Serious questions affecting the working of our party system have arisen from unfortunate differences between the two Houses. My Ministers have this important subject under consideration with a view to the solution of the difficulty.”

Continuing English House of Lords Falls,

with a selection from special article in Great Events by Famous Historians, Vol. 21 by Arthur Ponsonby published in 1914. This selection is presented in 5 easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in English House of Lords Falls.

Time: 1911

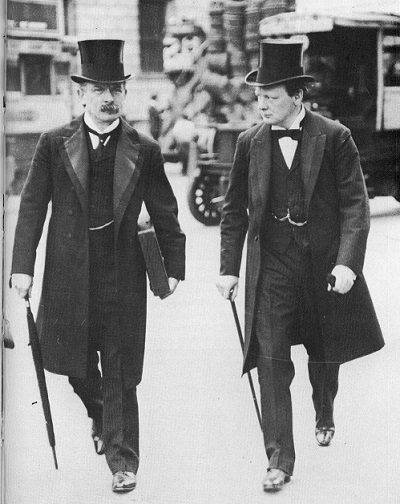

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

But for the next ten years (1895-1905) the Conservatives were in office, and again it was impossible to bring the matter to a head, though the past was not forgotten. When the Liberals were returned in 1906 with their colossal majority, every Liberal was well aware that before long the same trouble would inevitably arise, and that a settlement of the question could not be long delayed. The record of the House of Lords’ activities during the last five years has been so indelibly impressed on the public mind that only a very brief recapitulation of events is necessary.

At the outset their action was tentative. This was shown by the conferences and negotiations to arrive at a settlement on the Education Bill, which was the first Liberal measure in 1906. But these broke down, and defiance was found to be completely successful. Mr. Balfour, the leader of the Conservative party, realized that although he was in a small minority in the House of Commons, yet he could still control legislation, and when he saw how effectively the destructive weapon of the veto could be used, he became bolder, and, as with all vicious habits, increased indulgence encouraged appetite. Had Mr. Balfour played his trump-card — the Lords’ veto — with greater foresight and restraint, it may safely be said that the House of Lords might have continued for another generation, or, at any rate, for another decade, with its authority unimpaired, though sooner or later it was bound to abuse its power; but the temptation was too great, and Mr. Balfour became reckless.

The three crucial mistakes on the part of the Opposition from the point of view of pure tactics were: First, the destruction of the Education Bill of 1906. In view of the historic attitude of the Lords to all questions of religious freedom and general enlightenment, it was not surprising that they should stand in the way of a greater equality of opportunity for all denominations in matters of education. Six times between 1838 and 1857 they rejected Bills for removing Jewish disabilities; three times between 1858 and 1869 they vetoed the abolition of Church Rates. For thirty-six years (1835-1871) the admission of Nonconformists to the universities by the abolition of tests was delayed by them. It was only to be expected, therefore, that they would be deaf to the popular outcry that had been caused by the Balfour Education Bill of 1902. But in the very first session of the Parliament in which the Government had been returned to power by the immense majority of 354, that they should immediately show their teeth and claws was, from their own point of view, as events proved, a vital error. Their second mistake was the rejection in 1908 by a body of Peers at Lansdowne House of the Licensing Bill, which had occupied many weeks of the time of the House of Commons. This was rightly regarded as a gratuitous insult to the House of elected representatives. Finally, their culminating act of folly was the rejection of the Budget in 1909. It was an outrageous breach of acknowledged constitutional practice, which alienated from them a large body of moderate opinion. In addition to these three notable measures there were, of course, a number of other Bills on land, electoral, and social reform that were either mutilated or thrown out during this period. How could any politician in his senses suppose that a party who possessed any degree of confidence in the country would tamely submit to treatment such as this? While the Lords proceeded light-heartedly with their wrecking tactics, the Liberal Government slowly and cautiously, but with great deliberation, took action step by step. A provocative move on the part of the Lords was met each time by a countermove, and thus gradually the final and decisive phase of the dispute was reached.

After the loss of the Education Bill of 1906, the first note of warning was sounded by Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman. “The resources of the House of Commons,” he declared, “are not exhausted, and I say with conviction that a way must be found, and a way will be found, by which the will of the people expressed through their elected representatives in this House will be made to prevail.”

The first mention of the subject in a King’s Speech occurred in March, 1907, when this significant phrase was used: “Serious questions affecting the working of our party system have arisen from unfortunate differences between the two Houses. My Ministers have this important subject under consideration with a view to the solution of the difficulty.”

On June 24, 1907, the matter was first definitely brought before the House. Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman moved that “in order to give effect to the will of the people as expressed by their elected representatives, it is necessary that the power of the other House to alter or reject Bills passed by this House should be so restricted by law as to secure that within the limits of a single Parliament the final decision of the Commons shall prevail.” To the evident surprise of the Opposition he sketched a definite plan for curtailing the veto of the House of Lords. This was followed in July by the introduction of resolutions laying down in full detail the exact procedure. In his statement Sir Henry made it very clear that the issue was confined to the relations between the two Houses: — “Let me point out that the plan which I have sketched to the House does not in the least preclude or prejudice any proposals which may be made for the reform of the House of Lords. The constitution and composition of the House of Lords is a question entirely independent of my subject. My resolution has nothing to do with the relations of the two Houses to the Crown, but only with the relations of the two Houses to each other.”

In 1908, Mr. Asquith became Prime Minister, but no further action was taken. On the rejection of the Licensing Bill, however, he showed that the Government were fully aware of the extreme gravity of the question but intended to choose their own time to deal with it. Speaking at the National Liberal Club in December, he said: “The question I want to put to you and to my fellow Liberals outside is this: Is this state of things to continue? We say that it must be brought to an end, and I invite the Liberal party to-night to treat the veto of the House of Lords as the dominating issue in politics — the dominant issue, because in the long run it overshadows and absorbs every other.” When pressed on the Address at the beginning of the following session by his supporters, who were impatient for action, he explained the position of the Government: “I repeat we have no intention to shirk or postpone the issue we have raised…. I can give complete assurance that at the earliest possible moment consistent with the discharge by this Parliament of the obligations I have indicated, the issue will be presented and submitted to the country.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Arthur Ponsonby begins here. Sydney Brooks begins here. Captain George Swinton begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.