The Church in France has always held that by those words the ownership of such ecclesiastical edifices was fully restored to the Church.

Continuing France Separates Church and State,

Today is our final installment from Emile Combes and then we begin the second part of the series with John Ireland. The selections are presented in eight easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in France Separates Church and State.

Time: 1906

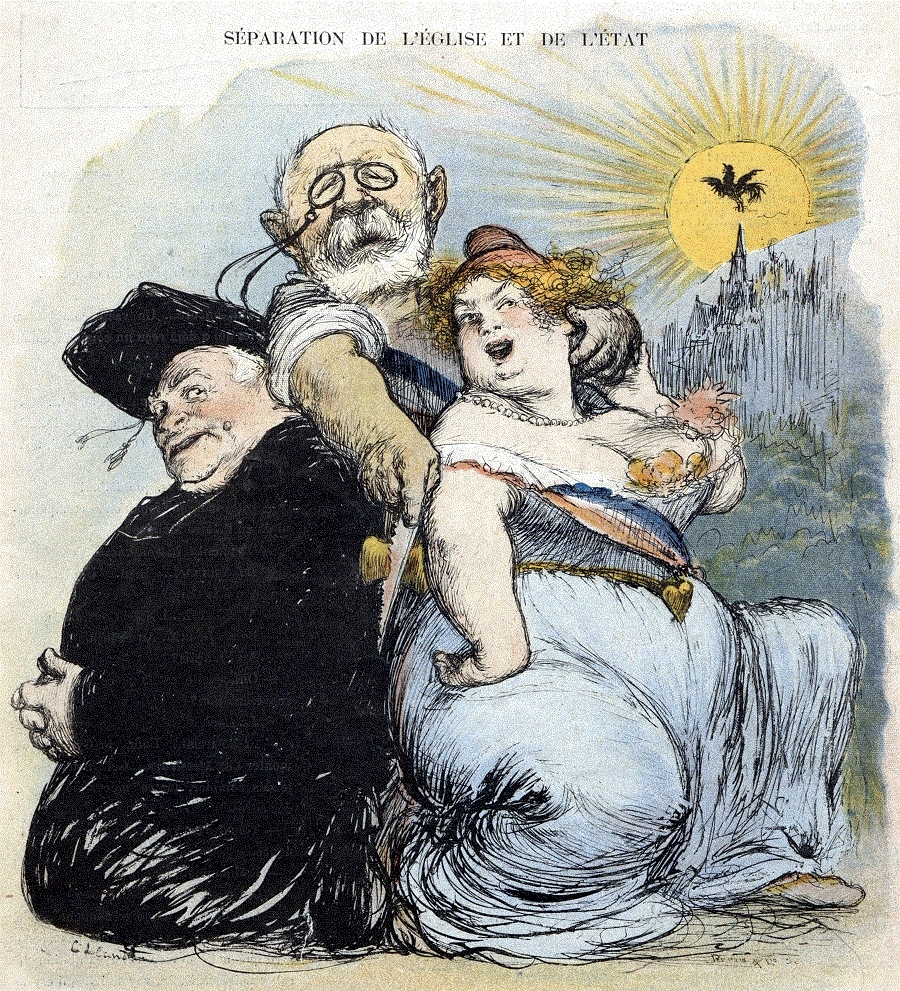

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The domestic policy of the Administration, financial and otherwise, defies the impartial critic; its foreign policy is a subject of envy and of admiration for the whole world. It is true, we do not look back upon the glory of battles as others do. We do not run after adventurous wars and colonial con quests. We have the modesty of thinking that it is true wisdom to utilize the conquered territories before thinking of aggrandizements. But above this there is the patriotic joy of proving that France has never enjoyed greater consideration and respect in the world. Her alliance and her friendship have never been more appreciated and sought after. Never has the freedom or the loyalty of her diplomats been more highly recognized. Never has her Prime Minister, inspired by the constant care for the peace of the world, been heard with more deference. To the pacific policy of this diplomacy the people testify with sincere joy, as assured pledges in bringing about universal peace. For, in spite of the alarms of war which sound from afar, peace remains our first need as our firm resolution.

Now we begin the second the second part of our series with our selection from Sermon on the French Church by John Ireland, The selection is presented in 3.7 easy 5-minute installments.

John Ireland (1838-1918) was a Catholic Cardinal in the United States.

The conflict raging at present between the Church and the State in France awakens universal and profound interest. It could not be otherwise, were it only for the personalities of the contestants. On one side, the Catholic Church, which for ages has swayed the moral and religious life of the tens of millions of mankind, and demands, as in Heaven’s name, the right to continue its work adown the coming ages; on the other, the “Grande Nation,” which, since the days of Clovis and of Charlemagne, has reveled in the title of “Eldest Daughter” of that Church, and has held so long amid all peoples the most conspicuous place in the vanguard of religion and of civilization.

We ask, What are the causes of the conflict? What are to be the results?

For the moment the situation is, undoubtedly, serious — serious for the one and for the other of the contestants. Yet, seen more anear, it reveals no coloring of despair, either for France or for the Church of France. A bright morning, I dare predict, will at a not distant time dawn over the field of battle, dropping from the skies sunshine and peace and begetting, both in the Church and in France, joy and exultation that the passage-at-arms, angry as it once was, has opened the way to a clearer understanding of mutual interests, to a warmer glow of olden mutual love.

The Catholic Church — of course, I love her and I champion her cause with delight. And France, too, I love. While I blame her, I shall not forget all that she has been during her storied centuries to mankind and to the Church, and I now bid my hearers to nurture no rancor against her. If I beckon her to defeat, it is that she rise from defeat greater and more glorious than victory could have made her.

The immediate incident leading to the conflict between the Church and the State in France was the law of separation, as it is called, ratified as a law of the land December 5, 1905. Since 1801 the relations between the Church and the State had been regulated by the concordat, or public pact, to which the first consul, Napoleon Bonaparte, and the Roman pontiff, Pius VII., had given their names. This concordat put an end to the persecutions of the revolution. By its terms the Catholic religion was acknowledged to be that of the great majority of the people of France; the free exercise of it was guaranteed; annual stipends were insured to its bishops and priests; churches, parochial residences, and other buildings intended for religious use, confiscated during the revolution and not afterward alienated by acts of the Government, were placed at the disposition of the bishops. In return the pontiff conceded that the first consul and his successors in power should have the right to nominate archbishops and bishops, to whom, however, canonical institutions should be given by the Roman pontiff, and agreed that only such priests should be appointed to the chief parishes as should be acceptable to the Government, and that neither he nor his successors should molest the holders of such ecclesiastical property confiscated by the revolution as had been alienated by the Government.

Two special observations on the terms of the concordat are of importance as bearing on the present conflict, one as to the disposition made of ecclesiastical properties, the other as to the stipends to be paid to bishops and to priests.

Churches, parochial residences, or other buildings intended for religious use, taken by the “constituent assembly” and not afterward alienated by acts of Government, were placed at the disposition of the bishops. The Church in France has always held that by those words the ownership of such ecclesiastical edifices was fully restored to the Church, which was now reinstated in the “status quo” existing before the revolution.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Emile Combes begins here. Henry H. Sparling begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.