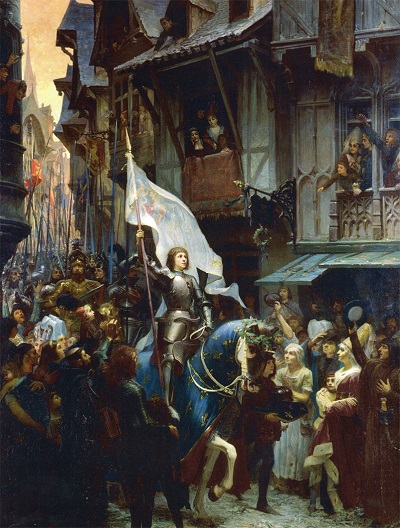

Jeanne appeared at the camp at Blois, clad in a new suit of brilliant white armor, mounted on a stately black war-horse, and with a lance in her right hand, which she had learned to wield with skill and grace.

Continuing Joan of Arc at Orleans,

our selection from Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World by Sir Edward S. Creasy published in 1851. The selection is presented in six easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Joan of Arc at Orleans.

Time: 1429

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

His features may probably have been seen by her previously in portraits or have been described to her by others; but she herself believed that her “voices” inspired her when she addressed the King, and the report soon spread abroad that the holy Maid had found the King by a miracle; and this, with many other similar rumors, augmented the renown and influence that she now rapidly acquired.

The state of public feeling in France was now favorable to an enthusiastic belief in a divine interposition in favor of the party that had hitherto been unsuccessful and oppressed. The humiliations which had befallen the French royal family and nobility were looked on as the just judgments of God upon them for their vice and impiety. The misfortunes that had come upon France as a nation were believed to have been drawn down by national sins. The English, who had been the instruments of heaven’s wrath against France, seemed now, by their pride and cruelty, to be fitting objects of it themselves.

France in that age was a profoundly religious country. There was ignorance, there was superstition, there was bigotry; but there was faith — a faith that itself worked true miracles, even while it believed in unreal ones. At this time, also, one of those devotional movements began among the clergy in France, which from time to time occur in national churches, without it being possible for the historian to assign any adequate human cause for their immediate date or extension. Numberless friars and priests traversed the rural districts and towns of France, preaching to the people that they must seek from heaven a deliverance from the pillages of the soldiery and the insolence of the foreign oppressors.

The idea of a providence that works only by general laws was wholly alien to the feelings of the age. Every political event, as well as every natural phenomenon, was believed to be the immediate result of a special mandate of God. This led to the belief that his holy angels and saints were constantly employed in executing his commands and mingling in the affairs of men. The Church encouraged these feelings, and at the same time sanctioned the concurrent popular belief that hosts of evil spirits were also ever actively interposing in the current of earthly events, with whom sorcerers and wizards could league themselves, and thereby obtain the exercise of supernatural power.

Thus all things favored the influence which Jeanne obtained both over friends and foes. The French nation, as well as the English and the Burgundians, readily admitted that superhuman beings inspired her; the only question was whether these beings were good or evil angels; whether she brought with her “airs from heaven or blasts from hell.” This question seemed to her countrymen to be decisively settled in her favor by the austere sanctity of her life, by the holiness of her conversation, but still more by her exemplary attention to all the services and rites of the Church. The Dauphin at first feared the injury that might be done to his cause if he laid himself open to the charge of having leagued himself with a sorceress. Every imaginable test, therefore, was resorted to in order to set Jeanne’s orthodoxy and purity beyond suspicion. At last Charles and his advisers felt safe in accepting her services as those of a true and virtuous Christian daughter of the holy Church.

It is, indeed, probable that Charles himself and some of his counsellors may have suspected Jeanne of being a mere enthusiast, and it is certain that Dunois and others of the best generals took considerable latitude in obeying or deviating from the military orders that she gave. But over the mass of the people and the soldiery her influence was unbounded. While Charles and his doctors of theology, and court ladies, had been deliberating as to recognizing or dismissing the Maid, a considerable period had passed away during which a small army, the last gleanings, as it seemed, of the English sword, had been assembled at Blois, under Dunois, La Hire, Xaintrailles, and other chiefs, who to their natural valor were now beginning to unite the wisdom that is taught by misfortune. It was resolved to send Jeanne with this force and a convoy of provisions to Orleans. The distress of that city had now become urgent. But the communication with the open country was not entirely cut off: the Orleannais had heard of the holy Maid whom Providence had raised up for their deliverance, and their messengers earnestly implored the Dauphin to send her to them without delay.

Jeanne appeared at the camp at Blois, clad in a new suit of brilliant white armor, mounted on a stately black war-horse, and with a lance in her right hand, which she had learned to wield with skill and grace. Her head was unhelmeted, so that all could behold her fair and expressive features, her deep-set and earnest eyes, and her long black hair, which was parted across her forehead, and bound by a ribbon behind her back. She wore at her side a small battle-axe, and the consecrated sword, marked on the blade with five crosses, which had at her bidding been taken for her from the shrine of St. Catharine at Fierbois. A page carried her banner, which she had caused to be made and embroidered as her voices enjoined. It was white satin, strewn with fleurs-de-lis, and on it were the words

JHESUS MARIA,”

and the representation of the Savior in his glory. Jeanne afterward generally bore her banner herself in battle; she said that though she loved her sword much, she loved her banner forty times as much and she loved to carry it, because it could not kill anyone.

Thus accoutred, she came to lead the troops of France, who looked with soldierly admiration on her well-proportioned and upright figure, the skill with which she managed her war-horse, and the easy grace with which she handled her weapons. Her military education had been short, but she had availed herself of it well. She had also the good sense to interfere little with the maneuvers of the troops, leaving these things to Dunois and others whom she had the discernment to recognize as the best officers in the camp.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.