This series has three easy 5-minute installments. This first installment: South Sea Company Forms.

Introduction

Before the Roaring Twenties in America and the subsequent stock market crash of 1929 there was the bubbles of the tens of the eighteenth century. Another selection covers the financial bubble in France. This one covers the one in Great Britain which lasted less than one year.

This selection is from The Mississippi Bubble – A Memoir of John Law by Louis Adolphe Thiers published in 1859. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Louis Adolphe Thiers (1797-1877) was President of the French Republic who fixed France’s finances after the Franco-Prussian War.

Time: 1720

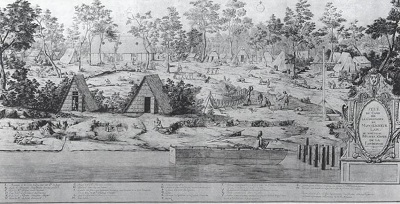

Public domain image from Wikipedia

The South Sea Company was originated by the celebrated Harley, Earl of Oxford, in the year 1711, with the view of restoring public credit, which had suffered by the dismissal of the Whig ministry, and of providing for the discharge of the army and navy debentures and other parts of the floating debt, amounting to nearly ten millions sterling. A company of merchants, at that time without a name, took his debt upon themselves, and the government agreed to secure them for a certain period the interest of 6 per cent. To provide for this interest, amounting to six hundred thousand pounds per annum, the duties upon wines, vinegar, India goods, wrought silks, tobacco, whale-fins, and some other articles were rendered permanent. The monopoly of the trade to the South Seas was granted, and the company, being incorporated by act of Parliament, assumed the title by which it has ever since been known. The minister took great credit to himself for his share in this transaction, and the scheme was always called by his flatterers “the Earl of Oxford’s masterpiece.”

Even at this early period of its history the most visionary ideas were formed by the company and the public of the immense riches of the eastern coast of South America. Everybody had heard of the gold and silver mines of Peru and Mexico; everyone believed them to be inexhaustible, and that it was only necessary to send the manufactures of England to the coast to be repaid a hundred-fold in gold and silver ingots by the natives. A report industriously spread, that Spain was willing to concede four ports on the coasts of Chile and Peru for the purposes of traffic, increased the general confidence, and for many years the South Sea Company’s stock was in high favor.

Philip V of Spain, however, never had any intention of admitting the English to a free trade in the ports of Spanish America. Negotiations were set on foot, but their only result was the assiento contract, or the privilege of supplying the colonies with negroes for thirty years, and of sending once a year a vessel, limited both as to tonnage and value of cargo, to trade with Mexico, Peru, or Chile. The latter permission was only granted upon the hard condition that the King of Spain should enjoy one-fourth of the profits, and a tax of 5 per cent. on the remainder. This was a great disappointment to the Earl of Oxford and his party, who were reminded, much oftener than they found agreeable, of the

Parturiunt montes, nascitur ridiculus mus.“

But the public confidence in the South Sea Company was not shaken. The Earl of Oxford declared that Spain would permit two ships, in addition to the annual ship, to carry out merchandise during the first year; and a list was published in which all the ports and harbors of these coasts were pompously set forth as open to the trade of Great Britain. The first voyage of the annual ship was not made till the year 1717, and in the following year the trade was suppressed by the rupture with Spain.

The name of the South Sea Company was thus continually before the public. Though their trade with the South American states produced little or no augmentation of their revenues, they continued to flourish as a monetary corporation. Their stock was in high request, and the directors, buoyed up with success, began to think of new means for extending their influence. The Mississippi scheme of John Law, which so dazzled and captivated the French people, inspired them with an idea that they could carry on the same game in England. The anticipated failure of his plans did not divert them from their intention. Wise in their own conceit, they imagined they could avoid his faults, carry on their schemes forever, and stretch the cord of credit to its extremist tension without causing it to snap asunder.

It was while Law’s plan was at its greatest height of popularity, while people were crowding in thousands to the Rue Quincampoix, and ruining themselves with frantic eagerness, that the South Sea directors laid before Parliament their famous plan for paying off the national debt. Visions of boundless wealth floated before the fascinated eyes of the people in the two most celebrated countries of Europe. The English commenced their career of extravagance somewhat later than the French; but as soon as the delirium seized them, they were determined not to be outdone.

Upon January 22, 1720, the House of Commons resolved itself into a committee of the whole house to take into consideration that part of the King’s speech at the opening of the session which related to the public debts, and the proposal of the South Sea Company toward the redemption and sinking of the same. The proposal set forth at great length, and under several heads, the debts of the state, amounting to thirty million nine hundred eighty-one thousand seven hundred twelve pounds, which the company was anxious to take upon itself, upon consideration of 5 percent. per annum, secured to it until midsummer, 1727; after which time the whole was to become redeemable at the pleasure of the legislature, and the interest to be reduced to 4 percent. It was resolved, on February 2nd, that the proposals were most advantageous to the country. They were accordingly received, and leave was given to bring in a bill to that effect.

Exchange Alley was in a fever of excitement. The company’s stock, which had been at 130 the previous day, gradually rose to 300, and continued to rise with the most astonishing rapidity during the whole time that the bill in its several stages was under discussion. Sir Robert Walpole was almost the only statesman in the House who spoke out boldly against it. He warned them, in eloquent and solemn language, of the evils that would ensue. It countenanced, he said,

the dangerous practice of stock-jobbing, and would divert the genius of the nation from trade and industry. It would hold out a dangerous lure to decoy the unwary to their ruin, by making them part with the earnings of their labor for a prospect of imaginary wealth. The great principle of the project was an evil of first-rate magnitude; it was to raise artificially the value of the stock by exciting and keeping up a general infatuation, and by promising dividends out of funds which could never be adequate to the purpose.”

The bill was two months in its progress through the House of Commons. During this time every exertion was made by the directors and their friends, and more especially by the chairman, the noted Sir John Blunt, to raise the price of the stock. The most extravagant rumors were in circulation. Treaties between England and Spain were spoken of whereby the latter was to grant a free trade to all her colonies; and the rich produce of the mines of Potosi-la-Paz was to be brought to England until silver should become almost as plentiful as iron. For cotton and woolen goods, which could be supplied to them in abundance, the dwellers in Mexico were to empty their golden mines. The company of merchants trading to the South Seas would be the richest the world ever saw, and every hundred pounds invested in it would produce hundreds per annum to the stockholder. At last, the stock was raised by these means to near 400, but, after fluctuating a good deal, settled at 330, at which price it remained when the bill passed the Commons by a majority of 172 against 55.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.