The senate accordingly passed a resolution declaring Stilicho a public enemy.

Continuing Final Division of Roman Empire,

our selection from History of the Later Roman Empire by John B. Bury published in 1889. The selection is presented in six easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Final Division of Roman Empire.

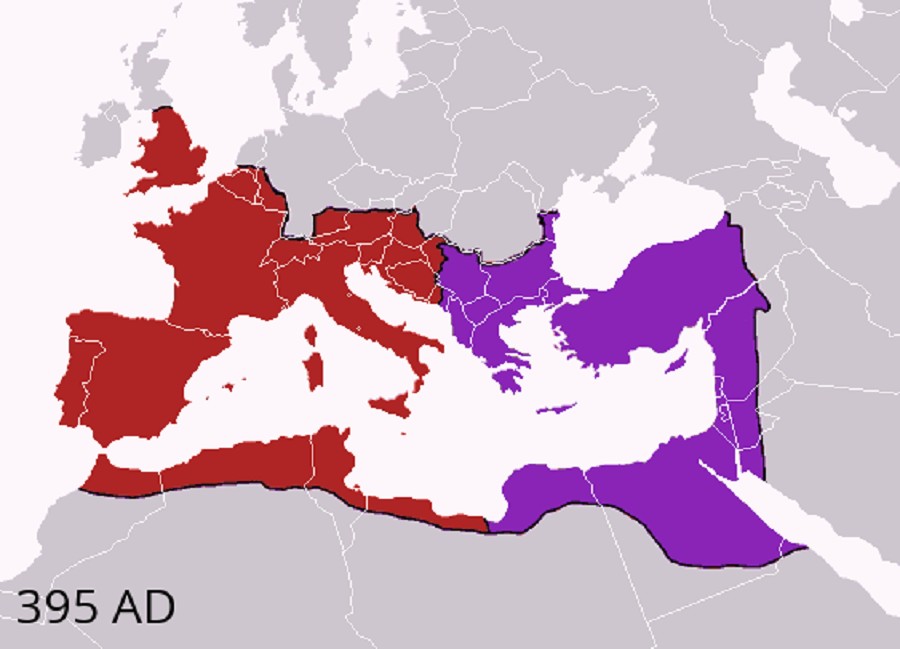

Time: 395

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

The eunuch won considerable odium in the first year of his power (396) by bringing about the fall of two men of distinction — Abundantius, to whose patronage he owed his rise in the world, and Timasius, who had been the commander-general in the East. An account of the manner in which the ruin of the latter was wrought will illustrate the sort of intrigues that were spun at the Byzantine court.

Timasius had brought with him from Sardis a Syrian sausage-seller, named Bargus, who, with native address, had insinuated himself into his good graces and obtained a subordinate command in the army. The prying omniscience of Eutropius discovered that, years before, this same Bargus had been forbidden to enter Constantinople for some misdemeanor, and by means of this knowledge he gained an ascendency over the Syrian, and compelled him to accuse his benefactor, Timasius, of a treasonable conspiracy, supporting the charge by forgeries. The accused was tried, condemned, and banished to the Lybian oasis, a punishment equivalent to death; he was never heard of more. Eutropius, foreseeing that the continued existence of Bargus might at some time compromise himself, suborned his wife to lodge very serious charges against her husband, in consequence of which he was put to death. Whether Eutropius then got rid of the wife we are not informed.

Among the adherents of Eutropius, who were equally numerous and insincere, two were of especial importance — Osius, who had risen from the post of a cook to be count of the sacred largesses, and finally master of the offices, and Leo, a soldier, corpulent and good-humored, who was known by the sobriquet of Ajax, a man of great body and little mind, fond of boasting, fond of eating, fond of drinking, and fond of women.

On the other hand, Eutropius had many enemies, and enemies in two different quarters. Romans of the stamp of Timasius and Aurelian were naturally opposed to the supremacy of an emasculated chamberlain; while, as we shall see subsequently, the German element in the empire, represented by Gainas, was also inimical. It seems certain that a serious confederacy was formed in the year 397, aiming at the overthrow of Eutropius. Though this is not stated by any writer, it seems an inevitable conclusion from the law which was passed in the autumn of that year, assessing the penalty of death to anyone who had conspired “with soldiers or private persons, including barbarians,” against the lives “of illustres who belong to our consistory or assist at our counsels,” or other senators, such a conspiracy being considered equivalent to treason. Intent was to be regarded as equivalent to crime, and not only did the individual concerned incur capital punishment, but his descendants were visited with disfranchisement.

It is generally recognized that this law was an express palladium for chamberlains; but surely it must have been suggested by some actually formed conspiracy, of which Eutropius discovered the threads before it was carried out. The particular mention of soldiers and barbarians points to a particular danger, and we may suspect that Gainas, who afterward brought about the fall of Eutropius, had some connection with it.

While the eunuch was sailing in the full current of success at Byzantium, the Vandal Stilicho was enjoying an uninterrupted course of prosperity in the somewhat less stifling air of Italy. The poet Claudian, who acted as a sort of poet-laureate to Honorius, was really an apologist for Stilicho, who patronized and paid him. Almost every public poem he produced is an extravagant panegyric on that general, and we cannot but suspect that many of his utterances were direct manifestoes suggested by his patron. In the panegyric in honor of the third consulate of Honorius (396), which, composed soon after the death of Rufinus, breathes a spirit of concord between East and West, the writer calls upon Stilicho “to protect with his right hand the two brothers” (geminos dextra tu protege fratres).

Such lines as this are written to put a certain significance on Stilicho’s policy. In the panegyric in honor of the fourth consulate of Honorius (398) he gives an absolutely false and misleading account of Stilicho’s expedition to Greece two years before, an account which no allowance for poetical exaggeration can defend. At the same time, he extols Honorius with the most absurd eulogiums, and overwhelms him with the most extravagant adulations, making out the boy of fourteen to be greater than his father and grandfather. If Claudian were not a poet, we should say that he was a most outrageous liar. We are therefore unable to accord him the smallest credit when he boasts that the subjects in the western provinces are not oppressed by heavy taxes and that the treasury is not replenished by extortion.

Stilicho and Eutropius had shaken hands over the death of Rufinus but the good understanding was not destined to last longer than the song of triumph. We cannot justly blame Eutropius for this. No minister of Arcadius could regard with good-will or indifference the desire of Stilicho to interfere in the affairs of New Rome; for this desire cannot be denied, even if one do not accept the theory that the scheme of detaching Illyricum from Arcadius’ dominion was entertained by him at as early a date as 396. His position as master of soldier in Italy gave him no power in other parts of the empire; and the attitude which he assumed as an elderly relative, solicitously concerned for the welfare of his wife’s young cousin, in obedience to the wishes of that cousin’s father, was untenable, when it led him to exceed the acts of a strictly private friendship.

We can then well understand the indignation felt at New Rome, not only by Eutropius, but probably also by men of a quite different faction, when the news arrived that Stilicho purposed to visit Constantinople to set things in order and arrange matters for Arcadius. Such officiousness was intolerable, and it was plain that the strongest protest must be made against it. The senate accordingly passed a resolution declaring Stilicho a public enemy. This action of the senate is very remarkable, and its signification is not generally perceived. If the act had been altogether due to Eutropius, it would surely have taken the form of an imperial decree. Eutropius would not have resorted to the troublesome method of bribing or threatening the whole senate even if he had been able to do so. We must conclude then that the general feeling against Stilicho was strong, and we must confess naturally strong.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.