This series has six easy 5-minute installments. This first installment: Orleans Seems Doomed.

Introduction

In 1415 the Battle of Agincourt put England on the road to victory at last in the Hundred Years (!) War. A few years later the English began the siege of the key stronghold of Orleans.

France now realized that her condition was wellnigh hopeless. The chivalry of France had been wasted in terrible wars. The spirits of her soldiers were sunk by repeated disaster. The greater part of her territory was in enemy hands. The condition of the peasantry in the countryside was too wretched to be described. Anarchy and brigandage were everywhere. Looking to the native French court, the king seemed inadequate.

Saving France would take a miracle. She was on the way.

This selection is from Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World by Sir Edward S. Creasy published in 1851. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Sir Edward S. Creasy (1812-1878) was an English historian. His Fifteen Battles book was his magnum opus.

Time: 1429

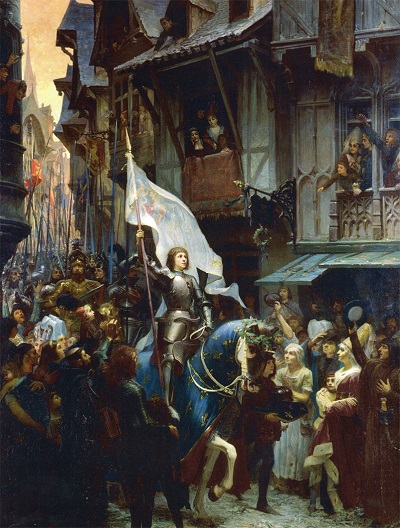

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Orleans was looked upon as the last stronghold of the French national party. If the English could once obtain possession of it, their victorious progress through the residue of the kingdom seemed free from any serious obstacle. Accordingly, the Earl of Salisbury, one of the bravest and most experienced of the English generals, who had been trained under Henry V, marched to the attack of the all-important city and, after reducing several places of inferior consequence in the neighborhood, appeared with his army before its walls on the 12th of October, 1428.

The city of Orleans itself was on the north side of the Loire, but its suburbs extended far on the southern side, and a strong bridge connected them with the town. A fortification, which in modern military phrase would be termed a tête-du-pont, defended the bridge head on the southern side, and two towers, called the Tourelles, were built on the bridge itself, at a little distance from the tête-du-pont. Indeed, the solid masonry of the bridge terminated at the Tourelles; and the communication thence with the tête-du-pont and the southern shore was by means of a drawbridge. The Tourelles and the tête-du-pont formed together a strong-fortified post, capable of containing a garrison of considerable strength; and so long as this was in possession of the Orleannais, they could communicate freely with the southern provinces, the inhabitants of which, like the Orleannais themselves, supported the cause of their dauphin against the foreigners.

Lord Salisbury rightly judged the capture of the Tourelles to be the most material step toward the reduction of the city itself. Accordingly, he directed his principal operations against this post, and after some severe repulses he carried the Tourelles by storm on the 23rd of October. The French, however, broke down the arches of the bridge that were nearest to the north bank, and thus rendered a direct assault from the Tourelles upon the city impossible. But the possession of this post enabled the English to distress the town greatly by a battery of cannon which they planted there, and which commanded some of the principal streets.

It has been observed by Hume that this is the first siege in which any important use appears to have been made of artillery. And even at Orleans both besiegers and besieged seem to have employed their cannons merely as instruments of destruction against their enemy’s men, and not to have trusted to them as engines of demolition against their enemy’s walls and works. The efficacy of cannon in breaching solid masonry was taught Europe by the Turks a few years afterward, at the memorable siege of Constantinople.

In our French wars, as in the wars of the classic nations, famine was looked on as the surest weapon to compel the submission of a well-walled town; and the great object of the besiegers was to effect a complete circumvallation. The great ambit of the walls of Orleans, and the facilities which the river gave for obtaining succors and supplies, rendered the capture of the town by this process a matter of great difficulty. Nevertheless, Lord Salisbury, and Lord Suffolk, who succeeded him in command of the English after his death by a cannon-ball, carried on the necessary works with great skill and resolution. Six strongly-fortified posts, called bastilles, were formed at certain intervals round the town, and the purpose of the English engineers was to draw strong lines between them. During the winter, little progress was made with the intrenchments, but when the spring of 1429 came, the English resumed their work with activity; the communications between the city and the country became more difficult, and the approach of want began already to be felt in Orleans.

The besieging force also fared hardly for stores and provisions, until relieved by the effects of a brilliant victory which Sir John Fastolf, one of the best English generals, gained at Rouvrai, near Orleans, a few days after Ash Wednesday, 1429. With only sixteen hundred fighting men, Sir John completely defeated an army of French and Scots, four thousand strong, which had been collected for the purpose of aiding the Orleannais and harassing the besiegers. After this encounter, which seemed decisively to confirm the superiority of the English in battle over their adversaries, Fastolf escorted large supplies of stores and food to Suffolk’s camp, and the spirits of the English rose to the highest pitch at the prospect of the speedy capture of the city before them, and the consequent subjection of all France beneath their arms.

The Orleannais now, in their distress, offered to surrender the city into the hands of the Duke of Burgundy, who, though the ally of the English, was yet one of their native princes. The regent Bedford refused these terms, and the speedy submission of the city to the English seemed inevitable. The dauphin Charles, who was now at Chinon with his remnant of a court, despaired of continuing any longer the struggle for his crown, and was only prevented from abandoning the country by the more masculine spirits of his mistress and his Queen. Yet neither they nor the boldest of Charles’ captains could have shown him where to find resources for prolonging war; and least of all could any human skill have predicted the quarter whence rescue was to come to Orleans and to France.

In the village of Domremy, on the borders of Lorraine, there was a poor peasant of the name of Jacques d’Arc, respected in his station of life, and who had reared a family in virtuous habits and in the practice of the strictest devotion. His eldest daughter was named by her parents Jeannette, but she was called Jeanne by the French, which was Latinized into Johanna, and Anglicized into Joan.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.