Today’s installment concludes Final Division of Roman Empire,

our selection from History of the Later Roman Empire by John B. Bury published in 1889.

If you have journeyed through the installments of this series so far, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of six thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Final Division of Roman Empire.

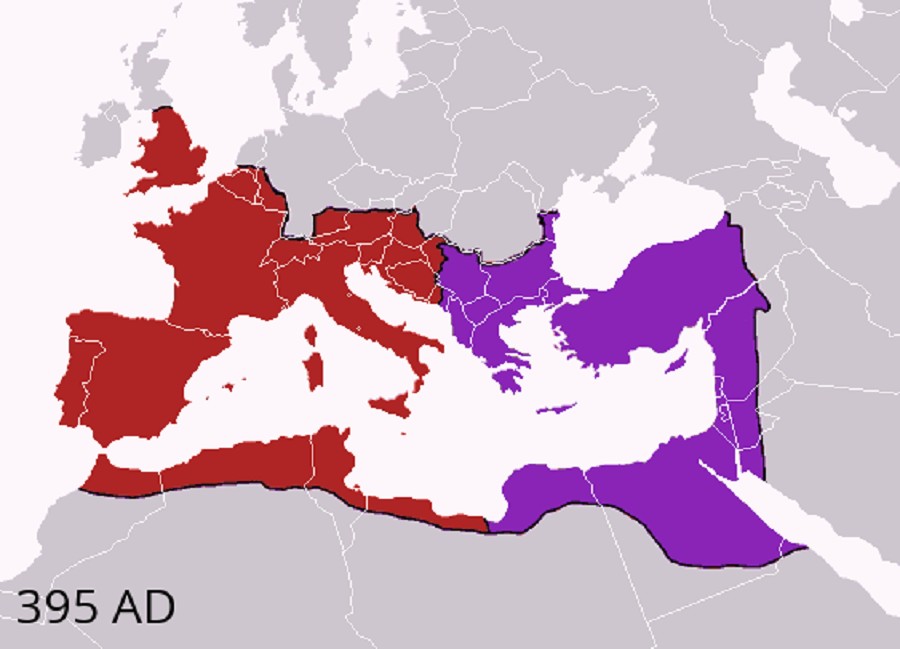

Time: 395

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

The situation was now complicated by a revolt in Africa, which eventually proved highly fortunate for the glory and influence of Stilicho.

Eighteen years before, the Moor Firmus had made an attempt to create a kingdom for himself in the African provinces (A.D. 379), and had been quelled by the arms of Theodosius, who received important assistance from Gildo, the brother and enemy of Firmus. Gildo was duly rewarded. He was finally military commander, or Count, of Africa, and his daughter Salvina was united in marriage to a nephew of the empress Ælia Flaccilla. But the faith of the Moors was as the faith of Carthaginians. Gildo refused to send aid to Theodosius in his expedition against Eugenius.

After Theodosius’ death he prepared to take a more positive attitude, and he engaged numerous African nomad tribes to support him in his revolt. The strained relations between Old and New Rome, which did not escape his notice, suggested to him that his rebellion might assume the form of a transition from the sovereignty of Honorius to the sovereignty of Arcadius. He knew that if he were dependent only on New Rome he would be practically independent. He entered accordingly into communication with the government of Arcadius, but the negotiations came to nothing. It appears that Gildo demanded that Lybia should be consigned to his rule, and he certainly took possession of it. It also appears that embassies on the subject passed between Italy and Constantinople, and that Symmachus the orator was one of the ambassadors. But it is certain that Arcadius did not in any way assist Gildo, and the comparatively slight and moderate references which the hostile Claudius makes to the hesitating attitude of New Rome indicate that the government of Alexandrius did not behave very badly after all.

We need not go into the details of the Gildonic war, through which Stilicho won well-deserved laurels, although he did not take the field himself. What made the revolt of the Count of Africa of such great moment was the fact that the African provinces were the granary of Old Rome, as Egypt was the granary of New Rome. By stopping the supplies of corn, Gildo might hope to starve out Italy. The prompt action and efficient management of Stilicho, however, prevented any catastrophe; for ships from Gaul and from Spain, laden with corn, appeared in the Tiber, and Rome was supplied during the winter months. Early in 398 a fleet sailed against the tyrant, whose hideous cruelties and oppressions were worthy of his Moorish blood; and it is a curious fact that this fleet was under the command of Mascezel, Gildo’s brother, who was now playing the same part toward Gildo that Gildo had played toward his brother Firmus. The undisciplined nomadic army of the rebel was scattered without labor at Ardalio, and Africa was delivered from the Moor’s reign of ruin and terror, to which Roman rule, with all its fiscal sternness, was peace and prosperity.

This subjugation of the man whom the senate of Old Rome had pronounced a public enemy redounded far and wide to the glory of the man whom the senate of New Rome had proclaimed a public enemy. And in the mean time Stilicho’s position had become still more splendid and secure by the marriage of his daughter Maria with the emperor Honorius (398), for which an epithalamium was written by Claudian, who, as we might expect, celebrates the father-in-law as expressly as the bridal pair. The Gildonic war also supplied, we need hardly remark, a grateful material for his favorite theme; and the year 400, to which Stilicho gave his name of consul, inspired an enthusiastic effusion.

It may seem strange that now, almost at the zenith of his fame, the father-in-law of the Emperor and the hero of the Gildonic war did not make some attempt to carry out his favorite project of interfering with the government of the eastern provinces. But there are two considerations which may help to explain this.

In the first place Stilicho himself was not the man of indomitable will who forms a project and carries it through; he was a man rather of that ambitious but hesitating character which Mommsen attributes to Pompey. He was half a Roman and half a barbarian; he was half strong and half weak; he was half patriotic and half selfish. His intentions were unscrupulous, but he was almost afraid of them. Besides this, his wife, Serena, probably endeavored to check his policy of discord and maintain unity in the Theodosian house. In the second place, it is sufficiently probable that he was in constant communication with Gainas, the German general of the eastern armies and chief representative of the German interests in the realm of Arcadius, and that Gainas was awaiting his time for an outbreak, by which Stilicho hoped to profit and execute his designs. He had no excuse for interference, and he was willing to wait. His inactive policy of the next two years must not be taken to indicate that he cherished no ambitious projects.

The Germans looked up to Stilicho as the most important German in the empire; their natural protector and friend, while there was a large Roman faction opposed to him as a foreigner. But as yet this faction was not strong enough to overpower him. It is remarkable that his fall was finally brought about by the influence of a palace official (A.D. 408), while the fall of his rival Eutropius, which occurred far sooner (A.D. 399), was brought about by the compulsion of a German general. These facts indicate that the two dangers to which I have already called attention — the preponderating influence of chamberlains and eunuchs — were mutually checks on each other.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on Final Division of Roman Empire by John B. Bury from his book History of the Later Roman Empire published in 1889. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information on Final Division of Roman Empire here and here and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.