The Emperor, who, living in the retirement of his palace, was tempted to trust less to his eyes than his ears, and saw too little of public affairs.

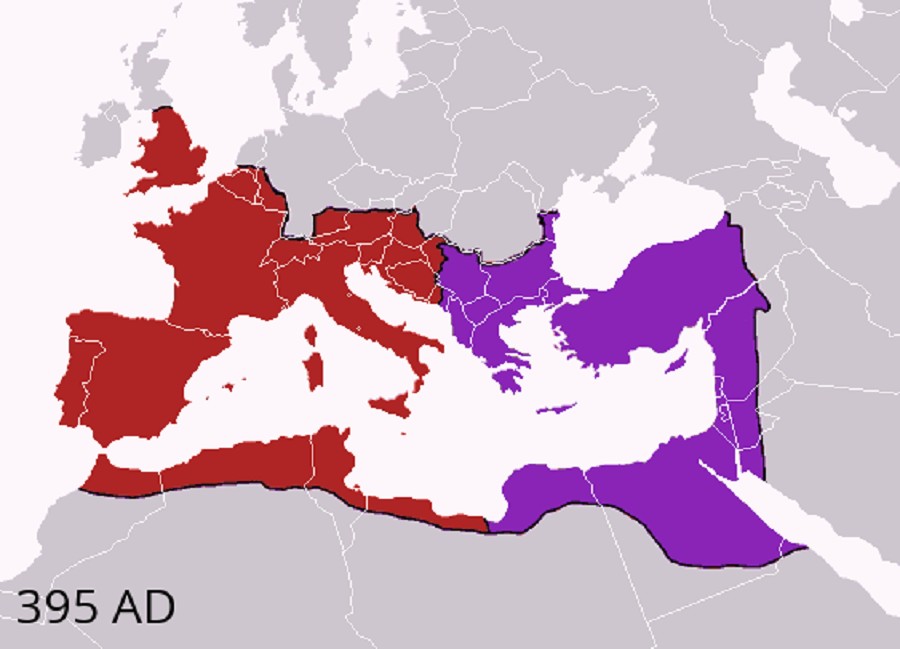

Continuing Final Division of Roman Empire,

our selection from History of the Later Roman Empire by John B. Bury published in 1889. The selection is presented in six easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Final Division of Roman Empire.

Time: 395

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

The Huns, however, were not the only depredators at whose hands the provinces of Asia Minor and Syria suffered. There were other enemies within, whose ravages were constant, while the expedition of the Huns from without occurred only once. These enemies were the freebooters who dwelt in the Isaurian mountains, wild and untamed in their secure fastnesses. Ammianus Marcellinus describes picturesquely the habits of these sturdy robbers. They used to descend from the difficult mountain slopes like a whirlwind to places on the sea-shore, where in hidden ways and glens they lurked till the fall of night, and in the light of the crescent moon watched until the mariners riding at anchor slept; then they boarded the vessels, killed and plundered the crews. Thus, the coast of Isauria was like a deadly shore of Sciron; it was avoided by sailors, who made a practice of putting in at the safer ports of Cyprus.

The Isaurians did not always confine their land expeditions to the surrounding provinces of Cilicia and Pamphylia; they penetrated, in A.D. 403, northward to Cappadocia and Pontus, or southward to Syria and Palestine; and the whole range of the Taurus, as far as the confines of Syria, seems to have been their spacious habitation. An officer named Arbacazius was intrusted by Arcadius with an office similar in object to that which, four and a half centuries ago, had been assigned to Pompeius; but, though he quelled the spirits of the freebooters for a moment, Arbacazius did not succeed in eradicating the lawless element, in the same way as Pompeius had succeeded in exterminating the piracy which in his day infested the same regions. In the years 404 and 405 Cappadocia was overrun by the robber bands.

Meanwhile, after the death of Rufinus, the weak emperor Arcadius passed under the influence of the eunuch Eutropius, who, in unscrupulous greed of money, resembled Rufinus and many other officials of the time, and, like Rufinus, has been painted far blacker than he really was. All the evil things that were said by his enemies of Rufinus were said of Eutropius by his enemies; but in reading of the enormities of the latter we must make great allowance for the general prejudice existing against a person with Eutropius’ physical disqualifications.

Eutropius naturally looked on the praetorian prefects, the most powerful men in the administration next to the Emperor, with jealousy and suspicion, as dangerous rivals. It was his interest to reduce their power and to raise the dignity of his own office to an equality with theirs. To his influence, then, we are probably justified in ascribing two innovations which were made by Arcadius. The administration of the cursus publicus, or office of postmaster-general, was transferred from the praetorian prefects to the master of offices, and the same transference was made in regard to the manufactories of arms. On the other hand, the grand chamberlain, praepositus sacri cubiculi, was made an illustris, equal in rank to the praetorian prefects. Both these innovations were afterward altered.

The general historical import of the position of Eutropius is that the empire was falling into a danger, by which it had been threatened from the outset, and which it had been ever trying to avoid. We may say that there were two dangers which constantly impended over the Roman Empire from its inauguration by Augustus to its redintegration by Diocletian — a Scylla and Charybdis, between which it had to steer. The one was a cabinet of imperial freedmen, the other was a military despotism. The former danger called forth, and was counteracted by, the creation of a civil service system, to which Hadrian perhaps made the most important contributions, and which was finally elaborated by Diocletian, who at the same time averted the other danger by separating the military and civil administrations. But both dangers revived in a new form. The danger from the army became danger from the Germans, who preponderated in it; and the institution of court ceremonial tended to create a cabinet of chamberlains and imperial dependents.

This oriental ceremonial, so marked a feature of late “Byzantinism,” involved, as one of its principles, difficulty of access to the Emperor, who, living in the retirement of his palace, was tempted to trust less to his eyes than his ears, and saw too little of public affairs. Diocletian appreciated this disadvantage himself, and remarked that the sovereign, shut up in his palace, cannot know the truth, but must rely on what his attendants and officers tell him. We may also remark that absolute monarchy, by its very nature, tends in this direction; for absolute monarchy naturally tends to a dynasty, and a dynasty implies that there must sooner or later come to the throne weak men, inexperienced in public affairs, reared up in an atmosphere of flattery and illusion, easily guided by intriguing chamberlains and eunuchs. Under such conditions, then, aulic cabals and chamber cabinets are sure to become dominant sometimes. Diocletian, whose political insight and ingenuity were remarkable, tried to avoid the dangers of a dynasty by his artificial system, but artifice could not contend with success against nature.

The greatest blot on the ministry of Eutropius — for, as he was the most trusted adviser of the Emperor, we may use the word ministry — was the sale of offices, of which Claudian gives a vivid and exaggerated account. This was a blot, however, that stained other men of those days as well as Eutropius, and we must view it rather as a feature of the times than as a personal enormity. Of course, the eunuch’s spies were ubiquitous; of course, informers of all sorts were encouraged and rewarded. All the usual stratagems for grasping and plundering were put into practice.

The strong measures that a determined minister was ready to take for the mere sake of vengeance may be exemplified by a treatment which the whole Lycian province received at the hands of Rufinus. On account of a single individual, Tatian, who had offended that minister, all the provincials were excluded from public offices. After the death of Rufinus, the Lycians were relieved from these disabilities; but the fact that the edict of emancipation expressly enjoins “that no one henceforward venture to wound a Lycian citizen with a name of scorn” shows what a serious misfortune their degradation was.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.