Throughout the latter part of the controversy there is little doubt that the Conservatives would have been in a far stronger position had they acted as a united party with a definite policy and a strong leader ready at a moment’s notice to form an alternative Government.

Continuing English House of Lords Falls,

with a selection from special article in Great Events by Famous Historians, Vol. 21 by Arthur Ponsonby published in 1914. This selection is presented in 5 easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in English House of Lords Falls.

Time: 1911

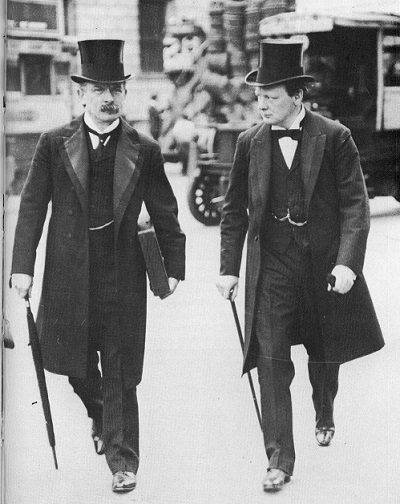

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

The rejection of the Budget in 1909 led to a general election, in which the Government’s method of dealing with the Lords was the main issue. The Liberals were returned again, but when the King’s Speech was read, some confusion was caused by the distinct question of the relations between the two Houses being coupled with a suggested reform of the Second Chamber. This was a departure from the very clear and wise policy of Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, and had it been persisted in it might have broken up the ranks of the Liberal party — very varied and different opinions being held as to the constitution of a Second Chamber. But the stronger course was adopted, and the resolutions subsequently introduced and passed in the House of Commons dealt only with the veto and were to form the preliminary to the introduction of the Bill itself.

Just as matters seemed about to result in a final settlement, King Edward died, and a conference between the leaders of both parties was set up to tide over the awkward interval. The conference was an experiment doomed to failure, as the Liberals had nothing to give away and compromise could only mean a sacrifice of principle. The House met in November to wind up the business, and the Prime Minister announced that an appeal would be made to the country on the single issue of the Lords’ veto, the specific proposals of the Government being placed before the electorate. A Liberal Government was returned to power for the third time in December, 1910, with practically the same majority as in January. The Parliament Bill was introduced and passed in all its stages through the House of Commons with large majorities.

Meanwhile, the Conservatives made no attempt to defend either the action or composition of the House of Lords but adopted an apologetic attitude. They agreed that the Second Chamber must be reformed, and during the second general election in 1910 some of them declared for the Referendum as a solution of the difficulty of deadlocks between the two Houses. But there was an entire absence of sincerity about their proposals, which were not thought out, but obviously only superficial expedients hurriedly grasped at by a party in distress. Their reform scheme, introduced by Lord Lansdowne, was revolutionary, and, at the same time, fanciful and confused. It was ridiculed by their opponents and received with frigid disapproval by their supporters. Still, they acted as if they were confident that in the long run they could ward off the final blow. They were persuaded that the Liberal Government would neither have the courage nor the power to accomplish their purpose. “Why waste time over abstract resolutions?” asked Mr. Balfour. “The Liberal party,” he said, “has a perfect passion for abstract resolutions” — and again, “it is quite obvious they do not mean business.” Even when the Bill itself was introduced, they still did not believe that its passage through the House of Lords could be forced. The opposition to the Bill was not so much due to hatred of the actual provisions as fear of its consequences. The prospect of a Liberal Government being able to pass measures which for long have been part of their program, such as Home Rule, Welsh Disestablishment, or Electoral Reform, exasperated the party who had hitherto been secured against the passage of measures of capital importance introduced by their opponents. The anti-Home Rule cry and the supposed dictatorship of the Irish Nationalist leader were utilized to the full and were useful when constitutional and reasoned argument failed. At the same time as much as possible was made of the composite character of the majority supporting the Government.

Throughout the latter part of the controversy there is little doubt that the Conservatives would have been in a far stronger position had they acted as a united party with a definite policy and a strong leader ready at a moment’s notice to form an alternative Government. But they were deplorably led, they could agree on no policy, and their warmest supporters in the Press and in the country were the first to admit that the formation of an alternative Conservative Administration was unthinkable. Nevertheless, there could be no rival for the leadership. Mr. Balfour, aloof, indifferent, without enthusiasm, and without convictions, although discredited in the country and harassed in his attempts to save his party from Protection, remains in ability, Parliamentary knowledge, experience and skill, head and shoulders above his very mediocre band of colleagues in the House of Commons.

The Bill went up to the House of Lords, where Lord Morley, with the tact and skill of an experienced statesman and the unflinching firmness of a lifelong Liberal, conducted it through a very rough career. The Lords’ amendments were destructive of the principle, and therefore equivalent to rejection. But even a few days before those amendments were returned to the Commons the Conservatives refused to believe that the passage of the Bill in its original form was guaranteed. When at last it was brought home to them that, if necessary, the King would be advised to create a sufficient number of Peers to ensure the passage of the Bill into law, a howl of indignation went up. Scenes of confusion and unmannerly exhibitions of temper took place in the House of Commons. A party of revolt was formed among the Peers, and the Prime Minister was branded as a traitor who was guilty of treason and whose advice to the King in the words of the vote of censure was “a gross violation of constitutional liberty.”

As a matter of fact, Mr. Asquith was adhering very strictly to the letter and spirit of the Constitution. Lord Grey, who was confronted with a similar problem in 1832, very truly said: “If a majority of this House (House of Lords) is to have the power whenever they please of opposing the declared and decided wishes both of the Crown and the people without any means of modifying that power, then this country is placed entirely under the influence of an uncontrollable oligarchy. I say that if a majority of this House should have the power of acting adversely to the Crown and the Commons, and was determined to exercise that power without being liable to check or control, the Constitution is completely altered, and the Government of the country is not a limited monarchy; it is no longer, my Lords, the Crown, the Lords and Commons, but a House of Lords — a separate oligarchy — governing absolutely the others.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Arthur Ponsonby begins here. Sydney Brooks begins here. Captain George Swinton begins here.

More information here and here, and below.

|

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.