Wesley peremptorily refused to leave Oxford, and the reason he assigned was very characteristic.

Continuing Wesley Begins Methodism,

our selection from History of England in the Eighteenth Century by William E.H. Lecky published in 1890. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Wesley Begins Methodism.

Time: 1738

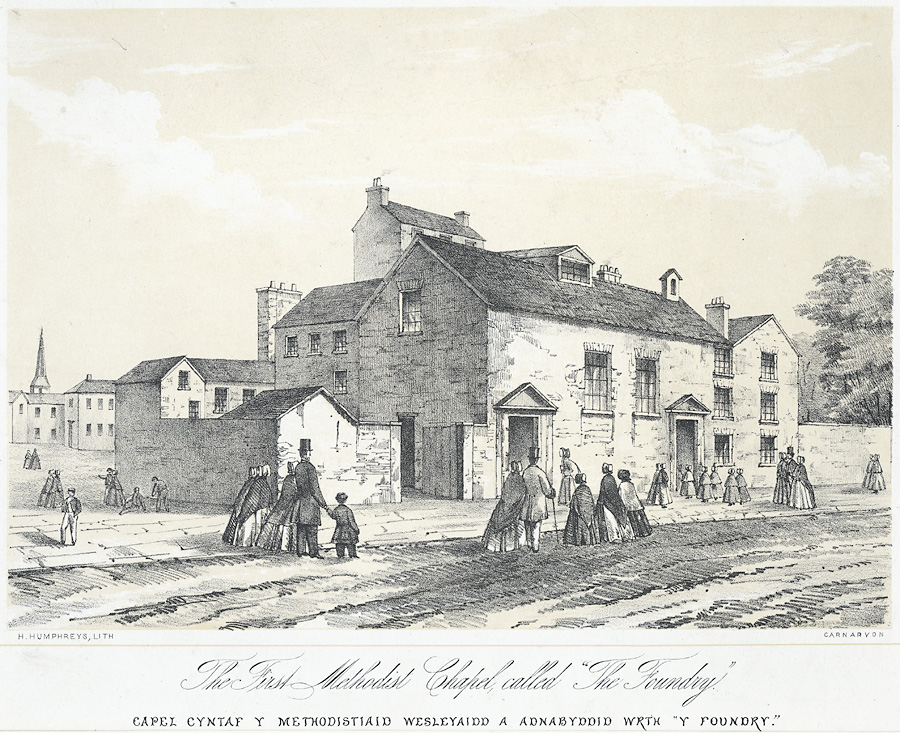

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

There, too, above all, was George Whitefield, in after-years the greatest pulpit orator of England. He was born in 1714, in Gloucester, in the Bell Inn, of which his mother was proprietor, and where upon the decline of her fortunes he was for some time employed in servile functions. He had been a wild, impulsive boy, alternately remarkable for many mischievous pranks and for strange outbursts of religious zeal. He stole money from his mother, and he gave part of it to the poor. He early declared his intention one day to preach the Gospel, but he was the terror of the Dissenting minister of his neighborhood, whose religious services he was accustomed to ridicule and interrupt. He bought devotional books, read the Bible assiduously, and on one occasion, when exasperated by some teasing, he relieved his feelings, as he tells us, by pouring out in his solitude the menaces of Psalm cxviii; but he was also passionately fond of card-playing, novel-reading, and the theatre; he was two or three times intoxicated, and he confesses with much penitence to “a sensual passion” for fruits and cakes. His strongest natural bias was toward the stage. He indulged it on every possible occasion, and at school he wrote plays and acted in a female part.

Owing to the great poverty of his mother, he could only go to Oxford as a servitor, and his career there was a very painful one. St. Thomas à Kempis, Drelincourt’s Defense against Deaths, and Law’s devotional works had all their part in kindling his piety into a flame. He was haunted with gloomy and superstitious fancies, and his religion assumed the darkest and most ascetic character. He always chose the worst food, fasted twice a week, wore woollen gloves, a patched gown, and dirty shoes, and was subject to paroxysms of a morbid devotion. He remained for hours prostrate on the ground in Christ Church Walk in the midst of the night, and continued his devotions till his hands grew black with cold. One Lent he carried his fasting to such a point that when Passion Week arrived he had hardly sufficient strength to creep upstairs, and his memory was seriously impaired. In 1733 he came in contact with Charles Wesley, who brought him into the society. To a work called The Life of God in the Soul of Man, which Charles Wesley put into his hands, he ascribed his first conviction of that doctrine of free salvation which he afterward made it the great object of his life to teach.

With the exception of a short period in which he was assisting his father at Epworth, John Wesley continued at Oxford till the death of his father, in 1735, when the society was dispersed, and the two Wesleys soon after accepted the invitation of General Oglethorpe to accompany him to the new colony of Georgia. It was on his voyage to that colony that the founder of Methodism first came in contact with the Moravians, who so deeply influenced his future life. He was surprised and somewhat humiliated at finding that they treated him as a mere novice in religion; their perfect composure during a dangerous storm made a profound impression on his mind, and he employed himself while on board ship in learning German, in order that he might converse with them. On his arrival in the colony he abandoned, after a very slight attempt, his first project of converting the Indians, and devoted himself wholly to the colonists at Savannah. They were of many different nationalities, and it is a remarkable proof of the energy and accomplishments of Wesley that, in addition to his English services, he officiated regularly in German, French, and Italian, and was at the same time engaged in learning Spanish, in order to converse with some Jewish parishioners.

His character and opinions at this time may be briefly described. He was a man who had made religion the single aim and object of his life, who was prepared to encounter for it every form of danger, discomfort, and obloquy; who devoted exclusively to it an energy of will and power of intellect that in worldly professions might have raised him to the highest positions of honor and wealth. Of his sincerity, of his self-renunciation, of his deep and fervent piety, of his almost boundless activity, there can be no question. Yet with all these qualities he was not an amiable man. He was hard, punctilious, domineering, and in a certain sense even selfish. A short time before he left England, his father, who was then an old and dying man, and who dreaded above all things that the religious fervor which he had spent the greater part of his life in kindling in his parish should dwindle after his death, entreated his son in the most pathetic terms to remove to Epworth, in which case he would probably succeed to the living, and be able to maintain his mother in her old home.

Wesley peremptorily refused to leave Oxford, and the reason he assigned was very characteristic. “The question,” he said, “is not whether I could do more good to others there than here; but whether I could do more good to myself, seeing wherever I can be most holy myself there I can most promote holiness in others.” “My chief motive,” he wrote when starting for Georgia, “is the hope of saving my own soul. I hope to learn the true sense of the Gospel of Christ by preaching it to the heathen.” He was at this time a High-Churchman of a very narrow type, full of exaggerated notions about church discipline, extremely anxious to revive obsolete rubrics, and determined to force the strictest ritualistic observances upon rude colonists, for whom of all men they were least adapted. He insisted upon adopting baptism by immersion and refused to baptize a child whose parents objected to that form. He would not permit any non-communicant to be a sponsor, repelled one of the holiest men in the colony from the communion-table because he was a Dissenter; refused for the same reason to read the burial-service over another; made it a special object of his teaching to prevent ladies of his congregation from wearing any gold ornament or any rich dress, and succeeded in inducing Oglethorpe to issue an order forbidding any colonist from throwing a line or firing a gun on Sunday. His sermons, it was complained, were all satires on particular persons. He insisted upon weekly communions, desired to rebaptize Dissenters who abandoned their Nonconformity, and exercised his pastoral duties in such a manner that he was accused of meddling in every quarrel and prying into every family.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.