The Church can never be uprooted from the soil of France; the attempt was often before made; it always failed.

Continuing France Separates Church and State,

with a selection from Sermon on the French Church by John Ireland published in around 1906. This selection is presented in 3.7 installments, each one 5-minutes long. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in France Separates Church and State.

Time: 1906

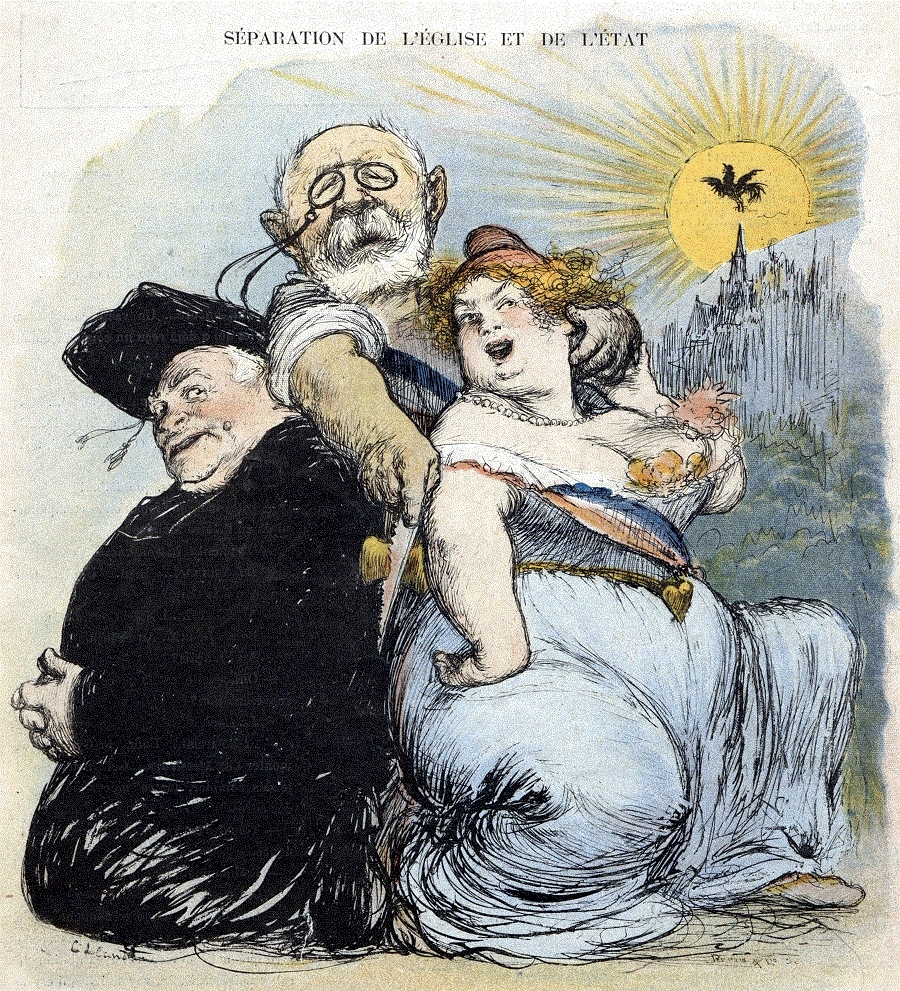

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Combine together in the present Government of France the idea of deep-seated hatred of religion and that of the omnipotence of the State, and you can understand how the law of separation, with its associations of worship, has come to be enacted.

Let us understand, however, what is meant by the Government, lest we believe things to be worse than they are. The law of separation was carried in the chamber of deputies by a vote of 341 against 233, and in the senate by a vote of 181 against 102. It would not have required a very marked change in membership, either of the chamber or of the senate, to have defeated the law. Sound sense and a respect for rights cover yet many benches in the French parliament, and no wonder were it if someday soon it claimed supremacy.

What is the matter with France? Why do there come from the voting-urns of France anti-Catholic majorities in parliament?

France is a Catholic country; of this we must not doubt. Infidelity has made its inroads among her people; the test of active faith, attendance at mass and the reception of the sacraments, is wanting among many. But their hearts are loyal to the old religion and summoned to take their stand around the banner of the Church, the millions will not hesitate. I know France from the channel to the Mediterranean; I know her cities and her villages; I know her people — her aristocracy, her bourgeoisie, and her peasantry —- and I know them to be Catholic. How, then, explain the political situation? There are several causes to be noted. The masses are not used to political life. For ages they were governed; they do not com prehend the art of governing. Put a party in power -— it names the hundreds of thousands of officials from the prefect of a department to the humblest schoolteacher, to the village constable; they obey the order from Paris; they speak to the crowds around them-crowds who read little, who think little; and the crowds obey the mandate. An independent self-argued suffrage has not entered into the popular life. Nor is there among the masses the ambition to gain political victory. Paris for a century and a half has ruled France; establish a new régime, monarchy or republic, in Paris this evening; the provinces awaken tomorrow morning monarchical or republican. It will require long years to decentralize power in France, to give to each citizen consciousness of personal independence, to obtain through universal suffrage a true expression of national will.

The peasantry of France is naturally apathetic for all things outside its field or family hearthstone. If it moves at all it is at the call of the loudest voice, in response to the liveliest agitation —- and the loudest and the liveliest are the professional agitators, or the self-interested officials. There is no other country where a well-organized and stirring fraction of the population can sway so easily the masses and impose upon them its will.

The clergy, who are the chief sufferers, are somewhat to blame. They, too, have retained, even at the altar and in the pulpit, the spirit of passive obedience inherited from old régimes. Admirable in teaching the catechism, in administering the sacraments —- they have never learned the virtues of public life, they have never quickened beneath the activities of the battlefield. Their example and their preaching left their disciples in the same passivity; they know nothing of the public defense of principles; saints before the altar, they are cowards before the electoral urn.

Then, French Catholics have been unfortunate in many of their leaders and spokesmen. These remain dreamers of the past, partisans of buried political régimes. If the masses of the people have learned any one thing, it is this -— that France is a republic, that they are republicans. But the monarchists are numerous, chiefly the old nobility, the most generous patrons of religion, and too many of the clergy who still read their politics in Bossuet and Massillon, who judge the republican form of government by the Jacobin republic of contemporary France. Here is the weakness of the Catholics of France — the Infidel, the Socialist, who solicits votes, cries out — the republic is in peril, no republican must cast his vote for a monarchist — even if that monarchist be otherwise the best and the purest of men, and the masses vote for the infidel or the socialist, in order that the republic survive, trusting in the republic to do in the long run what is most serviceable for France, or even for religion itself.

The war may not cease in a day; time is needed to still passion and dispel prejudice. But the moment will come when all will be well. The Church can never be uprooted from the soil of France; the attempt was often before made; it always failed. From every battle the Church arose brighter, purer, more enlightened —- and in the victory of the Church France saw her own victory. We will pray for France, and for the Church, and in a special manner we will pray for Pius X., the leader of the forces of religion; that wisdom and fortitude be ever given to him, that with his own eyes he see the triumph of religion in that land which, let us believe, will always be the eldest daughter of the Church.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Emile Combes begins here. John Ireland begins here. Henry H. Sparling begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.