A Company for carrying on an Undertaking of Great Advantage, but Nobody to know What It Is.”

Continuing The South Sea Bubble Bursts,

our selection from The Mississippi Bubble – A Memoir of John Law by Louis Adolphe Thiers published in 1859. The selection is presented in three easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in The South Sea Bubble Bursts.

Time: 1720

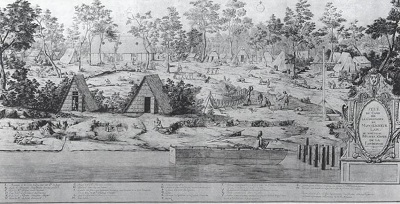

Public domain image from Wikipedia

Contrary to all expectation South Sea stock fell when the bill received the royal assent. On April 7th the shares were quoted at 310, and on the following day at 290. Already the directors had tasted the profits of their scheme, and it was not likely that they should quietly allow the stock to find its natural level without an effort to raise it. Immediately their busy emissaries were set to work. Every person interested in the success of the project endeavored to draw a knot of listeners round him, to whom he expatiated on the treasures of the South American seas. Exchange Alley was crowded with attentive groups. One rumor alone, asserted with the utmost confidence, had an immediate effect upon the stock. It was said that Earl Stanhope had received overtures in France from the Spanish government to exchange Gibraltar and Port Mahon for some places on the coast of Peru, for the security and enlargement of the trade in the South Seas. Instead of one annual ship trading to those ports and allowing the King of Spain 25 per cent. out of the profits, the company might build and charter as many ships as it pleased and pay no percentage whatever to any foreign potentate.

“Visions of ingots danced before their eyes,” and stock rose rapidly. On April 12th, five days after the bill had become law, the directors opened their books for a subscription of a million, at the rate of three hundred pounds for every one hundred pounds capital. Such was the concourse of persons of all ranks that this first subscription was found to amount to above two millions of original stock. It was to be paid in five payments, of sixty pounds each for everyone hundred pounds. In a few days the stock advanced to 340, and the subscriptions were sold for double the price of the first payment. To raise the stock still higher it was declared in a general court of directors, on April 21st, that the midsummer dividend should be 10 per cent., and that all subscriptions should be entitled to the same. These resolutions answering the end designed, the directors, to improve the infatuation of the moneyed men, opened their books for a second subscription of a million, at 4 percent. Such was the frantic eagerness of people of every class to speculate in these funds that in the course of a few hours no less than a million and a half was subscribed at that rate.

In the meantime, innumerable joint-stock companies started up everywhere. They soon received the name of “bubbles,” the most appropriate that imagination could devise. The populace are often most happy in the nicknames they employ. None could be more apt than that of “bubbles.” Some of them lasted for a week or a fortnight, and were no more heard of, while others could not even live out that short span of existence. Every evening produced new schemes and every morning new projects. The highest of the aristocracy were as eager in this hot pursuit of gain as the most plodding jobber in Cornhill. The Prince of Wales became governor of one company and is said to have cleared forty thousand pounds by his speculations. The Duke of Bridgewater started a scheme for the improvement of London and Westminster, and the Duke of Chandos another. There were nearly a hundred different projects, each more extravagant and deceptive than the other. To use the words of the Political State, they were “set on foot and promoted by crafty knaves, then pursued by multitudes of covetous fools, and at last appeared to be, in effect, what their vulgar appellation denoted them to be — bubbles and mere cheats.” It was computed that near one million and a half sterling was won and lost by these unwarrantable practices, to the impoverishment of many a fool and the enriching of many a rogue.

Some of these schemes were plausible enough and, had they been undertaken at a time when the public mind was unexcited, might have been pursued with advantage to all concerned. But they were established merely with a view of raising the shares in the market. The projectors took the first opportunity of a rise to sell out, and next morning the scheme was at an end. Maitland, in his History of London, gravely informs us that one of the projects which received great encouragement was for the establishment of a company “to make deal boards out of sawdust.” This is, no doubt, intended as a joke; but there is abundance of evidence to show that dozens of schemes, hardly a whit more reasonable, lived their little day, ruining hundreds ere they fell. One of them was for a wheel for perpetual motion – capital one million; another was “for encouraging the breed of horses in England, and improving of glebe and church lands, and repairing and rebuilding parsonage and vicarage houses.” Why the clergy, who were so mainly interested in the latter clause, should have taken so much interest in the first, is only to be explained on the supposition that the scheme was projected by a knot of the fox-hunting parsons, once so common in England. The shares of this company were rapidly subscribed for.

But the most absurd and preposterous of all, and which showed, more completely than any other, the utter madness of the people, was one started by an unknown adventurer, entitled “A Company for carrying on an Undertaking of Great Advantage, but Nobody to know What It Is.” Were not the facts stated by scores of credible witnesses, it would be impossible to believe that any person could have been duped by such a project. The man of genius who essayed this bold and successful inroad upon public credulity merely stated in his prospectus that the required capital was half a million, in five thousand shares of one hundred pounds each, deposit two pounds per share. Each subscriber paying his deposit would be entitled to one hundred pounds per annum per share. How this immense profit was to be obtained he did not condescend to inform them at that time but promised that in a month full particulars should be duly announced, and a call made for the remaining ninety-eight pounds of the subscription. Next morning, at nine o’clock, this great man opened an office in Cornhill. Crowds of people beset his door, and when he shut up, at three o’clock, he found that no less than one thousand shares had been subscribed for and the deposits paid. He was thus, in five hours, the winner of two thousand pounds. He was philosopher enough to be contented with his venture and set off the same evening for the Continent. He was never heard of again.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.