Today’s installment concludes The South Sea Bubble Bursts,

our selection from The Mississippi Bubble – A Memoir of John Law by Louis Adolphe Thiers published in 1859.

If you have journeyed through the installments of this series so far, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of three thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The South Sea Bubble Bursts.

Time: 1720

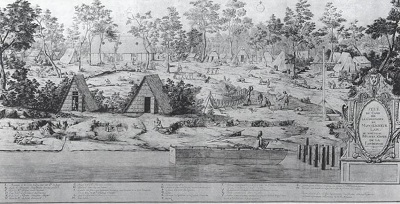

Public domain image from Wikipedia

It is time, however, to return to the great South Sea gulf, that swallowed the fortunes of so many thousands of the avaricious and the credulous. On May 29th the stock had risen as high as 500, and about two-thirds of the government annuitants had exchanged the securities of the state for those of the South Sea Company. During the whole of the month of May the stock continued to rise, and on the 28th it was quoted at 550. In four days after this it took a prodigious leap, rising suddenly from 550 to 890. It was now the general opinion that the stock could rise no higher, and many persons took that opportunity of selling out, with a view of realizing their profits. Many noblemen and persons in the train of the King, and about to accompany him to Hanover, were also anxious to sell out. So many sellers and so few buyers appeared in the alley on June 3rd that the stock fell at once from 890 to 640. The directors were alarmed and gave their agents orders to buy. Their efforts succeeded. Toward evening confidence was restored, and the stock advanced to 750. It continued at this price with some slight fluctuation, until the company closed its books on June 22nd.

It would be needless and uninteresting to detail the various arts employed by the directors to keep up the price of stock. It will be sufficient to state that it finally rose to 1000. It was quoted at this price in the commencement of August. The bubble was then full-blown and began to quiver and shake preparatory to its bursting.

Many of the government annuitants expressed dissatisfaction against the directors. They accused them of partiality in making out the lists for shares in each subscription. Further uneasiness was occasioned by its being generally known that Sir John Blunt, the chairman, and some others had sold out. During the whole of the month of August the stock fell, and on September 2nd it was quoted at 700 only.

Day after day it continued to fall, until it was as low as 400. In a letter dated September 13th, from Mr. Broderick, M.P., to Lord Chancellor Middleton, and published in Coxe’s Walpole, the former says:

Various are the conjectures why the South Sea directors have suffered the cloud to break so early. I made no doubt but they would do so when they found it to their advantage. They have stretched credit so far beyond what it would bear that specie proves insufficient to support it. Their most considerable men have drawn out, securing themselves by the losses of the deluded, thoughtless numbers, whose understandings have been overruled by avarice and the hope of making mountains out of mole-hills. Thousands of families will be reduced to beggary. The consternation is inexpressible — the rage beyond description, and the case altogether so desperate that I do not see any plan or scheme so much as thought of for averting the blow; so that I cannot pretend to guess what is next to be done.”

Ten days afterward, the stock still falling, he writes:

The company have yet come to no determination, for they are in such a wood that they know not which way to turn. By several gentlemen lately come to town, I perceive the very name of a South Sea man grown abominable in every country. A great many goldsmiths are already run off, and more will; daily I question whether one-third, nay, one-fourth, of them can stand it.”

At a general court of the Bank of England, held soon afterward, the governor informed them of the several meetings that had been held on the affairs of the South Sea Company, adding that the directors had not yet thought fit to come to any decision upon the matter. A resolution was then proposed, and carried without a dissentient voice, empowering the directors to agree with those of the South Sea to circulate their bonds to what sum and upon what terms and for what time they might think proper. Thus both parties were at liberty to act as they might judge best for the public interest.

Books were opened at the bank for subscription of three millions for the support of public credit, on the usual terms of 15 pounds percent. deposit, 3 pounds percent. premium, and 5 pounds percent interest. So great was the concourse of people in the early part of the morning, all eagerly bringing their money, that it was thought the subscription would be filled that day; but before noon the tide turned. In spite of all that could be done to prevent it, the South Sea Company’s stock fell rapidly. Its bonds were in such discredit that a run commenced upon the most eminent goldsmiths and bankers, some of whom, having lent out great sums upon South Sea stock, were obliged to shut up their shops and abscond. The Sword-blade Company, which had hitherto been the chief casher of the South Sea Company, stopped payment. This, being looked upon as but the beginning of evil, occasioned a great run upon the bank, which was now obliged to pay out money much faster than it had received it upon the subscription in the morning. The day succeeding was a holiday (September 29th), and the bank had a little breathing-time. It bore up against the storm; but its former rival, the South Sea Company, was wrecked upon it. Its stock fell to 150, and gradually, after various fluctuations, to 135.

The bank, finding it was not able to restore public confidence and stem the tide of ruin, without running the risk of being swept away, with those it intended to save, declined to carry out the agreement into which it had partially entered. “And thus,” to use the words of the Parliamentary History, “were seen, in the space of eight months, the rise, progress, and fall of that mighty fabric, which, being wound up by mysterious springs to a wonderful height, had fixed the eyes and expectations of all Europe, but whose foundations, being fraud, illusion, credulity, and infatuation, fell to the ground as soon as the artful management of its directors was discovered.”

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on The South Sea Bubble Bursts by Louis Adolphe Thiers from his book The Mississippi Bubble – A Memoir of John Law published in 1859. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on The South Sea Bubble Bursts here and here and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.