When told that the people of England were very anxious to abolish the House of Lords, the Duke of Northumberland said that they did not understand the question and did not care two brass farthings about it.

Continuing English House of Lords Falls,

Today is our final installment from Sydney Brooks and then we begin the third part of the series with Captain George Swinton. The selections total nine easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in English House of Lords Falls.

Time: 1911

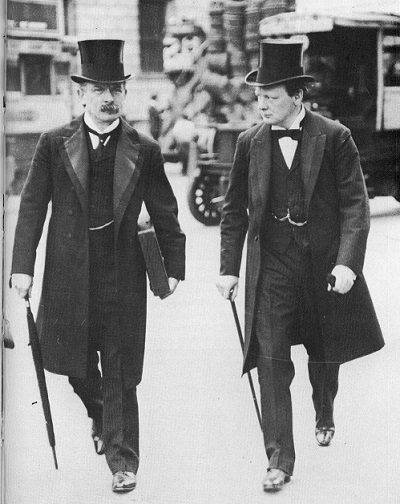

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

Even at the election of December, 1910, when all other issues were admittedly subordinate to the Constitutional issue, it was exceedingly difficult to determine how far the steadfastness of the electorate to the Liberal cause was due to a specific appreciation and approval of the Parliament Bill and of all it involved, and how far it was an expression of general distrust of the Unionists, of irritation with the Lords, and of sympathy with the social and fiscal policies pursued by the Coalition. That the Liberals were justified, by all the rules of the party game, in treating the result of that election as, for all political and Parliamentary purposes, a direct indorsement of their proposals, may be freely granted. It was as near an approach to an ad hoc Referendum as we are ever likely to get under our present system. Party exigencies, or at any rate party tactics, it is true, hurried on the election before the country was prepared for it, before it had recovered from the somnolence induced by the Conference, and before the Opposition had time or opportunity to do more than sketch in their alternative plan. But though the issue was incompletely presented, it was undoubtedly the paramount issue put before the electorate, and the Liberals were fairly entitled to claim that their policy in regard to it had the backing of the majority of the voters of the United Kingdom.

Whether, however, this backing represented a reasoned view of the Constitutional points involved and of the position, prerogatives, and organization of a Second Chamber in the framework of British Government, whether it implied that our people were really interested in and had deeply pondered the relative merits of the Single and Double Chamber systems, is much more doubtful. “When he was told,” said the Duke of Northumberland on August 10th, “that the people of England were very anxious to abolish the House of Lords, his reply was that they did not understand the question and did not care two brass farthings about it.” That perhaps is putting it somewhat too strongly. The country within the last two years has unquestionably felt more vividly than ever before the anomaly of an hereditary Upper Chamber embedded in democratic institutions. It has been stirred by Mr. Lloyd-George’s rhetoric to a mood of vague exasperation with the House of Lords and of ridicule of the order of the Peerage. It has accepted too readily the Liberal version of the central issue as a case of Peers versus People. But while it was satisfied that something ought to be done, I do not believe it realizes precisely what has been accomplished in its name or the consequences that must follow from the passing of the Parliament Bill. There are no signs that it regards the abridgment of the powers of the Upper House as a great democratic victory. There are, on the contrary, manifold signs that it has been bored and bewildered by the whole struggle, and that the extraordinary lassitude with which it watched the debates was a true reflex of its real attitude.

Now we begin the third part of our series with our selection from special article in Great Events by Famous Historians, Vol. 21 by Captain George Swinton, The selection is presented in 2.6 easy 5-minute installments.

Captain George Swinton (1859-1937) was a Scottish army officer and politician.

It has been more like a bullfight than anything else, or perhaps the bullbaiting, almost to the death, which went on in England in days of old. For the Peerage is not quite dead, but sore stricken, robbed of its high functions, propped up and left standing to flatter the fools and the snobs, a kind of painted screen, or a cardboard fortification, armed with cannon which cannot be discharged for fear they bring it down about the defenders’ ears. And in the end, it was all effected so simply, so easily could the bull be induced to charge. A rag was waved, first here, then there, and the dogs barked. That was all.

It is not difficult to be wise after the event. Everybody knows now that with the motley groups of growing strength arrayed against them it behooved the Peers to walk warily, to look askance at the cloaks trailed before them, to realize the danger of accepting challenges, however righteous the cause might be. But no amount of prudence could have postponed the catastrophe for any length of time, for indeed the House of Lords had become an anachronism. Everything had changed since the days when it had its origin, when its members were Peers of the King, not only in name but almost in power, princes of principalities, earls of earldoms, barons of baronies. Then they were in a way enthroned, representing all the people of the territories they dominated, the people they led in war and ruled in peace. They came together as magnates of the land, sitting in an Upper House as Lords of the shire, even as the Knights of the shire sat in the Commons. And this continued long after the feudal system had passed away, carried on not only by the force of tradition, but by a sentiment of respect and real affection; for these feelings were common enough until designing men laid themselves out to destroy them.

Many things combined to make the last phase pass quickly. It was impossible that the Peerage could long survive the Reform Bill, for it took from the great families their pocket boroughs, and so much of their influence. And there followed hard upon it the educational effect of new facilities for exchange of ideas, the railway trains, the penny post, and the halfpenny paper, together with the centralization of general opinion and all government which has resulted therefrom. But above all reasons were the loss of the qualifying ancestral lands, a link with the soil, and the ennobling of landless men. Once divorced from its influence over some countryside a peerage resting on heredity was doomed; for no one can defend a system whereby men of no exceptional ability, representative of nothing, are legislators by inheritance. Should we summon to a conclave of the nations a king who had no kingdom? But the pity of it! Not only the break with eight centuries of history — nay, more, for when had not every king his council of notables? — not only the loss of picturesqueness and sentiment and lofty mien, but the certainty, the appalling certainty, that, when an aristocracy of birth falls, it is not an aristocracy of character or intellect, but an aristocracy — save the mark — of money, which is bound to take its place.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Arthur Ponsonby begins here. Sydney Brooks begins here. Captain George Swinton begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.