Today’s installment concludes France Separates Church and State,

the name of our combined selection from Emile Combes, John Ireland, and Henry H. Sparling. The concluding installment, by Henry H. Sparling from special article to Great Events by Famous Historians, volume 20, was published in 1914.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed selections from the great works of eight thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in France Separates Church and State.

Time: 1906

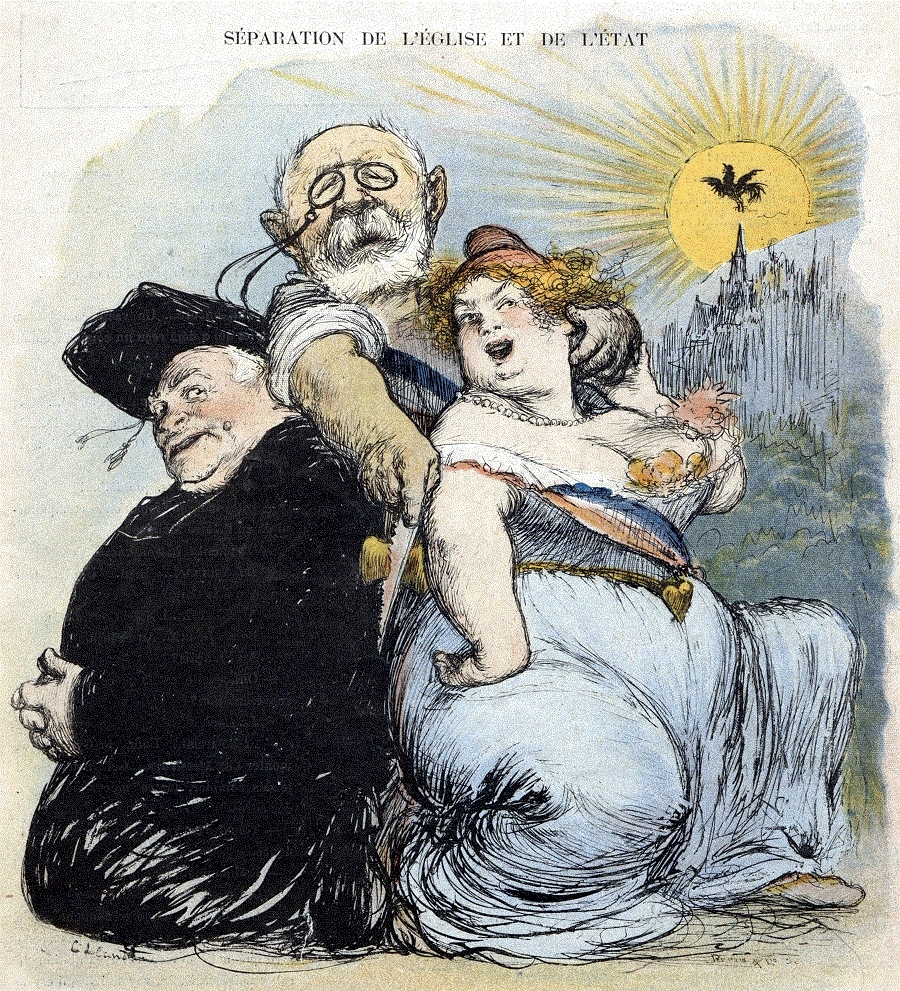

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The majority was a small one, but real, composed in large part of men who voted from a stern sense of duty, “with death in their hearts,” as one of them said. It was not in any sense a Radical majority, for the Extreme Left gave fifty-three votes to the Opposition. It meant that the country was tired of the Ultramontane agitation, that the average man, the solid middle-minded person, though no enemy of the Church in itself, was ready to fight Rome for national quiet, and that, however much he hesitated and temporized, he would fight hard if forced to do so.

We need but recall in passing how the Church acted throughout the Dreyfus affair and the Nationalist conspiracy. It was the revelations arising from these, however, that produced the Associations Law of 1901. Here, again, if it had not been for Ultramontanism, the Church might have remained unscathed. But to the Vatican, the salient fact was not that the bishops and monastic orders by accepting and applying the Law would recognize the supremacy of the State, but that in doing so they would be taking a first step on the road that might one day lead them to denying the supremacy of the pope. Hence the resistance that ensued, the fighting over the inventories, the attempt to procure a show of Russian intervention, the collective letter of seventy-two bishops and archbishops, and all the rest of it. Had the Vatican allowed, there was hardly a bishop or priest, excepting the Jesuits, who would not have accepted the Law and all its consequences.

Rome forbade, however, and the result was the Law of 1905, finally deciding the separation of Church and State, and relegating the Catholic Church to the position contentedly occupied by every other communion in the country. Again, and once more, in a more dangerous form than ever, that of congregationalism, Rome saw Gallicanism behind the new Law. If any parish might form itself into an association for the practice of its rites and defense of its belief, what other control than a moral one would remain to the Vatican? And Rome has never been satisfied to rely upon moral suasion.

The episcopate, or at least the vast majority thereof, and practically the whole of the parochial clergy, accepted the Law; with regret, perhaps, but with no open expression of discontent. It was fully understood by both bishop and priest that the associations cultuelles had been invented for the express purpose of safeguarding the rights of the Church, in so far as these were reconcilable with the safety of the State. And right throughout France they began to organize themselves, when Rome intervened once more. Behind the Encyclical of August 10, 1906, stands the Syllabus of December 8, 1864, of which it forms the development and application to the controversy of the day:

Accursed be he who shall say that the ecclesiastical power should not exercise its power without permission and assent of the State; that the Church has no right to employ force, or that she possesses no temporal power; that in case of a legal conflict between the Church and the State it is the civil law that should prevail; that the Church should be separated from the Church and the Church from the State; that the pope can or should reconcile himself to and compound with progress, Liberalism, and modern civilization.”

Hildebrand himself, nine hundred years ago, could have made no stouter claim to a universal theocracy centered in Rome, but France, though she be “the eldest daughter of the Church,” is now an emancipated female. A fact of which the elections of May last should have advised the Vatican would have done so but for the Jesuits and the monks who have closed round the pope and hold him prisoner of his ignorance.

Forced against their will to apply the Law, and anxious above all things that there should be no cry of persecution plausible enough to catch the ear of the average voter, the Government hastily drew up a supplementary Law to protect the Church against reprisals, to be feared wherever the priest had come into conflict with the municipality. So that, although all the buildings hitherto lent to the Church revert to the State or to the township, the churches with their furniture, decorations, and sacramental appliances are freely and fully at the disposal of the Church, and the liberty of public worship is absolutely maintained.

The present fight, then, as has already been said, is not an atheistic one against religion, nor even against Catholicism. It may have been, and almost certainly was, awaited by free thinkers with eagerness, but it has been provided for them by the Vatican and by nobody else. And they have played, as they will continue to play, a very small if active part in it. Rome, by her steadfast refusal of peace, her relentless attacks upon the civil power, her constant insolent intrusion upon matters of national administration and national defense, has roused the vast indifferent mass to protect itself and its business from foreign interference. The fight is that which was fought to a finish by England, safe behind her sea-frontier, some hundreds of years ago, and now that she is strong enough to face it, must be fought to a finish by France. Spain will take her turn tomorrow, and the United States —- paradoxical as it may sound —- the day after. The arrogant claim that priest and monk and bishop shall stand apart, above and beyond the common law, with more than a citizen’s privileges and none of his responsibilities, that the Church shall exist as a foreign body within the State, entitled to protection and support but rendering no allegiance in return, must in the long run be met and answered by every people desirous of preserving its corporate existence and possessing its soul alive.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our selections on France Separates Church and State by three of the most important authorities on this topic:

- Correspondence by Emile Combes published around 1906.

- Sermon on the French Church by John Ireland published in around 1906.

- special article to Great Events by Famous Historians, volume 20 by Henry H. Sparling published in 1914.

Emile Combes begins here. John Ireland begins here. Henry H. Sparling begins here.

This site features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on France Separates Church and State here and here and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.