Today’s installment concludes Canute Becomes King of England,

our selection from History of England by David Hume published in 1754.

If you have journeyed through the installments of this series so far, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of four thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Canute Becomes King of England.

Time: 1017

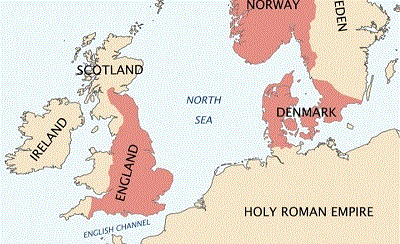

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

Canute, having settled his power in England beyond all danger of a revolution, made a voyage to Denmark, in order to resist the attacks of the King of Sweden; and he carried along with him a great body of the English, under the command of Earl Godwin. This nobleman had here an opportunity of performing a service, by which he both reconciled the King’s mind to the English nation and, gaining to himself the friendship of his sovereign, laid the foundation of that immense fortune which he acquired to his family. He was stationed next to the Swedish camp, and observing a favorable opportunity, which he was obliged suddenly to seize, he attacked the enemy in the night, drove them from their trenches, threw them into disorder, pursued his advantage, and obtained a decisive victory over them. Next morning Canute, seeing the English camp entirely abandoned, imagined that those disaffected troops had deserted to the enemy: he was agreeably surprised to find that they were at that time engaged in pursuit of the discomfited Swedes. He was so pleased with this success, and with the manner of obtaining it, that he bestowed his daughter in marriage upon Godwin, and treated him ever after with entire confidence and regard.

In another voyage, which he made afterward to Denmark, Canute attacked Norway, and, expelling the just but unwarlike Olaus, kept possession of his kingdom till the death of that prince. He had now by his conquests and valor attained the utmost height of grandeur: having leisure from wars and intrigues, he felt the unsatisfactory nature of all human enjoyments; and equally weary of the glories and turmoils of this life, he began to cast his view toward that future existence, which it is so natural for the human mind, whether satiated by prosperity or disgusted with adversity, to make the object of its attention. Unfortunately, the spirit which prevailed in that age gave a wrong direction to his devotion: instead of making compensation to those whom he had injured by his former acts of violence, he employed himself entirely in those exercises of piety which the monks represented as the most meritorious. He built churches, he endowed monasteries, he enriched the ecclesiastics, and he bestowed revenues for the support of chantries at Assington and other places, where he appointed prayers to be said for the souls of those who had there fallen in battle against him. He even undertook a pilgrimage to Rome, where he resided a considerable time: besides obtaining from the pope some privileges for the English school erected there, he engaged all the princes through whose dominions he was obliged to pass to desist from those heavy impositions and tolls which they were accustomed to exact from the English pilgrims. By this spirit of devotion, no less than by his equitable and politic administration, he gained, in a good measure, the affections of his subjects.

Canute, the greatest and most powerful monarch of his time, sovereign of Denmark and Norway, as well as of England, could not fail of meeting with adulation from his courtiers; a tribute which is liberally paid even to the meanest and weakest princes. Some of his flatterers, breaking out one day in admiration of his grandeur, exclaimed that everything was possible for him; upon which the monarch, it is said, ordered his chair to be set on the seashore while the tide was rising; and as the waters approached, he commanded them to retire, and to obey the voice of him who was lord of the ocean. He feigned to sit some time in expectation of their submission but when the sea still advanced toward him, and began to wash him with its billows, he turned to his courtiers, and remarked to them that every creature in the universe was feeble and impotent, and that power resided with one Being alone, in whose hands were all the elements of nature; who could say to the ocean, “Thus far shalt thou go, and no farther,” and who could level with his nod the most towering piles of human pride and ambition.

The only memorable action which Canute performed after his return from Rome was an expedition against Malcolm, King of Scotland. During the reign of Ethelred, a tax of a shilling a hide had been imposed on all the lands of England. It was commonly called danegelt; because the revenue had been employed either in buying peace with the Danes or in making preparations against the inroads of that hostile nation. That monarch had required that the same tax should be paid by Cumberland, which was held by the Scots; but Malcolm, a warlike prince, told him that as he was always able to repulse the Danes by his own power, he would neither submit to buy peace of his enemies nor pay others for resisting them. Ethelred, offended at this reply, which contained a secret reproach on his own conduct, undertook an expedition against Cumberland; but though he committed ravages upon the country, he could never bring Malcolm to a temper more humble or submissive. Canute, after his accession, summoned the Scottish King to acknowledge himself a vassal for Cumberland to the Crown of England; but Malcolm refused compliance, on pretense that he owed homage to those princes only who inherited that kingdom by right of blood. Canute was not of a temper to bear this insult; and the King of Scotland soon found that the scepter was in very different hands from those of the feeble and irresolute Ethelred. Upon Canute’s appearing on the frontiers with a formidable army, Malcolm agreed that his grandson and heir, Duncan, whom he put in possession of Cumberland, should make the submissions required, and that the heirs of Scotland should always acknowledge themselves vassals to England for that province.

Canute passed four years in peace after this enterprise, and he died at Shaftesbury; leaving three sons, Sweyn, Harold, and Hardicanute. Sweyn, whom he had by his first marriage with Alfwen, daughter of the Earl of Hampshire, was crowned in Norway; Hardicanute, whom Emma had borne him, was in possession of Denmark; Harold, who was of the same marriage with Sweyn, was at that time in England.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Canute Becomes King of England by David Hume from his book History of England published in 1754. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Canute Becomes King of England here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.