Among the other misfortunes of the English, treachery and disaffection had crept in among the nobility and prelates.

Continuing Canute Becomes King of England,

our selection from History of England by David Hume published in 1754. The selection is presented in four easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Canute Becomes King of England.

Time: 1017

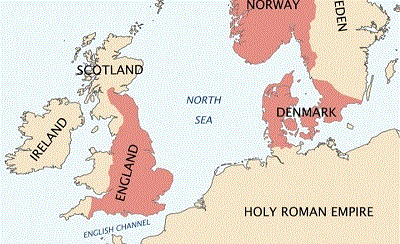

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

This measure did not bring them even that short interval of repose which they had expected from it. The Danes, disregarding all engagements, continued their devastations and hostilities; levied a new contribution of eight thousand pounds upon the county of Kent alone; murdered the Archbishop of Canterbury, who had refused to countenance this exaction; and the English nobility found no other resource than that of submitting everywhere to the Danish monarch, swearing allegiance to him, and delivering him hostages for their fidelity. Ethelred, equally afraid of the violence of the enemy and the treachery of his own subjects, fled into Normandy (1013), whither he had sent before him Queen Emma and her two sons, Alfred and Edward. Richard received his unhappy guests with a generosity that does honor to his memory.

The King had not been above six weeks in Normandy when he heard of the death of Sweyn, who expired at Gainsborough before he had time to establish himself in his new-acquired dominions. The English prelates and nobility, taking advantage of this event, sent over a deputation to Normandy, inviting Ethelred to return to them, expressing a desire of being again governed by their native prince, and intimating their hopes that, being now tutored by experience, he would avoid all those errors which had been attended with such misfortunes to himself and to his people. But the misconduct of Ethelred was incurable; on his resuming the government, he discovered the same incapacity, indolence, cowardice, and credulity which had so often exposed him to the insults of his enemies. His son-in-law Edric, notwithstanding his repeated treasons, retained such influence at court as to instill into the King jealousies of Sigefert and Morcar, two of the chief nobles of Mercia. Edric allured them into his house, where he murdered them; while Ethelred participated in the infamy of the action by confiscating their estates and thrusting into a convent the widow of Sigefert. She was a woman of singular beauty and merit; and in a visit which was paid her, during her confinement, by Prince Edmund, the King’s eldest son, she inspired him with so violent an affection that he released her from the convent, and soon after married her without the consent of his father. Meanwhile the English found in Canute, the son and successor of Sweyn, an enemy no less terrible than the prince from whom death had so lately delivered them. He ravaged the eastern coast with merciless fury, and put ashore all the English hostages at Sandwich, after having cut off their hands and noses. He was obliged, by the necessity of his affairs, to make a voyage to Denmark; but, returning soon after, he continued his depredations along the southern coast. He even broke into the counties of Dorset, Wilts, and Somerset, where an army was assembled against him, under the command of Prince Edmund and Duke Edric. The latter still continued his perfidious machinations, and, after endeavoring in vain to get the prince into his power, he found means to disperse the army, and he then openly deserted to Canute with forty vessels.

Notwithstanding this misfortune Edmund was not disconcerted, but, assembling all the force of England, was in a condition to give battle to the enemy. The King had had such frequent experience of perfidy among his subjects that he had lost all confidence in them: he remained at London, pretending sickness, but really from apprehensions that they intended to buy their peace by delivering him into the hands of his enemies. The army called aloud for their sovereign to march at their head against the Danes; and, on his refusal to take the field, they were so discouraged that those vast preparations became ineffectual for the defense of the kingdom. Edmund, deprived of all regular supplies to maintain his soldiers, was obliged to commit equal ravages with those which were practiced by the Danes. After making some fruitless expeditions into the north, which had submitted entirely to Canute’s power, he retired to London, determined there to maintain to the last extremity the small remains of English liberty. He here found everything in confusion by the death of the King, who expired after an unhappy and inglorious reign of thirty-five years (1016). He left two sons by his first marriage, Edmund, who succeeded him, and Edwy, whom Canute afterward murdered. His two sons by the second marriage, Alfred and Edward, were, immediately upon Ethelred’s death, conveyed into Normandy by Queen Emma.

Edmund, who received the name of “Ironside” from his hardy valor, possessed courage and abilities sufficient to have prevented his country from sinking into those calamities but not to raise it from that abyss of misery into which it had already fallen. Among the other misfortunes of the English, treachery and disaffection had crept in among the nobility and prelates; Edmund found no better expedient for stopping the further progress of these fatal evils than to lead his army instantly into the field, and to employ them against the common enemy. After meeting with some success at Gillingham, he prepared himself to decide, in one general engagement, the fate of his crown; and at Scoerston, in the county of Gloucester, he offered battle to the enemy, who were commanded by Canute and Edric. Fortune, in the beginning of the day, declared for him; but Edric, having cut off the head of one Osmer, whose countenance resembled that of Edmund, fixed it on a spear, carried it through the ranks in triumph, and called aloud to the English that it was time to fly; for, behold! the head of their sovereign. And though Edmund, observing the consternation of the troops, took off his helmet, and showed himself to them, the utmost he could gain by his activity and valor was to leave the victory undecided. Edric now took a surer method to ruin him, by pretending to desert to him; and as Edmund was well acquainted with his power, and probably knew no other of the chief nobility in whom he could repose more confidence, he was obliged, notwithstanding the repeated perfidy of the man, to give him a considerable command in the army. A battle soon after ensued at Assington, in Essex, where Edric, flying in the beginning of the day, occasioned the total defeat of the English, followed by a great slaughter of the nobility. The indefatigable Edmund, however, had still resources. Assembling a new army at Gloucester, he was again in condition to dispute the field, when the Danish and English nobility, equally harassed with those convulsions, obliged their kings to come to a compromise and to divide the kingdom between them by treaty. Canute reserved to himself the northern division, consisting of Mercia, East Anglia, and Northumberland, which he had entirely subdued. The southern parts were left to Edmund. This prince survived the treaty about a month. He was murdered at Oxford by two of his chamberlains, accomplices of Edric, who thereby made way for the succession of Canute the Dane to the crown of England.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.