The first lesson the backwoodsmen learnt was the necessity of self-help; the next, that such a community could only thrive if all joined in helping one another.

Continuing Frontiersmen Before the American Revolution,

our selection from The Winning of the West by Theodore Roosevelt published in 1889. The selection is presented in nine easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Frontiersmen Before the American Revolution.

Time: 1769-1774

Place: Western Pennsylvania

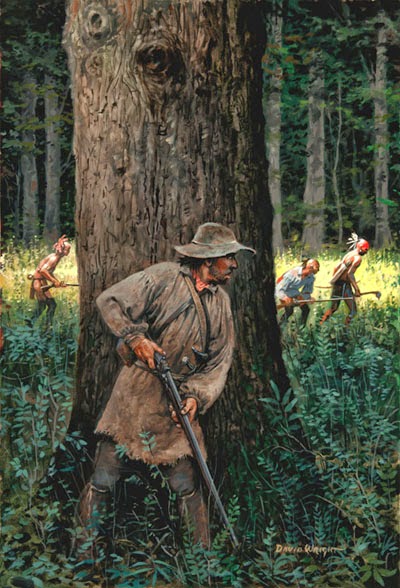

Fair use image from The Scots-Irish.

In the backwoods there was very little money; barter was the common form of exchange, and peltries were often used as a circulating medium, a beaver, otter, fisher, dressed buckskin or large bearskin being reckoned as equal to two foxes or wildcats, four coons, or eight minks.[1] A young man inherited nothing from his father but his strong frame and eager heart; but before him lay a whole continent wherein to pitch his farm, and he felt ready to marry as soon as he became of age, even though he had nothing but his clothes, his horses, his axe, and his rifle.[2] If a girl was well off, and had been careful and industrious, she might herself bring a dowry, of a cow and a calf, a brood mare, a bed well stocked with blankets, and a chest containing her clothes[3] — the latter not very elaborate, for a woman’s dress consisted of a hat or poke bonnet, a “bed gown,” perhaps a jacket, and a linsey petticoat, while her feet were thrust into coarse shoepacks or moccasins. Fine clothes were rare; a suit of such cost more than 200 acres of good land.[4]

[1: MS. copy of Matthew Clarkson’s Journal in 1766.]

[2: McAfee MSS. (Autobiography of Robert R. McAfee).]

[3: Ibid.]

[4: Memoirs of the Hist. Soc. of Penn., 1826. Account of first settlements, etc., by John Watson (1804).]

The first lesson the backwoodsmen learnt was the necessity of self-help; the next, that such a community could only thrive if all joined in helping one another. Log-rollings, house-raisings, house-warmings, corn-shuckings, quiltings, and the like were occasions when all the neighbors came together to do what the family itself could hardly accomplish alone. Every such meeting was the occasion of a frolic and dance for the young people, whisky and rum being plentiful, and the host exerting his utmost power to spread the table with backwoods delicacies — bear-meat and venison, vegetables from the “truck patch,” where squashes, melons, beans, and the like were grown, wild fruits, bowls of milk, and apple pies, which were the acknowledged standard of luxury. At the better houses there was metheglin or small beer, cider, cheese, and biscuits.[5] Tea was so little known that many of the backwoods people were not aware it was a beverage and at first attempted to eat the leaves with salt or butter.[6]

[5: Ibid. An admirable account of what such a frolic was some thirty-five years later is to be found in Edward Eggleston’s “Circuit Rider.”]

[6: Such incidents are mentioned again and again by Watson, Milfort, Doddridge, Carr, and other writers.]

The young men prided themselves on their bodily strength and were always eager to contend against one another in athletic games, such as wrestling, racing, jumping, and lifting flour-barrels; they also sought distinction in vying with one another at their work. Sometimes they strove against one another singly, sometimes they divided into parties, each bending all its energies to be first in shucking a given heap of corn or cutting (with sickles) an allotted patch of wheat. Among the men the bravos or bullies often were dandies also in the backwoods fashions, wearing their hair long and delighting in the rude finery of hunting-shirts embroidered with porcupine quills; they were loud, boastful, and profane, given to coarsely bantering one another. Brutally savage fights were frequent; the combatants, who were surrounded by rings of interested spectators, striking, kicking, biting, and gouging. The fall of one of them did not stop the fight, for the man who was down was maltreated without mercy until he called “enough.” The victor always bragged savagely of his prowess, often leaping on a stump, crowing and flapping his arms. This last was a thoroughly American touch but otherwise one of these contests was less a boxing match than a kind of backwoods pankration, no less revolting than its ancient prototype of Olympic fame. Yet, if the uncouth borderers were as brutal as the highly polished Greeks, they were more manly; defeat was not necessarily considered disgrace, a man often fighting when he was certain to be beaten, while the onlookers neither hooted nor pelted the conquered. We first hear of the noted scout and Indian fighter, Simon Kenton, as leaving a rival for dead after one of these ferocious duels and fleeing from his home in terror of the punishment that might follow the deed.[7] Such fights were specially frequent when the backwoodsmen went into the little frontier towns to see horse races or fairs.

[7: McClung’s “Western Adventures.” All eastern and European observers comment with horror on the border brawls, especially the eye-gouging. Englishmen, of course, in true provincial spirit, complacently contrasted them with their own boxing fights; Frenchmen, equally of course, were more struck by the resemblances than the differences between the two forms of combat. Milfort gives a very amusing account of the “Anglo-Américains d’une espèce particulière,” whom he calls “crakeurs ou gaugeurs,” (crackers or gougers). He remarks that he found them “tous borgnes,” (as a result of their pleasant fashion of eye-gouging — a backwoods bully in speaking of another would often threaten to “measure the length of his eye-strings,”) and that he doubts if there can exist in the world “des hommes plus méchants que ces habitants.”

These fights were among the numerous backwoods habits that showed Scotch rather than English ancestry. “I attempted to keep him down, in order to improve my success, after the manner of my own country.” (“Roderick Random”).]

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.