The Methodist preacher came to an Anglican parish in the spirit and with the language of a missionary going to the most ignorant heathens.

Continuing Wesley Begins Methodism,

our selection from History of England in the Eighteenth Century by William E.H. Lecky published in 1890. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Wesley Begins Methodism.

Time: 1738

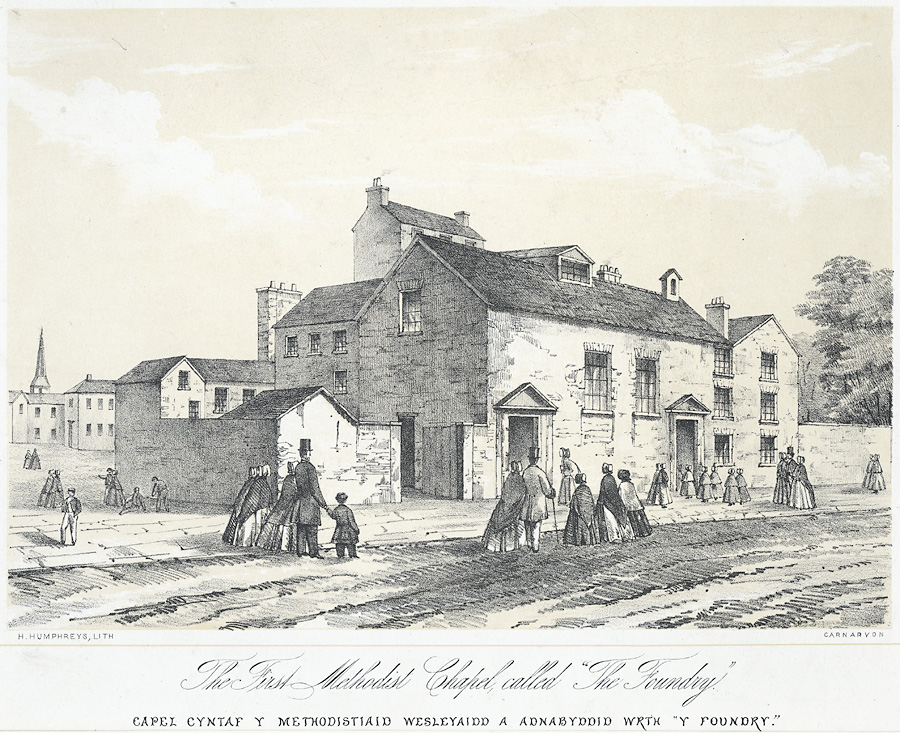

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

It was no less characteristic of the indefatigable energy which formed another and a better side of his nature, that immediately after this change he started on a pilgrimage to Herrnhut, the headquarters of Moravianism, in order that he might study to the best advantage what he now regarded as the purest type of a Christian church. He returned objecting to many things, but more than ever convinced of his new doctrine, and more than ever resolved to spend his life in diffusing it. In the course of 1738, the chief elements of the movement were already formed. Whitefield had returned from Georgia. Charles Wesley had begun to preach the doctrine with extraordinary effect to the criminals in Newgate and from every pulpit into which he was admitted. Methodist societies had already sprung up under Moravian influence. The design of each was to be a church within a church, a seed-plot of a more fervent piety, the center of a stricter discipline and a more energetic propagandism, than existed in religious communities at large.

In these societies the old Christian custom of love-feasts was revived. The members sometimes passed almost the whole night in the most passionate devotions, and voluntarily submitted to a spiritual tyranny that could hardly be surpassed in a Catholic monastery. They were to meet every week, to make an open and particular confession of every frailty, to submit to be cross-examined on all their thoughts, words, and deeds. The following, among others, were the questions asked at every meeting: “What known sin have you committed since our last meeting? What temptations have you met with? How were you delivered? What have you thought, said, or done of which you doubt whether it be sin or not? Have you nothing you desire to keep secret?”

Such rules could only have been accepted under the influence of an overpowering religious enthusiasm, and there was much truth in the judgment which the elder brother of John Wesley passed upon them in 1739. “Their societies,” he wrote to their mother, “are sufficient to dissolve all other societies but their own. Will any man of common-sense or spirit suffer any domestic to be in a band engaged to relate to five or ten people anything without reserve that concerns the person’s conscience, how much soever it may concern the family? Ought any married person to be there unless husband and wife be there together?”

From this time the leaders of the movement became the most active of missionaries. Without any fixed parishes they wandered from place to place, proclaiming their new doctrine in every pulpit to which they were admitted, and they speedily awoke a passionate enthusiasm and a bitter hostility in the Church. Nothing, indeed, could appear more irregular to the ordinary parochial clergyman than those itinerant ministers who broke away violently from the settled habits of their profession, who belonged to and worshipped in small religious societies that bore a suspicious resemblance to conventicles, and whose whole tone and manner of preaching were utterly unlike anything to which he was accustomed. They taught in language of the most vehement emphasis, as the cardinal tenet of Christianity, the doctrine of a new birth in a form which was altogether novel to their hearers. They were never weary of urging that all men are in a condition of damnation who have not experienced a sudden, violent, and supernatural change, or of inveighing against the clergy for their ignorance of the very essence of Christianity. “Tillotson,” in the words of Whitefield, “knew no more about true Christianity than Mahomet.” The Whole Duty of Man, which was the most approved devotional manual of the time, was pronounced by the same preacher, on account of the stress it laid upon good works, to have “sent thousands to hell.”

The Methodist preacher came to an Anglican parish in the spirit and with the language of a missionary going to the most ignorant heathens; and he asked the clergyman of the parish to lend him his pulpit, in order that he might instruct the parishioners — perhaps for the first time — in the true Gospel of Christ. It is not surprising that the clergy should have resented such a movement; and the manner of the missionary was as startling as his matter. The sermons of the time were almost always written, and the prevailing taste was cold, polished, and fastidious. The new preachers preached extempore, with the most intense fervor of language and gesture, and usually with a complete disregard of the conventionalities of their profession. Wesley frequently mounted the pulpit without even knowing from what text he would preach, believing that when he opened his Bible at random the divine Spirit would guide him infallibly in his choice. The oratory of Whitefield was so impassioned that the preacher was sometimes scarcely able to proceed for his tears, while half the audience were convulsed with sobs. The love of order, routine, and decorum, which was the strongest feeling in the clerical mind, was violently shocked. The regular congregation was displaced by an agitated throng who had never before been seen within the precincts of the church. The usual quiet worship was disturbed by violent enthusiasm or violent opposition, by hysterical paroxysms of devotion or remorse, and when the preacher had left the parish he seldom failed to leave behind him the elements of agitation and division.

We may blame, but we can hardly, I think, wonder at the hostility all this aroused among the clergy. It is, indeed, certain that Wesley and Whitefield were at this time doing more than any other contemporary clergymen to kindle a living piety among the people. It is equally certain that they held the doctrines of the Articles and the Homilies with an earnestness very rare among their brother-clergymen, that none of their peculiar doctrines were in conflict with those doctrines, and that Wesley at least was attached with an even superstitious reverence to ecclesiastical forms. Yet before the end of 1738 the Methodist leaders were excluded from most of the pulpits of the Church, and were thus compelled, unless they consented to relinquish what they considered a divine mission, to take steps in the direction of separation.

Two important measures of this nature were taken in 1739. One of them was the creation of Methodist chapels, which were intended, not to oppose or replace, but to be supplemental and ancillary to, the churches, and to secure that the doctrine of the new birth should be faithfully taught to the people. The other, and still more important event, was the institution by Whitefield of field-preaching. The idea had occurred to him in London, where he found congregations too numerous for the church in which he preached, but the first actual step was taken in the neighborhood of Bristol. At a time when he was thus deprived of the chief normal means of exercising his talents his attention was called to the condition of the colliers of Kingswood.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.