An English archer sent an arrow at her, which pierced her corselet and wounded her severely between the neck and shoulder.

Continuing Joan of Arc at Orleans,

our selection from Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World by Sir Edward S. Creasy published in 1851. The selection is presented in six easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Joan of Arc at Orleans.

Time: 1429

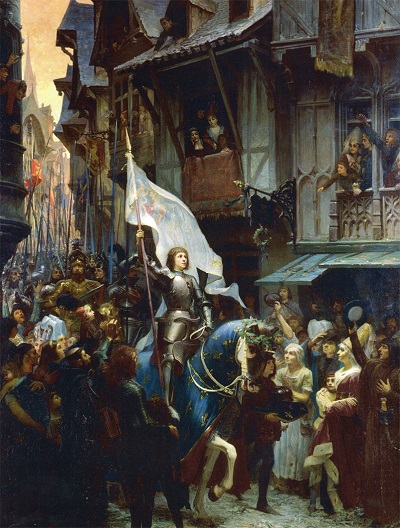

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

On her way she met some of the wounded French who had been carried back from the fight. “Ha!” she exclaimed, “I never can see French blood flow without my hair standing on end.” She rode out of the gate, and met the tide of her countrymen, who had been repulsed from the English fort, and were flying back to Orleans in confusion. At the sight of the holy Maid and her banner they rallied and renewed the assault, Jeanne rode forward at their head, waving her banner and cheering them on. The English quailed at what they believed to be the charge of hell; St. Loup was stormed, and its defenders put to the sword, except some few, whom Jeanne succeeded in saving. All her woman’s gentleness returned when the combat was over. It was the first time that she had ever seen a battlefield. She wept at the sight of so many bleeding corpses; and her tears flowed doubly when she reflected that they were the bodies of Christian men who had died without confession.

The next day was Ascension Day, and it was passed by Jeanne in prayer. But on the following morrow it was resolved by the chiefs of the garrison to attack the English forts on the south of the river. For this purpose, they crossed the river in boats, and after some severe fighting, in which the Maid was wounded in the heel, both the English bastiles of the Augustins and St. Jean de Blanc were captured. The Tourelles were now the only posts which the besiegers held on the south of the river. But that post was formidably strong, and by its command of the bridge it was the key to the deliverance of Orleans. It was known that a fresh English army was approaching under Fastolfe to reinforce the besiegers and, should that army arrive while the Tourelles were yet in the possession of their comrades, there was great peril of all the advantages which the French had gained being nullified, and of the siege being again actively carried on.

It was resolved, therefore, by the French to assail the Tourelles at once, while the enthusiasm which the presence and the heroic valor of the Maid had created was at its height. But the enterprise was difficult. The rampart of the tête-du-pont, or landward bulwark, of the Tourelles was steep and high, and Sir John Gladsdale occupied this all-important fort with five hundred archers and men-at-arms, who were the very flower of the English army.

Early in the morning of the 7th of May some thousands of the best French troops in Orleans heard mass and attended the confessional by Jeanne’s orders, and then crossing the river in boats, as on the preceding day, they assailed the bulwark of the Tourelles “with light hearts and heavy hands.” But Gladsdale’s men, encouraged by their bold and skillful leader, made a resolute and able defense. The Maid planted her banner on the edge of the fosse, and then, springing down into the ditch, she placed the first ladder against the wall and began to mount. An English archer sent an arrow at her, which pierced her corselet and wounded her severely between the neck and shoulder. She fell bleeding from the ladder; and the English were leaping down from the wall to capture her, but her followers bore her off. She was carried to the rear and laid upon the grass; her armor was taken off, and the anguish of her wound and the sight of her blood made her at first tremble and weep.

But her confidence in her celestial mission soon returned: her patron saints seemed to stand before her and reassure her. She sat up and drew the arrow out with her own hands. Some of the soldiers who stood by wished to stanch the blood by saying a charm over the wound; but she forbade them, saying that she did not wish to be cured by unhallowed means. She had the wound dressed with a little oil, and then, bidding her confessor come to her, she betook herself to prayer.

In the meanwhile, the English in the bulwark of the Tourelles had repulsed the oft-renewed efforts of the French to scale the wall. Dunois, who commanded the assailants, was at last discouraged, and gave orders for a retreat to be sounded. Jeanne sent for him and the other generals and implored them not to despair.

“By my God,” she said to them, “you shall soon enter in there. Do not doubt it. When you see my banner wave again up to the wall, to your arms again! the fort is yours. For the present, rest a little and take some food and drink.”

“They did so,” says the old chronicler of the siege, “for they obeyed her marvelously.”

The faintness caused by her wound had now passed off, and she headed the French in another rush against the bulwark. The English, who had thought her slain, were alarmed at her reappearance, while the French pressed furiously and fanatically forward. A Biscayan soldier was carrying Jeanne’s banner. She had told the troops that directly the banner touched the wall they should enter. The Biscayan waved the banner forward from the edge of the fosse, and touched the wall with it, and then all the French host swarmed madly up the ladders that now were raised in all directions against the English fort. At this crisis the efforts of the English garrison were distracted by an attack from another quarter. The French troops who had been left in Orleans had placed some planks over the broken arch of the bridge, and advanced across them to the assault of the Tourelles on the northern side.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.