Politics, more especially international policy, are, however, not altogether a legal process; it is preeminently an historical one.

Continuing Austria-Hungary Annexes Bosnia-Herzegovina,

with a selection from Crisis in the Near East by Emil Reich published in around 1908. This selection is presented in 5.5 easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Austria-Hungary Annexes Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Time: 1908

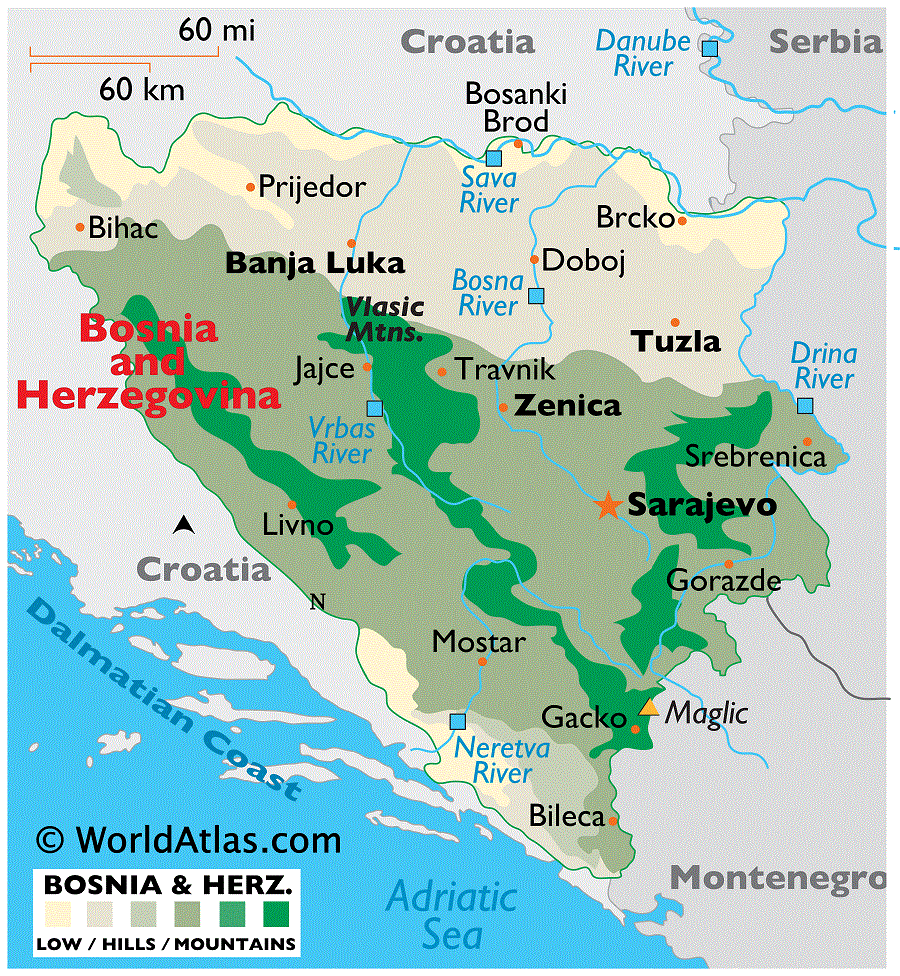

Place: Bosnia-Herzegovina

The same quality does not, however, attach to countries in the southeast of, or outside, Europe. In those parts of the world the conflicting interests of the dominating European Powers have up to very recent times found it almost impossible to promote the crystallization of political relations in forms of definite, clear-cut, and unequivocal outlines. All the contrivances by means of which Western and Central Europe used, in the fifteenth, sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries, to patch up differences between States and nations, between denominations and sects, or dynasties and peoples, and which contrivances have since the French Revolution been either in abeyance or radically removed; all these enclaves, “public or international servitudes,” “constitutional fictions,” and inarticulate “arrangements” of political problems have of necessity been the order of the day in the Balkans. Politics, more especially international policy, are, however, not altogether a legal process; it is preeminently an historical one. Thus, in the present case, it can not possibly be denied that, while the above temporary contrivances and fictions had their complete raison d’être as long as the political life of the Balkan nations was in a state of backwardness, they can no longer be held to fulfil a useful function at a time when the political maturity which in Central and Western Europe has caused their disappearance has at last reached the Balkan Peninsula too. In one word, the Balkans, too, have arrived at that stage of political life when crystallization in forms of unequivocal outlines becomes a matter of urgent necessity. Fictions will no longer do; patched-up compromises and obnoxious servitudes can no longer be endured. Those temporary contrivances have outlived themselves and bring the nations still enduring them into a constantly increasing maze of impasses.

This is precisely what has happened in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The position of Austria-Hungary in the two provinces “occupied” by her became, as a matter of fact, almost unbearable. As invariably happens in such cases, Austria Hungary was placed between two evils, and had to decide which of the two was, if submitted to, the lesser of the two. One evil was an unavoidable conflagration in and around the two provinces, owing to the constant intrigues and smoldering revolt of the Southern Slavs, principally the Serbians, who hoped to avail themselves of the false position and legally fictitious sovereignty of Austria-Hungary in Bosnia and Herzegovina for the purpose of a sort of Pan-Serbianism. Of these very serious intrigues I will at once give the requisite data from official and partly unpublished sources. At present we shall briefly indicate the second evil hinted at above. It consisted in a formal incorrectness, which did not entail any substantial damage on any of the non-Turkish nations in the Balkans, nor on the Great Powers, and which conferred upon the most interested party, on the Turks proper, a considerable advantage. This formal incorrectness was the declaration by Austria-Hungary, made on the 7th of October last, to the effect that she annexed the two provinces; or, in other words, that she named her actual and complete sovereignty by its true name.

It is quite alien to the purpose of this article to attempt denying that in the action of Austria-Hungary there was an element of formal incorrectness toward the Powers who had, in Article XXV. of the Berlin Treaty, entrusted Austria Hungary with the occupation and complete administration of the two provinces. It is not contended that if a previous effort had been made to obtain the consent of the Powers the procedure would have been more incorrect. On the contrary, the procedure would, in that case, have been formally more correct. Nor is it here meant to use the tu quoque argument, for which the history of all the Great Powers concerned supplies more than a goodly number of precedents. It is even not intended to press the well-known tacit condition of all international treaties, the clause rebus sic stantibus, to its finest ramifications. All that it is here meant to state is this, that Austria-Hungary found herself in the course of the last two years in a condition of what is commonly called force majeure, in consequence of which she was compelled to choose the lesser evil, as the one that was most likely to bring about the desired improvement not only fully, but also as speedily as no other procedure, least of all an international conference, can ever bring about.

It is now necessary to give a full statement of the facts which placed Austria-Hungary in the position of being under the pressure of force majeure over two years before the new régime in Turkey proper profoundly altered the entire political aspect of the Balkans. All of those facts come back to the indubitable, well-organized, and most dangerous attempts of the Serbians and Croatians to oust Austria-Hungary from Bosnia and Herzegovina. To the English reader, to whom Serbia or Croatia appears merely as small fry, such attempts and efforts on the part of a little nation against a great Power do not seem to be invested with much importance. However, a very short reflection of how these factors are constituted in reality will induce even a casual observer to view Serbian and Croatian intrigues and agitation in Austria-Hungary in quite a different light.

Croatia, Slavonia, Styria, and Carinthia, let alone Istria, or, in other words, entire provinces of Austria-Hungary, are teeming with several millions of Southern Slavs who talk practically the same language with their immediate neighbors, the inhabitants of Bosnia, Herzegovina, and Serbia. If we add the very numerous Serb-speaking population of the south of Hungary proper, we may safely state the remarkable fact that the whole south of Austria-Hungary is in its vastly preponderating majority a mass of people who naturally, and still more in consequence of continuous and active propaganda, deeply sympathize with the political aspirations of the Slavs in Serbia and in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and even in Montenegro.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Emil Reich begins here. Major Archibald Colquhoun begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.