When France fell to pieces, during the Franco-Prussian War, the Church was the sole organization left unshaken.

Continuing France Separates Church and State,

Today we begin the third part of the series with our selection from special article to Great Events by Famous Historians, volume 20 by Henry H. Sparling published in 1914. The selection is presented in 3 easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Henry H. Sparling (1860-1924) was a Socialist journalist from Great Britain.

Previously in France Separates Church and State.

Time: 1906

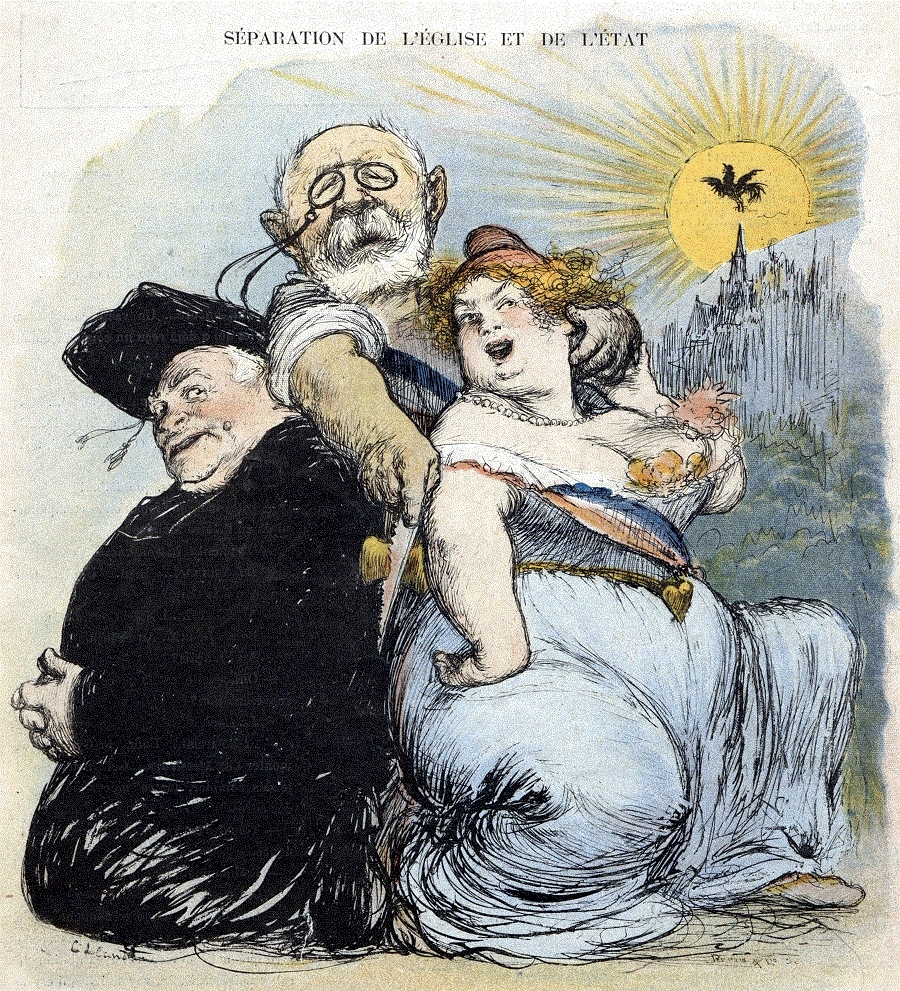

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

It is necessary to go back at least to the time of the Franco-Prussian War, if we are to disentangle the accusations and contradictions of the day and approach the problem of Church and State in France with any real chance of understanding it. If we do so, we shall find that the present dead lock is not the outcome of any anti-Christian, or even anti Catholic, feeling on the part of the French Government or any important part of the French people, but the inevitable outcome of two historic forces — the claim of the papacy that the Church in France is that of Rome and free of French law, the claim of the State that the Church in France is but a department of French activity and subject as such to national control. Another phase, in short, of the quarrel that has convulsed Christendom for centuries.

When France fell to pieces, during the Franco-Prussian War, the Church was the sole organization left unshaken. Army, administration, the whole Governmental machine, had been shattered and torn into fragments, but the Church was stronger than ever. For one thing, because of the proclamation and acceptance of papal infallibility a few months before, and for another because of the confusion amid which she moved. After the 18th of July, 1870, the pope stood isolated and supreme, his power no longer tempered by that of the princes of the Church, a bishop no more able to stand against him than a begging friar.

This triumph of Ultramontanism, or Roman power, after a struggle which had lasted for centuries, going back to the Isidorian Decretals and beyond, meant much to the newly formed republic. It meant that France was occupied by a foreign army, which could not be bought out as that of Ger many had been. The episcopate in France was henceforth Roman, with no room in its ranks for a Hincmar of Reims, for a William of Paris, nor even for a Bossuet. From the highest to the lowest, every member of the hierarchy could only think and act as Frenchmen so far as the policy of the if Church allowed, and the policy of the Church must be that of Rome, of the pope and his camarilla.

At every turn of the road toward complete self-government, the French people were to find the Church as an enemy, more or less masked; to do it justice, less often masked than not. Had it covered its movements a little more carefully, chosen its tools and stalking-horses with a little more skill and foresight, it is impossible to say how long the hold of Rome upon France -— “eldest daughter of the Church” and proud of the title in spite of everything — might not have lasted. As it is, over thirty years of ambuscades, of mine and pitfall, of open fight, have been necessary before France could be aroused to assert herself, to recognize the real extent of her danger, and set out in earnest to eradicate it. Even now, the pope or his advisers would but accept the silver bridges that everyone is ready to build for them, a working arrangement could be come to. But as Rome was, so Rome is, and ever will be. And the 14th of July, 1789, is less evil in her memory than the 7th of July, 1438, the day of the Pragmatic Sanction, in which the rights of the Gallican Church were asserted in opposition to the usurpations of the pope.

But to return to 1870. The Church was well-nigh all powerful, would have been so beyond question had not papal infallibility been too new for the pope to trust his weapons. To a lesser degree he suffered in the same way as the republicans, from being forced to work through men who had been trained and formed under another system. But he was the quicker to get his team in hand, and in 1873 could score his first goal. Even before that he had scored a try. In the midst of the crisis through which France was passing, while the National Assembly was straining every nerve to bring order out of confusion, to pay out the Prussians, reorganize the army, patch up the administration, obtain a qualified obedience-fidelity was too much to hope for — from the servants of the nation, the bishops demanded the restoration of the temporal power, and were only outmaneuvered by M. Thiers, who dodged and evaded the crucial vote. The 24th of May, 1873, was a sweeping victory for the Church, which made one mistake, however, and that a fatal one; for MacMahon was an honest man, and a soldier before all.

The Church held everything in her hand, and the Church was Rome. That is the refrain that recurs incessantly. The strife is not and never has been against religion in itself, not even against Catholicism, but against the domination of Rome. In the Budget for 1873 the Church figured for 49,000, ooo fcs., as against 36,000,000 fcs. for education; from the local taxation of the departments and the communes she received 31,000,000 fcs. Her part of the national revenues for that year, therefore, was eighty millions of francs, and the amount was rising year by year. Public education was entirely under her thumb; the Conseil Supérieur was formed of bishops and archbishops, and on every Conseil Départemental they were in the majority. Teachers were appointed and dismissed on their merits as Churchmen. Armed with the law of 1850, the notorious Loi Falloux, every village priest could supervise the teaching in his school, and see that religious instruction came before all else. The priest was everywhere, in control of the Assistance Publique, the hospitals and infirmaries, the prisons, the barracks, on every man-of-war. The army was at his beck and call, to fill out his processions, lend him guns and flags for his fêtes, to consult him as to promotion, even as to the amount and quality of the obedience to be rendered to the civil powers.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Emile Combes begins here. John Ireland begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.