between them, if they were close together, being the tops of the ridges and the watercourses, especially the former. The buildings of each farm were usually at its lowest point, as if in the center of an amphitheater.[2] Each was on an average of about 400 acres,[3] but sometimes more.[4] Tracts of low, swampy grounds, possibly some miles from the cabin, were cleared for meadows, the fodder being stacked, and hauled home in winter.

[2: Doddridge’s “Settlements and Indian Wars,” (133) written by an eyewitness; it is the most valuable book we have on old-time frontier ways and customs.]

[3: The land laws differed at different times in different colonies; but this was the usual size at the outbreak of the Revolution, of the farms along the western frontier, as under the laws of Virginia, then obtaining from the Holston to the Alleghany, this amount was allotted every settler who built a cabin or raised a crop of corn.]

[4: Beside the right to 400 acres, there was also a preemption right to 1,000 acres more adjoining to be secured by a land-office warrant. As between themselves the settlers had what they called “tomahawk rights,” made by simply deadening a certain number of trees with a hatchet. They were similar to the rights conferred in the west now by what is called a “claim shack” or hut, built to hold some good piece of land; that is, they conferred no title whatever, except that sometimes men would pay for them rather than have trouble with the claimant.]

Each backwoodsman was not only a small farmer but also a hunter; for his wife and children depended for their meat upon the venison and bear’s flesh procured by his rifle. The people were restless and always on the move. After being a little while in a place, some of the men would settle down permanently, while others would again drift off, farming and hunting alternately to support their families.[5] The backwoodsman’s dress was in great part borrowed from his Indian foes. He wore a fur cap or felt hat, moccasins, and either loose, thin trousers, or else simply leggings of buckskin or elk-hide, and the Indian breech-clout. He was always clad in the fringed hunting-shirt, of homespun or buckskin, the most picturesque and distinctively national dress ever worn in America. It was a loose smock or tunic, reaching nearly to the knees, and held in at the waist by a broad belt, from which hung the tomahawk and scalping-knife.[6] His weapon was the long, small-bore, flint-lock rifle, clumsy, and ill-balanced, but exceedingly accurate. It was very heavy, and when upright, reached to the chin of a tall man; for the barrel of thick, soft iron, was four feet in length, while the stock was short, and the butt scooped out. Sometimes it was plain, sometimes ornamented. It was generally bored out -— or, as the expression then was, “sawed out” -— to carry a ball of seventy, more rarely of thirty or forty, to the pound; and was usually of backwoods manufacture.[7] The marksman almost always fired from a rest, and rarely at a very long range; and the shooting was marvelously accurate.[8]

[5: McAfee MSS. (particularly Autobiography of Robert McAfee).]

[6: To this day it is worn in parts of the Rocky Mountains, and even occasionally, here and there, in the Alleghanies.]

[7: The above is the description of one of Boon’s rifles, now in the possession of Col. Durrett. According to the inscription on the barrel it was made at Louisville (Ky.), in 1782, by M. Humble. It is perfectly plain; whereas one of Floyd’s rifles, which I have also seen, is much more highly finished, and with some ornamentation.]

[8: For the opinion of a foreign military observer on the phenomenal accuracy of backwoods marksmanship, see General Victor Collot’s “Voyage en Amérique,” p. 242.]

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.