It was not only the European parts of Arcadius’ dominions that were ravaged in 395, by the fire and sword of barbarians.

Continuing Final Division of Roman Empire,

our selection from History of the Later Roman Empire by John B. Bury published in 1889. The selection is presented in six easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Final Division of Roman Empire.

Time: 395

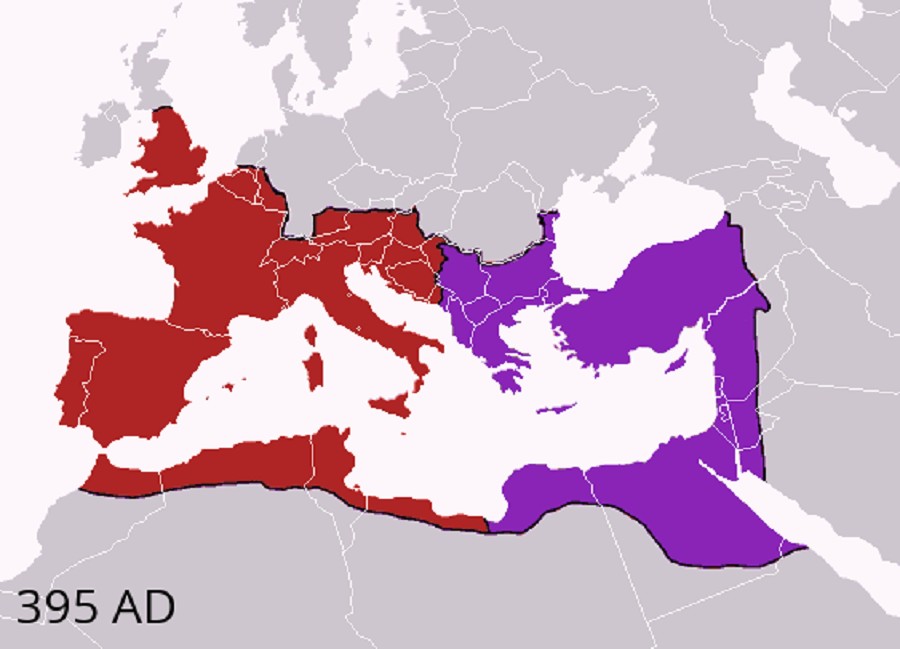

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

He enjoyed the patronage of Stilicho, and his poems Against Rufinus, Against Eutropius, and On the Gothic War are a glorification of his patron’s splendid virtues. Stilicho and Rufinus he paints as two opposite forces, the force of good and the force of evil, like the principles of the Manicheans.

Rufinus is the terrible Pytho, the scourge of the world; Stilicho is the radiant Apollo, the deliverer of mankind. Rufinus is a power of darkness, whose tartarean wickedness surpasses even the wickedness of the Furies of hell; Stilicho is an angel of light. In the works of a poet whose leading idea was so extravagant, we can hardly expect to find much fair historical truth; it is, as a rule, only accidental references and allusions that we can accept, unless other authorities confirm his statements. Yet even modern writers, who know well how cautiously Claudian must be used, have been unconsciously prejudiced in favor of Stilicho and against Rufinus.

We must return to the movements of Alaric, who had entered the regions of classical Greece, for which he showed scant respect. The commander of the garrison at Thermopylae, and the proconsul of Achaia, offered no resistance, and the West Goths entered Boeotia, where Thebes alone escaped their devastation. They occupied the Piraeus but Athens itself was spared and Alaric was entertained as a guest in the city of Athene. But the great temple of the mystic goddesses Demeter and Persephone, at Eleusis, was burned down by the irreverent barbarians; Megara, the next place on their southward route, fell; then Corinth, Argos, and Sparta.

But when they reached Elis they were confronted by an unexpected opponent. Stilicho had returned from Italy, by way of Salona, which he reached by sea, to stay the hand of the invader. He blockaded him in the plain of Pholoe, but for some reason, not easily comprehensible, he did not press his advantage, and set free the hordes of the Visigothic land pirates to resume their career of devastation. He went back to Italy, and Alaric returned, plundering as he went, to Illyricum and Thrace, where he made terms with the government of New Rome, and received the desired title of magister militum per Illyricum. No one will suppose that Stilicho went all the way from Italy to the Peloponnesus, and then, although he had Alaric practically at his mercy, retreated, leaving matters just as they were, without some excellent reason.

If he had genuinely wished to deliver the distressed countries and assist the emperor Arcadius, he would not have acted in this ineffectual manner. And it is difficult to see that his conduct is explained by assuming that he was not willing, by a complete extermination of the Goths, to enable Arcadius to dispense with his help in future. In that case, what did he gain by going to the Peloponnesus at all? Or we might ask, if he wished Arcadius to summon his assistance from year to year, is it likely that he would have adopted the method of rendering no assistance whatever? But, above all, the question occurs, what pleasure would it have been to the general to look forward to being called upon again and again to take the field against the Visigoths?

It seems evident that Stilicho and Alaric made at Pholoe some secret and definite arrangement, which conditioned Stilicho’s departure, and that this arrangement was conducive to the interests of Stilicho, who was in the position of advantage, and at the same time not contrary to the interests of Alaric, for otherwise Stilicho could not have been sure that the agreement would be carried out. What this secret compact was can only be a matter of conjecture; but I would suggest that Stilicho had already formed the plan of creating his son Eucherius emperor, and that he designed the Balkan peninsula to be the dominion over which Eucherius should hold sway. His conduct becomes perfectly explicable if we assume that by a secret agreement he secured Alaric’s assistance for the execution of this scheme, which the preponderance of Gothic power in Illyricum and Thrace would facilitate.

It was not only the European parts of Arcadius’ dominions that were ravaged in 395, by the fire and sword of barbarians. In the same year hordes of trans-Caucasian Huns poured through the Caspian gates, and, rushing southward through the provinces of Mesopotamia, carried desolation into Syria. St. Jerome was in Palestine at this time, and in two of his letters we have the account of an eye-witness:

As I was searching for an abode worthy of such a lady (Fabiola, his friend), behold, suddenly messengers rush hither and thither, and the whole East trembles with the news that from the far Maeotis, from the land of the ice-bound Don and the savage Massagetæ, where the strong works of Alexander on the Caucasian cliffs keep back the wild nations, swarms of Huns had burst forth, and, flying hither and thither, were scattering slaughter and terror everywhere. The Roman army was at that time, absent in consequence of the civil wars in Italy…. May Jesus protect the Roman world in future from such beasts! They were everywhere, when they were least expected, and their speed outstripped the rumor of their approach; they spared neither religion nor dignity nor age; they showed no pity to the cry of infancy.

“Babes, who had not yet begun to live, were forced to die; and, ignorant of the evil that was upon them, as they were held in the hands and threatened by the swords of the enemy, there was a smile upon their lips. There was a consistent and universal report that Jerusalem was the goal of the foes, and that on account of their insatiable lust for gold they were hastening to this city. The walls, neglected by the carelessness of peace, were repaired. Antioch was enduring a blockade. Tyre, fain to break off from the dry land, sought its ancient island. Then we too were constrained to provide ships, to stay on the sea-shore, to take precautions against the arrival of the enemy, and, though the winds were wild, to fear a shipwreck less than the barbarians — making provision not for our own safety so much as for the chastity of our virgins.” In another letter, speaking of these “wolves of the north,” he says: “How many monasteries were captured? The waters of how many rivers were stained with human gore? Antioch was besieged and the other cities, past which the Halys, the Cydnus, the Orontes, the Euphrates flow. Herds of captives were dragged away; Arabia, Phoenicia, Palestine, Egypt, were led captive by fear.”

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.