This series has four easy 5-minute installments. This first installment: Saxon Disunity and Dishonor.

Introduction

After the success of King Alfred over the Danes in the last quarter of the ninth century, England enjoyed a considerable respite from the invasions of the bold ravagers who had caused great suffering and loss to the country. This immunity of England seems to have been partly due to the fact that the Danish adventurers had gained a foothold in the north of France, where they found all the employment they needed in maintaining their establishments. Under the reign of Edward the Elder — chosen to succeed Alfred — the English enjoyed an interval of comparative peace and industry. During this time and under the following reigns, known as those of the Six Boy-Kings, the social side of life had an opportunity to develop from a semi-barbarous to a more civilized state. The bare and rough walls of hall and court were screened by tapestry hangings, often of silk, and elaborately ornamented with birds and flowers or scenes from the battlefield or the chase. Chairs and tables were skillfully carved and inlaid with different woods and, among the wealthier nobility, often decorated with gold and silver. Knives and spoons were now used at table — the fork was to come many long years later; golden ornaments were worn; and a variety of dishes were fashioned, often of precious metals, brass, and even bone. The bedstead became a household article, no longer looked upon with superstitious awe; and musical instruments — principally of the harp pattern — began to find favor in their eyes, and were passed round from hand to hand, like the drinking-bowl, at their rude festivals.

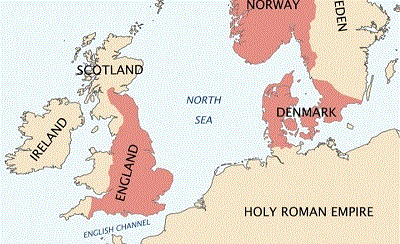

But toward the end of a century following the victories of Alfred the Danes again threatened an invasion, and in 981-991 they made several landings, in the latter year overrunning much territory. King Ethelred the Unready procured their departure by bribery, which led the Danes to repeat their visit the next year, following it up by a descent in force under King Sweyn of Denmark and Olaf of Norway. They defeated the English in battle and ravaged a great part of the country, exacting as before ruinous contributions from the already impoverished people. After the siege and taking of London, 1011-1013, the flight of the cowardly Ethelred to the court of Normandy, the sudden death of Sweyn, who had been but a few months before proclaimed King of England, and the return of Ethelred to his throne, Canute, the son of Sweyn, claimed the crown and ravaged the land in the manner and custom of his race. The complications and strife engendered by the rival claims of the Dane and Edmund Ironside, son of Ethelred, and which ended in the triumph of Canute and the complete subjugation of England, are hereinafter narrated by Hume, the English historian and later philosopher.

This selection is from History of England by David Hume published in 1754. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

David Hume (1711-1776) began his career writing his history. The book became a huge hit. The financial success from this book enabled him to launch his true calling, philosophy.

Time: 1017

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

The Danes had been established during a longer period in England than in France; though the similarity of their original language to that of the Saxons invited them to a more early coalition with the natives, they had hitherto found so little example of civilized manners among the English that they retained all their ancient ferocity, and valued themselves only on their national character of military bravery. The recent as well as more ancient achievements of their countrymen tended to support this idea; and the English princes, particularly Athelstan and Edgar, sensible of that superiority, had been accustomed to keep in pay bodies of Danish troops, who were quartered about the country and committed many violences upon the inhabitants. These mercenaries had attained to such a height of luxury, according to the old English writers, that they combed their hair once a day, bathed themselves once a week, changed their clothes frequently; and by all these arts of effeminacy, as well as by their military character, had rendered themselves so agreeable to the fair sex that they debauched the wives and daughters of the English and dishonored many families. But what most provoked the inhabitants was that, instead of defending them against invaders, they were ever ready to betray them to the foreign Danes, and to associate themselves with all straggling parties of that nation.

The animosity between the inhabitants of English and Danish race had, from these repeated injuries, risen to a great height, when Ethelred (1002), from a policy incident to weak princes, embraced the cruel resolution of massacring the latter throughout all his dominions. Secret orders were dispatched to commence the execution everywhere on the same day, and the festival of St. Brice, which fell on a Sunday, the day on which the Danes usually bathed themselves, was chosen for that purpose. It is needless to repeat the accounts transmitted concerning the barbarity of this massacre: the rage of the populace, excited by so many injuries, sanctioned by authority, and stimulated by example, distinguished not between innocence and guilt, spared neither sex nor age, and was not satiated without the tortures as well as death of the unhappy victims. Even Gunhilda, sister to the King of Denmark, who had married Earl Paling and had embraced Christianity, was, by the advice of Edric, Earl of Wilts, seized and condemned to death by Ethelred, after seeing her husband and children butchered before her face. This unhappy princess foretold, in the agonies of despair, that her murder would soon be avenged by the total ruin of the English nation.

Never was prophecy better fulfilled, and never did barbarous policy prove more fatal to the authors. Sweyn and his Danes, who wanted but a pretense for invading the English, appeared off the western coast, and threatened to take full revenge for the slaughter of their countrymen. Exeter fell first into their hands, from the negligence or treachery of Earl Hugh, a Norman, who had been made governor by the interest of Queen Emma. They began to spread their devastations over the country, when the English, sensible what outrages they must now expect from their barbarous and offended enemy, assembled earlier and in greater numbers than usual, and made an appearance of vigorous resistance. But all these preparations were frustrated by the treachery of Duke Alfric, who was entrusted with the command, and who, feigning sickness, refused to lead the army against the Danes, till it was dispirited and at last dissipated by his fatal misconduct. Alfric soon after died, and Edric, a greater traitor than he, who had married the King’s daughter and had acquired a total ascendant over him, succeeded Alfric in the government of Mercia and in the command of the English armies. A great famine, proceeding partly from the bad seasons, partly from the decay of agriculture, added to all the other miseries of the inhabitants. The country, wasted by the Danes, harassed by the fruitless expeditions of its own forces, was reduced to the utmost desolation, and at last submitted (1007) to the infamy of purchasing a precarious peace from the enemy by the payment of thirty thousand pounds.

The English endeavored to employ this interval in making preparations against the return of the Danes, which they had reason soon to expect. A law was made, ordering the proprietors of eight hides of land to provide each a horseman and a complete suit of armor, and those of three hundred and ten hides to equip a ship for the defense of the coast. When this navy was assembled, which must have consisted of near eight hundred vessels, all hopes of its success were disappointed by the factions, animosities, and dissensions of the nobility. Edric had impelled his brother Brightric to prefer an accusation of treason against Wolfnoth, governor of Sussex, the father of the famous earl Godwin; and that nobleman, well acquainted with the malevolence as well as power of his enemy, found no means of safety but in deserting with twenty ships to the Danes. Brightric pursued him with a fleet of eighty sail; but his ships being shattered in a tempest, and stranded on the coast, he was suddenly attacked by Wolfnoth, and all his vessels burned and destroyed. The imbecility of the King was little capable of repairing this misfortune. The treachery of Edric frustrated every plan for future defense; and the English navy, disconcerted, discouraged, and divided, was at last scattered into its several harbors.

It is almost impossible, or would be tedious, to relate particularly all the miseries to which the English were henceforth exposed. We hear of nothing but the sacking and burning of towns; the devastation of the open country; the appearance of the enemy in every quarter of the kingdom; their cruel diligence in discovering any corner which had not been ransacked by their former violence. The broken and disjointed narration of the ancient historians is here well adapted to the nature of the war, which was conducted by such sudden inroads as would have been dangerous even to a united and well-governed kingdom, but proved fatal where nothing but a general consternation and mutual diffidence and dissension prevailed. The governors of one province refused to march to the assistance of another, and were at last terrified from assembling their forces for the defense of their own province. General councils were summoned; but either no resolution was taken or none was carried into execution. And the only expedient in which the English agreed was the base and imprudent one of buying a new peace from the Danes, by the payment of forty-eight thousand pounds.

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.