The historical essence of the matter is that an immense body of restless, uncivilized Germans could not abide permanently in the center of Roman provinces in a semi-dependent, ill-defined relation to the Roman government.

Continuing Final Division of Roman Empire,

our selection from History of the Later Roman Empire by John B. Bury published in 1889. The selection is presented in six easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Final Division of Roman Empire.

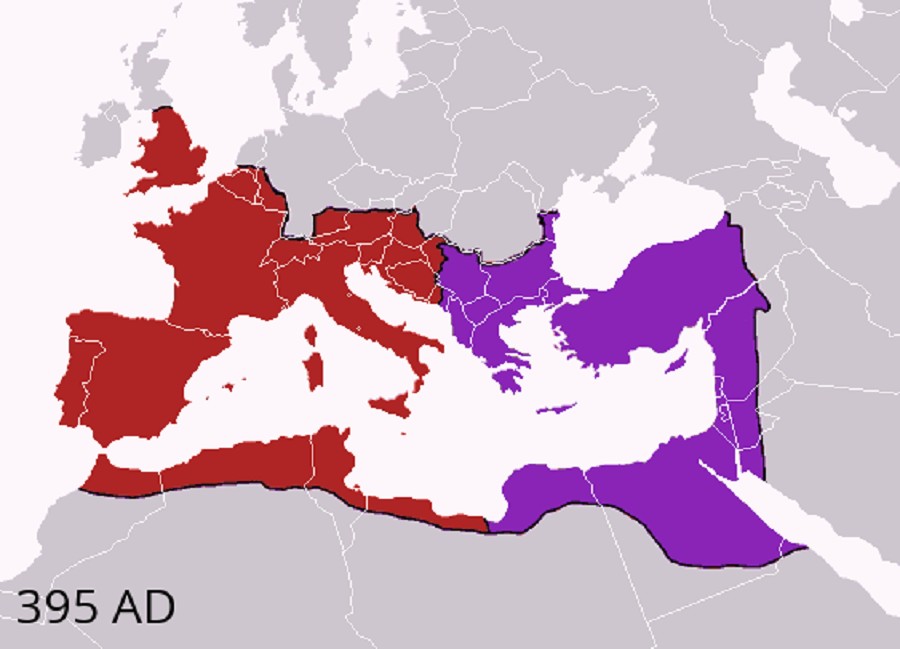

Time: 395

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

The causes of discontent which led to their revolt are not quite clear; but it seems that Arcadius refused to give them certain grants of money which had been allowed them by his father, and, as has been suggested, they probably expected that favor would wane and influence decrease now that the “friend of Goths” was dead, and consequently determined to make themselves heard and felt. To this must be added that their most influential chieftain, Alaric, called Baltha (“the Bold”), desired to be made a commander-in-chief, magister militum, and was offended that he had been passed over.

However this may be, the historical essence of the matter is that an immense body of restless, uncivilized Germans could not abide permanently in the center of Roman provinces in a semi-dependent, ill-defined relation to the Roman government; the West Goths had not yet found their permanent home. Under the leadership of Alaric they raised the ensign of revolt and spread desolation in the fields and homesteads of Macedonia, Moesia, and Thrace, even advancing close to the walls of Constantinople. They carefully spared certain estates outside the city, belonging to the prefect Rufinus, but this policy does not seem to have been adopted with the same motive that caused Archidamus to spare the lands of Pericles. Alaric may have wished not to render Rufinus suspected, but to conciliate his friendship and obtain thereby more favorable terms. Rufinus actually went to Alaric’s camp, dressed as a Goth, but the interview led to nothing.

It was impossible to take the field against the Goths, because there were no forces available, as the eastern armies were still with Stilicho in the West. Arcadius therefore was obliged to summon Stilicho to send or bring them back immediately, to protect his throne. This summons gave that general the desired opportunity to interfere in the politics of Constantinople; and having with energetic celerity arranged matters on the Gallic frontier, he marched overland through Illyricum and confronted Alaric in Thessaly, whither the Goth had traced his devastating path from the Propontis.

It appears that Stilicho’s behavior is quite as open to the charges of ambition and artfulness as the behavior of Rufinus, for I do not perceive how we can strictly justify his detention of the forces, which ought to have been sent back to defend the provinces of Arcadius at the very beginning of the year. Stilicho’s march to Thessaly can scarcely have taken place before October, and it is hard to interpret this long delay in sending back the troops, over which he had no rightful authority, if it were not dictated by a wish to implicate the government of New Rome in difficulties and render his own intervention necessary.

We are told, too, that he selected the best soldiers from the eastern regiments and enrolled them in the western corps. If we adopted the Cassian maxim, Cui bono fuerit, we should be inclined to accuse Stilicho of having been privy to the revolt of Alaric; such a supposition would at least be far more plausible than the calumny which was circulated charging Rufinus with having stirred up the Visigoths. For such a supposition, too, we might find support in the circumstance that the estates of Rufinus were spared by the soldiers of Alaric; it would be intelligible that Stilicho suggested the plan in order to bring odium upon Rufinus. To such a conjecture, finally, certain other circumstances, soon to be related, point: but it remains nothing more than a suspicion.

It seems that before Stilicho arrived Alaric had experienced a defeat at the hands of garrison soldiers in Thessaly; at all events he shut himself up in a fortified camp and declined to engage with the Roman general. In the meantime Rufinus induced Arcadius to send a peremptory order to Stilicho to dispatch the eastern troops to Constantinople and depart himself whence he had come; the Emperor resented, or pretended to resent, the presence of his cousin as an officious interference. Stilicho yielded so readily that his willingness seems almost suspicious; but we shall probably never know whether he was responsible for the events that followed. He consigned the eastern soldiers to the command of a Gothic captain, Gainas, and himself departed to Salona, allowing Alaric to proceed on his wasting way into the lands of Hellas.

Gainas and his soldiers marched by the Via Egnatia to Constantinople, and it was arranged that, according to a usual custom, the Emperor and his court should come forth from the city to meet the army in the Campus Martius, which extended on the west side of the city near the Golden Gate. We cannot trust the statement of a hostile writer that Rufinus actually expected to be created augustus on this occasion, and appeared at the Emperor’s side prouder and more sumptuously arrayed than ever; we only know that he accompanied Arcadius to meet the army.

It is said that, when the Emperor had saluted the troops, Rufinus advanced and displayed a studied affability and solicitude to please toward even individual soldiers. They closed in round him as he smiled and talked, anxious to secure their good-will for his elevation to the throne, but just as he felt himself very nigh to supreme success, the swords of the nearest were drawn, and his body, pierced with wounds, fell to the ground. His head, carried through the streets, was mocked by the people, and his right hand, severed from the trunk, was presented at the doors of houses with the request: “Give to the insatiable!”

We can hardly suppose that the lynching of Rufinus was the fatal inspiration of a moment, but whether it was proposed or approved of by Stilicho, or was a plan hatched among the soldiers on their way to Constantinople, is uncertain. One might even conjecture that the whole affair was the result of a prearrangement between Stilicho and the party in Byzantium, which was adverse to Rufinus and led by the eunuch Eutropius but there is no evidence. Our knowledge of this scene unfortunately depends on a partial and untrustworthy writer, who, moreover, wrote in verse — the poet Claudian.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.