Canute, like a wise prince, was determined that the English, now deprived of all their dangerous leaders, should be reconciled to the Danish yoke, by the justice and impartiality of his administration.

Continuing Canute Becomes King of England,

our selection from History of England by David Hume published in 1754. The selection is presented in four easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Canute Becomes King of England.

Time: 1017

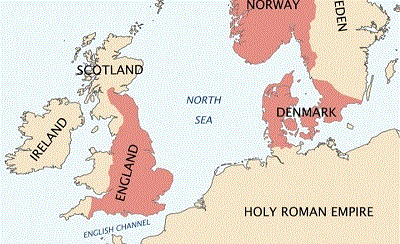

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

The English, who had been unable to defend their country and maintain their independency under so active and brave a prince as Edmund, could after his death expect nothing but total subjection from Canute, who, active and brave himself, and at the head of a great force, was ready to take advantage of the minority of Edwin and Edward, the two sons of Edmund. Yet this conqueror, who was commonly so little scrupulous, showed himself anxious to cover his injustice under plausible pretenses. Before he seized the dominions of the English princes, he summoned a general assembly of the states in order to fix the succession of the kingdom. He here suborned some nobles to depose that, in the treaty of Gloucester, it had been verbally agreed, either to name Canute, in case of Edmund’s death, successor to his dominions or tutor to his children — for historians vary in this particular; and that evidence, supported by the great power of Canute, determined the states immediately to put the Danish monarch in possession of the government. Canute, jealous of the two princes, but sensible that he should render himself extremely odious if he ordered them to be dispatched in England, sent them abroad to his ally, the King of Sweden, whom he desired, as soon as they arrived at his court, to free him, by their death, from all further anxiety. The Swedish monarch was too generous to comply with the request; but being afraid of drawing on himself a quarrel with Canute, by protecting the young princes, he sent them to Solomon, King of Hungary, to be educated in his court. The elder, Edwin, was afterward married to the sister of the King of Hungary; but the English prince dying without issue, Solomon gave his sister-in-law, Agatha, daughter of the emperor Henry II, in marriage to Edward, the younger brother; and she bore him Edgar, Atheling, Margaret, afterward Queen of Scotland, and Christina, who retired into a convent.

Canute, though he had reached the great point of his ambition in obtaining possession of the English crown, was obliged at first to make great sacrifices to it; and to gratify the chief of the nobility, by bestowing on them the most extensive governments and jurisdictions. He created Thurkill Earl or Duke of East Anglia — for these titles were then nearly of the same import — Yric of Northumberland, and Edric of Mercia; reserving only to himself the administration of Wessex. But seizing afterward a favorable opportunity, he expelled Thurkill and Yric from their governments, and banished them the kingdom; he put to death many of the English nobility, on whose fidelity he could not rely, and whom he hated on account of their disloyalty to their native prince. And even the traitor Edric, having had the assurance to reproach him with his services, was condemned to be executed and his body to be thrown into the Thames; a suitable reward for his multiplied acts of perfidy and rebellion.

Canute also found himself obliged, in the beginning of his reign, to load the people with heavy taxes in order to reward his Danish followers: he exacted from them at one time the sum of seventy-two thousand pounds, besides eleven thousand which he levied on London alone. He was probably willing, from political motives, to mulct severely that city, on account of the affection which it had borne to Edmund and the resistance which it had made to the Danish power in two obstinate sieges.* But these rigors were imputed to necessity and Canute, like a wise prince, was determined that the English, now deprived of all their dangerous leaders, should be reconciled to the Danish yoke, by the justice and impartiality of his administration. He sent back to Denmark as many of his followers as he could safely spare; he restored the Saxon customs in a general assembly of the states; he made no distinction between Danes and English in the distribution of justice; and he took care, by a strict execution of law, to protect the lives and properties of all his people. The Danes were gradually incorporated with his new subjects; and both were glad to obtain a little respite from those multiplied calamities from which the one, no less than the other, had, in their fierce contest for power, experienced such fatal consequences.

[* In one of these sieges Canute diverted the course of the Thames, and by that means brought his ships above London bridge.]

The removal of Edmund’s children into so distant a country as Hungary was, next to their death, regarded by Canute as the greatest security to his government: he had no further anxiety, except with regard to Alfred and Edward, who were protected and supported by their uncle Richard, Duke of Normandy. Richard even fitted out a great armament, in order to restore the English princes to the throne of their ancestors; and though the navy was dispersed by a storm, Canute saw the danger to which he was exposed from the enmity of so warlike a people as the Normans. In order to acquire the friendship of the duke, he paid his addresses to Queen Emma, sister of that prince, and promised that he would leave the children whom he should have by that marriage in possession of the Crown of England. Richard complied with his demand and sent over Emma to England, where she was soon after married to Canute. The English, though they disapproved of her espousing the mortal enemy of her former husband and his family, were pleased to find at court a sovereign to whom they were accustomed, and who had already formed connections with them; and thus Canute, besides securing, by this marriage, the alliance of Normandy, gradually acquired, by the same means, the confidence of his own subjects. The Norman prince did not long survive the marriage of Emma; and he left the inheritance of the duchy to his eldest son of the same name, who, dying a year after him without children, was succeeded by his brother Robert, a man of valor and abilities.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.