The most pressing danger to the republic lay in the clerical monopoly of public education.

Continuing France Separates Church and State,

with a selection from special article to Great Events by Famous Historians, volume 20 by Henry H. Sparling published in 1914. This selection is presented in 3 easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in France Separates Church and State.

Time: 1906

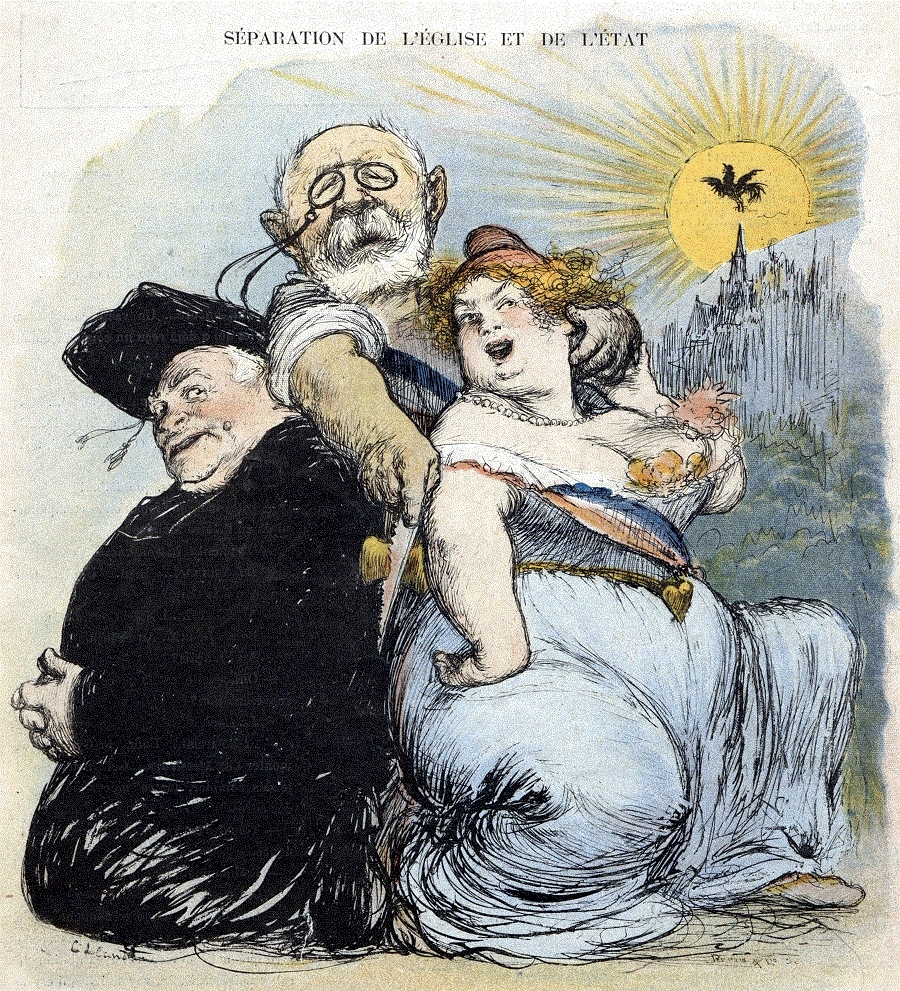

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Behind the acknowledged receipts of the Church and its open activities, was the vast army of the monastic orders, with their revenues, their palaces and fortresses, their estates, their farms, their manufactories and workshops. Richer, stronger, more numerous than they had ever been in their palmiest days, they maintained their spokesmen in parliament, their apologists and bravoes on the press, and stood ready to support anyone and everyone who threatened the republic. Their property was tax-free, their members and their acolytes exempt from conscription. While the body of the nation bent under the terrible load of reconstruction, of renewing its plant and stock, of rebuilding its balance, after the destruction and waste of the war, they stood aside, intent on their own strength, taking advantage of every opportunity to add to their possessions or their privileges, and rendering as little as possible in return.

The most pressing danger to the republic lay in the clerical monopoly of public education. For France to recover her national life, to be able to look forward to a stable administration, it was absolutely necessary to take the elementary school out of the hands of the priest, the university out of those of the episcopate. This could not be done at once, but by 1879 it was possible for Jules Ferry to carry his bill for reorganization of the Conseil Supérieur de l’Enseignement Public and the Conseils Académiques. This eliminated the clerical element introduced by the Loi Falloux. The appointment and promotion of tutors and professors at the universities, of teachers in the schools, was restored to the State. Students in ” free ” colleges must henceforth take their degrees at the hands of the State, and the right of opening, managing, or teaching, in a “free” school was taken away from all members of an unauthorized body. It was Jules Ferry again who brought about the law of 1882, laicizing elementary education, and making it free as well as compulsory.

From this reform dates the steady growth of the republican vote, accompanied by an increasing cult of the open air. The spread of manly games and exercises among schoolboys and students has paralleled and illustrated their emancipation from monkish rule and method, their growing desire and aptitude for independence, their belief in and reliance on themselves. Year by year the recruits who come up for the army mark an advance upon their predecessors, and year by year as they pass from the ranks to the people they vote more and more as they think, and less and less as anyone bids them. That they have lost much may be true, but they have gained themselves.

I have taken this question of education out of its order of date, for the sake of its importance in understanding things as they are. We must now turn back to May, 1877, for a typical instance of the interference of Rome in French politics, and a crucial episode in the fight we are following.

The Italian Parliament had passed a law regulating certain clerical abuses and roused the Vatican to anger. The pope denounced the law as persecution of the Church and ordered the episcopate everywhere to bring pressure to bear on their respective Governments in favor of his injured power. Acting under his instructions, the French bishops laid their charges (mandements) before the Government. The Bishop of Nîmes announced that “the temporal power of the pope will arise again after earthquakes in which many armies and several crowns may be swallowed up.” The Bishop of Nevers wrote to Marshal MacMahon begging him “to link up again the ancient chain of the traditions of our France,” and to “resume his place as the eldest son of the Church”. Copies of this letter was sent to every mayor throughout the diocese of Nevers, with a demand for his official aid in the movement organized by the bishops. The agitation was carried into parliament by the Clericals and Royalists, who were beaten after a fierce debate, ending in a vote which declared that “the Ultramontane manifestations, of which the repetition may endanger the internal and external security of the country, constitute a flagrant violation of the rights of the State,” and called upon the Government to “repress this antipatriotic movement by all the legal means in its power.”

Up to this time, any attack upon the concordat had come from the side of the Church; in this debate it was plainly stated by the republicans that they would henceforth accept and respect the concordat only in so far as it was recognized to be a bilateral contract, binding upon the Church to the same extent as upon the State. The answer of the Church was its part in the Boulangist movement.

Another crucial point in the relations of Church and State was reached on the 11th and 12th of December, 1891, in the debate provoked by the manifestation of the French pilgrims at Rome in honor of “the pope-king.” For the last time, the Church could provoke an open conflict in the hope of victory, but after two days of fierce discussion the Chamber voted by 243 to 223 that the Government should use all the powers it possessed, and all that it might find necessary to demand from parliament, in defense of the public peace. It was during this debate that the threat of separation was made use of. Speaking of the claim that the Church in the persons of the bishops and archbishops stood above the law, the Prime Minister, M. de Freycinet, said that the claim was preposterous (renversante):

The bishops, I imagine, are French citizens. If they cannot accept the existing laws, why do they seek to be bishops? We desire to live in peace, but not at the price of being dupes. The present Ministry does not regard itself as having received a mandate from the country to bring about the separation of Church and State, nor even to prepare for it. But we have received a mandate to defend the State, and if separation should result from the agitation that has been started, the responsibility will lie with its authors, and not with us.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Emile Combes begins here. John Ireland begins here. Henry H. Sparling begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.