Separation of the Church from the State in America means liberty and justice; there it means servitude and oppression.

Continuing France Separates Church and State,

with a selection from Sermon on the French Church by John Ireland published in around 1906. This selection is presented in 3.7 installments, each one 5-minutes long. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in France Separates Church and State.

Time: 1906

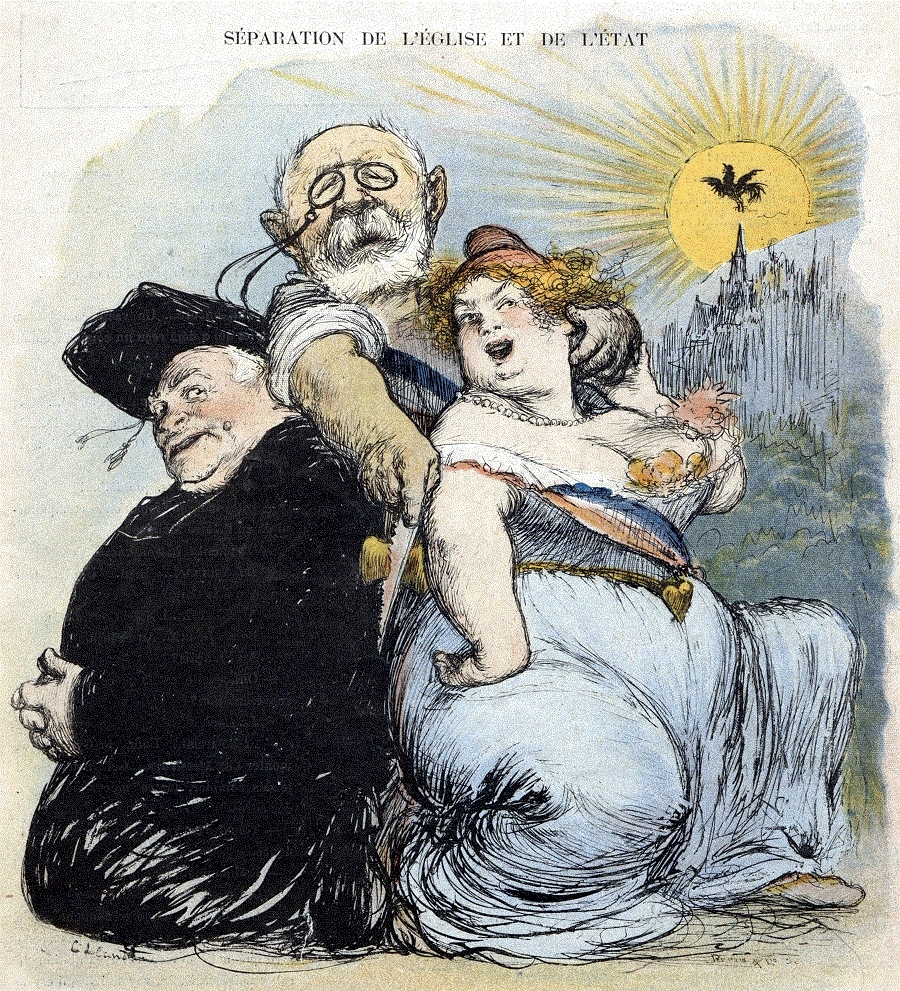

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Annual stipends were to be paid to bishops and priests. The promise of those stipends was no gratuity on the part of the State. It was a restitution of values taken by the State from the Church. The concordat simply reinsures the obligation by which the “constituent assembly” in 1789 held itself bound when it placed the properties of the Church “at the disposition of the nation.” Its words were:

All ecclesiastical properties are put at the disposition of the nation, with the obligation resting thereon to provide in a becoming manner for the expenses of the public worship, the maintenance of the clergy, the relief and succor of the poor and destitute.”

Stipends paid in France to the clergy, it must be clearly understood, were never a gift from the national treasury to the Church. They were the payment of a debt, a partial restitution for properties once confiscated and not afterward restored to the Church. The properties that were restored in 1801 were only a fraction of those originally confiscated in 1789.

By the concordat Napoleon wrested a high price for the concessions he was willing to make to the Church. But it was a vast gain over the preceding situation, and the Church gladly resigned herself to the sacrifice. With the concordat the Church at least knew where she stood; she had legal rights to which she could appeal; she was secure in the possession of her temples; her bishops and priests were housed beneath their own roofs; the essential life of her organism remained intact; she could live and work.

And now, by act of parliament, the concordat is abolished; a régime of separation is instituted. Let not Americans be misled by words which have a totally different signification in this land from what is allowed them in France. Separation of the Church from the State in America means liberty and justice; there it means servitude and oppression.

Speaking to the cardinals present in the Vatican, Pius X. said of the French situation:

We are ready to submit to separation from the State, but it must be a fair separation such as obtains in the United States, in Brazil, in Great Britain, in Holland — and not a subjection.”

No Catholic in the United States makes objection to separation, for here separation means exactly what it purports to mean.

Far different is the law of separation in France. It has its good points, for which we praise it. It restores to the Church the precious liberty of naming her bishops and her parish priests without interference whatsoever on the part of the civil authority. But it has its evil points, and these it is of which the Church makes complaint.

The specific gravamen of the French law of separation is the so-called “associations of worship” or civil corporations, to be organized for the holding and the administration of ecclesiastical properties.

The importance to the Church of a proper control of her properties is easily understood. It is a question of her houses of worship, of the residences of her bishops and of her priests, of her seminaries for the education of her clergy. She does not live or work in the air; she lives and works upon the hard earth, and if there, where her feet rest, she is not free and independent, it is vain to preach to her that the free exercise of her worship is guaranteed to her. The proposed “associations of worship” do not secure to her the sufficient control of her properties; they do not accord to her liberty and justice.

A recent note from the Vatican formulates the case against the French associations.

The law confers on cultural associations rights which not only belong to the ecclesiastical authorities in the practice of worship and in the possession and administration of ecclesiastical property, but the same associations are rendered independent of the ecclesiastical hierarchy, and instead are placed under the jurisdiction of the lay authorities.”

The Catholic Church is essentially and vitally hierarchical; it is ruled, first, by the pontiff of Rome, next by the bishop of the diocese. In the “associations of worship” there is no guaranty given that the hierarchical principles of the Church shall be allowed to enter into function. Indeed, they are explicitly excluded by article VIII of the law, which, dealing with cases of rival associations claiming to represent the one and same parish, allows the Council of State to decide the issues without reference whatever to papal or episcopal jurisdiction. And so, an association of worship owning and controlling temple and presbytery, receiving and disbursing revenues, is able, if it so wishes, so far as the law goes, to put aside priests, bishops, and pope, to conduct and regulate as it likes public worship subject only in final appeal to the Council of State. Never will the Catholic Church agree to lodge possession of her temporalities or the regulation of her worship in associations independent of her hierarchy. She is what her condition makes her; and where liberty is professed in her regard, she must be allowed to live as her constitution dictates.

There is another objection to the law of separation and the formation of associations of worship. The law sets out with acts of positive spoliation. It suppresses the annual allowances heretofore made to bishops and to priests. Those allowances were never, as we have seen, a gift from the national treasury. They were payments of a debt in return for the properties confiscated by the “constituent assembly.” It would not, I know, have been difficult to obtain from the Church a renunciation of these allowances. But it was simplest justice on the part of the State to propose to the Church some sort of compensation for the loss she was to sustain, or at least to petition for her assent to the sacrifice she was expected to make. And next — and this is a far more serious matter -— the law assumes that the State is the undisputed owner of all properties confiscated in 1789, and put back to the disposition of the bishops in 1801. All such properties are taken over for good by the State. Cathedrals and other houses of worship are to be used by the Church as tenant at will; episcopal and parochial residences and seminary buildings are within two, or at the most five, years to be vacated by their present occupants, and then to be returned unreservedly to the State. This is confiscation of the blackest dye — and the Church owed it to herself to refrain from any act or attitude that should openly or impliedly seem to ratify it.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Emile Combes begins here. John Ireland begins here. Henry H. Sparling begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.