This series has nine easy 5-minute installments. This first installment: A Class of Babblers, A School for Lies and Scandal.

Introduction

When Alexander, having returned from his campaign against the barbarians of the North, had suppressed a revolt which meanwhile had broken out in Greece, he found himself free for undertaking those great foreign conquests which he had planned. When he left Greece to conquer the world, he said farewell to his own country forever. Crossing the Hellespont into Asia Minor with a small but well equipped and disciplined army, he advanced unopposed until he reached the river Granicus, where he found himself confronted with a Persian host. Upon this army he inflicted a defeat so signal as to bring at once to submission nearly the whole of Asia Minor. He next advanced into Syria and met the Persian king, Darius III, who in person commanded an immense body of soldiers, against which the young conqueror fought at Issus, winning a decisive victory. He not only captured the Persian camp, but also secured the King’s treasures and took his family prisoners. From this time Alexander held complete mastery of the western dominions of Darius, whom the conqueror afterward dethroned.

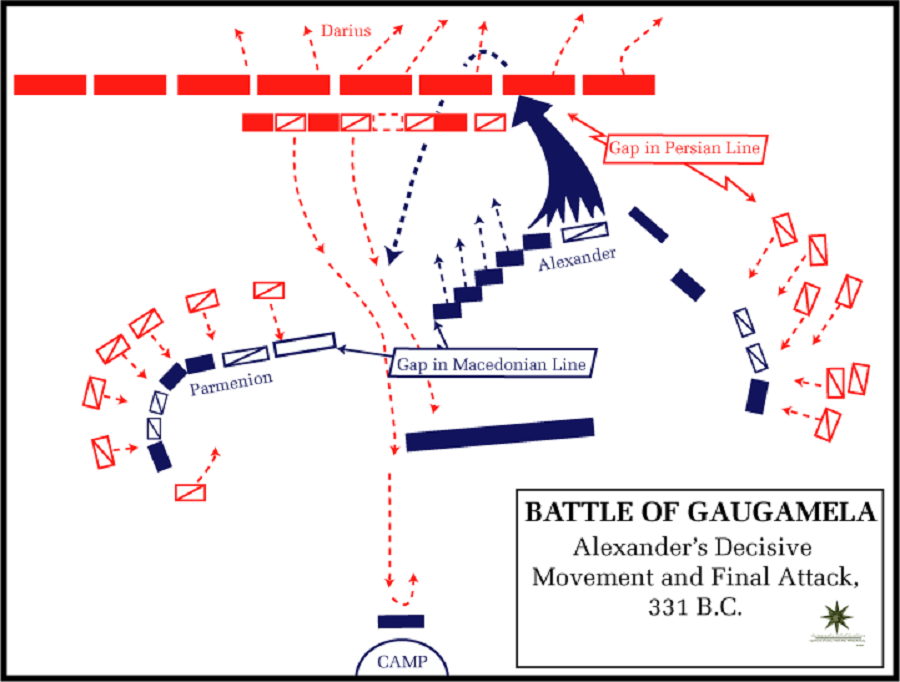

After he had next invaded and subjugated Egypt and there founded the city of Alexandria, he pursued King Darius, who had taken flight, into the very heart of his empire, where the Persian monarch, on the plains of Gaugamela, near the village of Arbela, made his last stand against his invincible foe. Of the battle which proved the death-blow of the Persian empire, Creasy’s narrative furnishes a realistic description.

This selection is from Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World by Sir Edward S. Creasy published in 1851. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Sir Edward S. Creasy (1812-1878) was an English historian. His Fifteen Battles book was his magnum opus.

Time: 331 BC

Place: East of Mosul, Iraq

CC BY-SA 3.0 image from Wikipedia.

A long and not uninstructive list might be made out of illustrious men whose characters have been vindicated during recent times from aspersions which for centuries had been thrown on them. The spirit of modern inquiry, and the tendency of modern scholarship, both of which are often said to be solely negative and destructive, have, in truth, restored to splendor, and almost created anew, far more than they have assailed with censure or dismissed from consideration as unreal.

The truth of many a brilliant narrative of brilliant exploits has of late years been triumphantly demonstrated, and the shallowness of the skeptical scoffs with which little minds have carped at the great minds of antiquity has been in many instances decisively exposed. The laws, the politics, and the lines of action adopted or recommended by eminent men and powerful nations have been examined with keener investigation and considered with more comprehensive judgment than formerly were brought to bear on these subjects. The result has been at least as often favorable as unfavorable to the persons and the states so scrutinized, and many an oft-repeated slander against both measures and men has thus been silenced, we may hope forever.

The veracity of Herodotus, the pure patriotism of Pericles, of Demosthenes, and of the Gracchi, the wisdom of Clisthenes and of Licinius as constitutional reformers, may be mentioned as facts which recent writers have cleared from unjust suspicion and censure. And it might be easily shown that the defensive tendency which distinguishes the present and recent great writers of Germany, France, and England has been equally manifested in the spirit in which they have treated the heroes of thought and heroes of action who lived during what we term the Middle Ages, and whom it was so long the fashion to sneer at or neglect.

The name of the victor of Arbela has led to these reflections; for, although the rapidity and extent of Alexander’s conquests have through all ages challenged admiration and amazement, the grandeur of genius which he displayed in his schemes of commerce, civilization, and of comprehensive union and unity among nations, has, until lately, been comparatively unhonored. This long-continued depreciation was of early date. The ancient rhetoricians — a class of babblers, a school for lies and scandal, as Niebuhr justly termed them — chose, among the stock themes for their commonplaces, the character and exploits of Alexander.

They had their followers in every age and, until a very recent period, all who wished to “point a moral or adorn a tale,” about unreasoning ambition, extravagant pride, and the formidable frenzies of free will when leagued with free power, have never failed to blazon forth the so-called madman of Macedonia as one of the most glaring examples. Without doubt, many of these writers adopted with implicit credence traditional ideas, and supposed, with uninquiring philanthropy, that in blackening Alexander they were doing humanity good service. But also, without doubt, many of his assailants, like those of other great men, have been mainly instigated by “that strongest of all antipathies, the antipathy of a second-rate mind to a first-rate one,” and by the envy which talent too often bears to genius.

Arrian, who wrote his history of Alexander when Hadrian was emperor of the Roman world, and when the spirit of declamation and dogmatism was at its full height, but who was himself, unlike the dreaming pedants of the schools, a statesman and a soldier of practical and proved ability, well rebuked the malevolent aspersions which he heard continually thrown upon the memory of the great conqueror of the East.

He truly says:

Let the man who speaks evil of Alexander not merely bring forward those passages of Alexander’s life which were really evil but let him collect and review all the actions of Alexander, and then let him thoroughly consider first who and what manner of man he himself is, and what has been his own career; and then let him consider who and what manner of man Alexander was, and to what an eminence of human grandeur he arrived. Let him consider that Alexander was a king, and the undisputed lord of the two continents, and that his name is renowned throughout the whole earth.

Let the evil-speaker against Alexander bear all this in mind, and then let him reflect on his own insignificance, the pettiness of his own circumstances and affairs, and the blunders that he makes about these, paltry and trifling as they are. Let him then ask himself whether he is a fit person to censure and revile such a man as Alexander. I believe that there was in his time no nation of men, no city, nay, no single individual with whom Alexander’s name had not become a familiar word. I therefore hold that such a man, who was like no ordinary mortal, was not born into the world without some special providence.”

And one of the most distinguished soldiers and writers, Sir Walter Raleigh, though he failed to estimate justly the full merits of Alexander, has expressed his sense of the grandeur of the part played in the world by “the great Emathian conqueror” in language that well deserves quotation:

So much hath the spirit of some one man excelled as it hath undertaken and effected the alteration of the greatest states and commonweals, the erection of monarchies, the conquest of kingdoms and empires, guided handfuls of men against multitudes of equal bodily strength, contrived victories beyond all hope and discourse of reason, converted the fearful passions of his own followers into magnanimity, and the valor of his enemies into cowardice; such spirits have been stirred up in sundry ages of the world, and in divers parts thereof, to erect and cast down again, to establish and to destroy, and to bring all things, persons, and states to the same certain ends which the infinite spirit of the Universal, piercing, moving, and governing all things, hath ordained. Certainly, the things that this King did were marvelous and would hardly have been undertaken by anyone else; and though his father had determined to have invaded the Lesser Asia, it is like enough that he would have contented himself with some part thereof, and not have discovered the river of Indus, as this man did.”

| Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here and below.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.