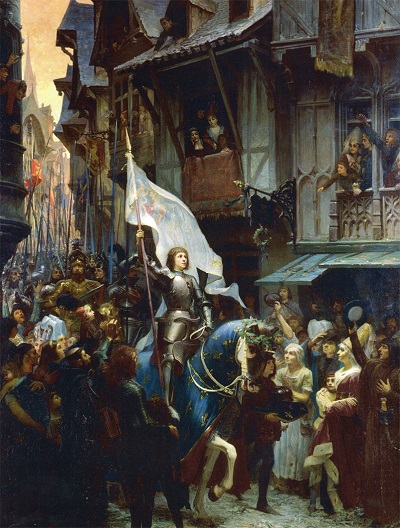

The whole population thronged around her; and men, women, and children strove to touch her garments or her banner or her charger.

Continuing Joan of Arc at Orleans,

our selection from Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World by Sir Edward S. Creasy published in 1851. The selection is presented in six easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Joan of Arc at Orleans.

Time: 1429

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Her tactics in action were simple enough. As she herself described it, “I used to say to them, ‘Go boldly in among the English,’ and then I used to go boldly in myself.” Such, as she told her inquisitors, was the only spell she used, and it was one of power. But, while interfering little with the military discipline of the troops, in all matters of moral discipline she was inflexibly strict. All the abandoned followers of the camp were driven away. She compelled both generals and soldiers to attend regularly at confessional. Her chaplain and other priests marched with the army under her orders; and at every halt, an altar was set up and the sacrament administered. No oath or foul language passed without punishment or censure. Even the roughest and most hardened veterans obeyed her. They had put off for a time the bestial coarseness which had grown on them during a life of bloodshed and rapine; they felt that they must go forth in a new spirit to a new career and acknowledged the beauty of the holiness in which the heaven-sent Maid was leading them to certain victory.

Jeanne marched from Blois on the 25th of April with a convoy of provisions for Orleans, accompanied by Dunois, La Hire, and the other chief captains of the French, and on the evening of the 28th they approached the town. In the words of the old chronicler Hall:

The Englishmen, perceiving that thei within could not long continue for faute of vitaile and pouder, kepte not their watche so diligently as thei were accustomed, nor scoured now the countrey environed as thei before had ordained. Whiche negligence the citizens shut in perceiving, sent worde thereof to the French captaines, which, with Pucelle, in the dedde tyme of the nighte, and in a greate rayne and thundere, with all their vitaile and artillery, entered into the citie.”

When it was day, the Maid rode in solemn procession through the city, clad in complete armor, and mounted on a white horse. Dunois was by her side, and all the bravest knights of her army and of the garrison followed in her train. The whole population thronged around her; and men, women, and children strove to touch her garments or her banner or her charger. They poured forth blessings on her, whom they already considered their deliverer. In the words used by two of them afterward before the tribunal which reversed the sentence but could not restore the life of the virgin-martyr of France, “the people of Orleans, when they first saw her in their city, thought that it was an angel from heaven that had come down to save them.”

Jeanne spoke gently in reply to their acclamations and addresses. She told them to fear God, and trust in him for safety from the fury of their enemies. She first went to the principal church, where Te Deum was chanted; and then she took up her abode at the house of Jacques Bourgier, one of the principal citizens, and whose wife was a matron of good repute. She refused to attend a splendid banquet which had been provided for her and passed nearly all her time in prayer.

When it was known by the English that the Maid was in Orleans, their minds were not less occupied about her than were the minds of those in the city; but it was in a very different spirit. The English believed in her supernatural mission as firmly as the French did, but they thought her a sorceress who had come to overthrow them by her enchantments. An old prophecy, which told that a damsel from Lorraine was to save France, had long been current, and it was known and applied to Jeanne by foreigners as well as by the natives. For months the English had heard of the coming Maid, and the tales of miracles which she was said to have wrought had been listened to by the rough yeomen of the English camp with anxious curiosity and secret awe. She had sent a herald to the English generals before she marched for Orleans, and he had summoned the English generals in the name of the most High to give up to the Maid, who was sent by heaven, the keys of the French cities which they had wrongfully taken; and he also solemnly adjured the English troops, whether archers or men of the companies of war or gentlemen or others, who were before the city of Orleans, to depart thence to their homes, under peril of being visited by the judgment of God.

On her arrival in Orleans, Jeanne sent another similar message; but the English scoffed at her from their towers and threatened to burn her heralds. She determined, before she shed the blood of the besiegers, to repeat the warning with her own voice and accordingly, she mounted one of the boulevards of the town, which was within hearing of the Tourelles, and thence she spoke to the English, and bade them depart, otherwise they would meet with shame and woe.

Sir William Gladsdale — whom the French call “Glacidas” — commanded the English post at the Tourelles, and he and another English officer replied by bidding her go home and keep her cows, and by ribald jests that brought tears of shame and indignation into her eyes. But, though the English leaders vaunted aloud, the effect produced on their army by Jeanne’s presence in Orleans was proved four days after her arrival, when, on the approach of reinforcements and stores to the town, Jeanne and La Hire marched out to meet them, and escorted the long train of provision wagons safely into Orleans, between the bastiles of the English, who cowered behind their walls instead of charging fiercely and fearlessly, as had been their wont, on any French band that dared to show itself within reach.

Thus far she had prevailed without striking a blow; but the time was now come to test her courage amid the horrors of actual slaughter. On the afternoon of the day on which she had escorted the reinforcements into the city, while she was resting fatigued at home, Dunois had seized an advantageous opportunity of attacking the English bastile of St. Loup, and a fierce assault of the Orleannais had been made on it, which the English garrison of the fort stubbornly resisted. Jeanne was roused by a sound which she believed to be that of her heavenly voices; she called for her arms and horse, and, quickly equipping herself, she mounted to ride off to where the fight was raging. In her haste she had forgotten her banner; she rode back, and, without dismounting, had it given to her from the window, and then she galloped to the gate whence the sally had been made.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.