Today’s installment concludes Joan of Arc at Orleans,

our selection from Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World by Sir Edward S. Creasy published in 1851.

If you have journeyed through the installments of this series so far, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of six thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Joan of Arc at Orleans.

Time: 1429

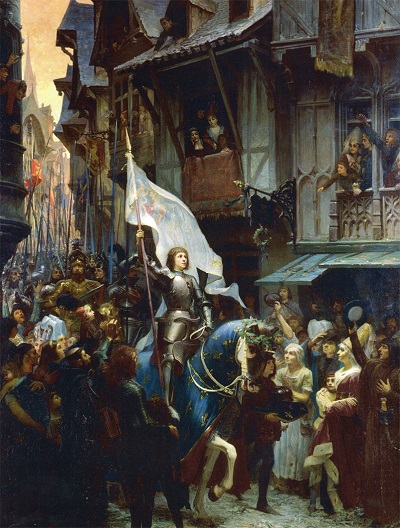

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Gladsdale resolved to withdraw his men from the landward bulwark and concentrate his whole force in the Tourelles themselves. He was passing for this purpose across the drawbridge that connected the Tourelles and the tête-du-pont, when Jeanne, who by this time had scaled the wall of the bulwark, called out to him, “Surrender! surrender to the King of Heaven! Ah, Glacidas, you have foully wronged me with your words, but I have great pity on your soul and the souls of your men.” The Englishman, disdainful of her summons, was striding on across the drawbridge, when a cannon-shot from the town carried it away, and Gladsdale perished in the water that ran beneath. After his fall, the remnant of the English abandoned all further resistance. Three hundred of them had been killed in the battle and two hundred were made prisoners.

The broken arch was speedily repaired by the exulting Orleannais, and Jeanne made her triumphal reentry into the city by the bridge that had so long been closed. Every church in Orleans rang out its gratulating peal; and throughout the night the sounds of rejoicing echoed, and the bonfires blazed up from the city. But in the lines and forts which the besiegers yet retained on the northern shore, there was anxious watching of the generals, and there was desponding gloom among the soldiery. Even Talbot now counselled retreat. On the following morning the Orleannais, from their walls, saw the great forts called “London” and “St. Lawrence” in flames, and witnessed their invaders busy in destroying the stores and munitions which had been relied on for the destruction of Orleans.

Slowly and sullenly the English army retired; and not before it had drawn up in battle array opposite to the city, as if to challenge the garrison to an encounter. The French troops were eager to go out and attack, but Jeanne forbade it. The day was Sunday.

“In the name of God,” she said, “let them depart, and let us return thanks to God.”

She led the soldiers and citizens forth from Orleans, but not for the shedding of blood. They passed in solemn procession round the city walls, and then, while their retiring enemies were yet in sight, they knelt in thanksgiving to God for the deliverance which he had vouchsafed them.

Within three months from the time of her first interview with the Dauphin, Jeanne had fulfilled the first part of her promise, the raising of the siege of Orleans. Within three months more she had fulfilled the second part also and had stood with her banner in her hand by the high altar at Rheims, while he was anointed and crowned as king Charles VII of France. In the interval she had taken Jargeau, Troyes, and other strong places, and she had defeated an English army in a fair field at Patay. The enthusiasm of her countrymen knew no bounds; but the importance of her services, and especially of her primary achievement at Orleans, may perhaps be best proved by the testimony of her enemies. There is extant a fragment of a letter from the regent Bedford to his royal nephew, Henry VI, in which he bewails the turn that the war has taken, and especially attributes it to the raising of the siege of Orleans by Jeanne. Bedford’s own words, which are preserved in Rymer, are as follows:

And alle thing there prospered for you til the tyme of the Siege of Orleans taken in hand God knoweth by what advis. At the whiche tyme, after the adventure fallen to the persone of my cousin of Salisbury, whom God assoille, there felle, by the hand of God as it seemeth, a great strook upon your peuple that was assembled there in grete nombre, caused in grete partie, as y trowe, of lakke of sadde beleve, and of unlevefulle doubte, that thei hadde of a disciple and lyme of the Feende, called the Pucelle, that used fals enchantments and sorcerie.

The whiche strooke and discomfiture nott oonly lessed in grete partie the nombre of your peuple there, but as well withdrewe the courage of the remenant in merveillous wyse, and couraiged your adverse partie and ennemys to assemble them forthwith in grete nombre.”

When Charles had been anointed king of France, Jeanne believed that her mission was accomplished. And in truth the deliverance of France from the English, though not completed for many years afterward, was then insured. The ceremony of a royal coronation and anointment was not in those days regarded as a mere costly formality. It was believed to confer the sanction and the grace of heaven upon the prince, who had previously ruled with mere human authority. Thenceforth he was the Lord’s Anointed. Moreover, one of the difficulties that had previously lain in the way of many Frenchmen when called on to support Charles VII was now removed. He had been publicly stigmatized, even by his own parents, as no true son of the royal race of France. The queen-mother, the English, and the partisans of Burgundy called him the “Pretender to the title of Dauphin”; but those who had been led to doubt his legitimacy were cured of their skepticism by the victories of the holy Maid and by the fulfilment of her pledges. They thought that heaven had now declared itself in favor of Charles as the true heir of the crown of St. Louis, and the tales about his being spurious were thenceforth regarded as mere English calumnies.

With this strong tide of national feeling in his favor, with victorious generals and soldiers round him, and a dispirited and divided enemy before him, he could not fail to conquer, though his own imprudence and misconduct, and the stubborn valor which the English still from time to time displayed, prolonged the war in France until the civil Wars of the Roses broke out in England, and left France to peace and repose.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Joan of Arc at Orleans by Sir Edward S. Creasy from his book Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World published in 1851. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Joan of Arc at Orleans here and here and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.