From him Wesley for the first time learned that form of the doctrine of justification by faith which he afterward regarded as the fundamental tenet of Christianity.

Continuing Wesley Begins Methodism,

our selection from History of England in the Eighteenth Century by William E.H. Lecky published in 1890. The selection is presented in five easy 5 minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in Wesley Begins Methodism.

Time: 1738

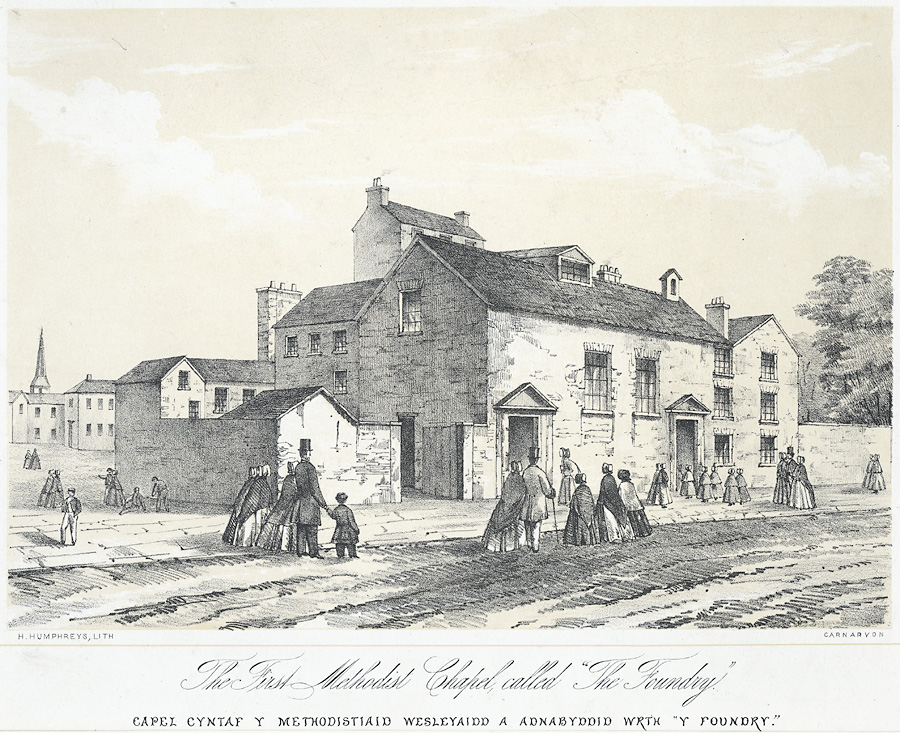

Public domain image from Wikipedia.

A more unpropitious commencement for a great career could hardly be conceived. Wesley returned to England in bad health and low spirits. He redoubled his austerities and his zeal in teaching, and he was tortured by doubts about the reality of his faith. It was at this time and in this state of mind that he came in contact with Peter Boehler, a Moravian teacher, whose calm and concentrated enthusiasm, united with unusual mental powers, gained a complete ascendency over his mind. From him Wesley for the first time learned that form of the doctrine of justification by faith which he afterward regarded as the fundamental tenet of Christianity. He had long held that in order to be a real Christian it was necessary to live a life wholly differing from that of the world around him, and that such a renewal of life could only be effected by the operation of the divine Spirit; and he does not appear to have had serious difficulties about the doctrine of imputed righteousness, although the ordinary evangelical doctrine on this matter was emphatically repudiated and denounced by Law.

From Boehler he first learned to believe that every man, no matter how moral, how pious, or how orthodox he may be, is in a state of damnation, until, by a supernatural and instantaneous process wholly unlike that of human reasoning, the conviction flashes upon his mind that the sacrifice of Christ has been applied to and has expiated his sins; that this supernatural and personal conviction or illumination is what is meant by saving faith, and that it is inseparably accompanied by an absolute assurance of salvation and by a complete dominion over sin. It cannot exist where there is not a sense of the pardon of all past and of freedom from all present sins. It is impossible that he who has experienced it should be in serious and lasting doubt as to the fact; for its fruits are constant peace — not one uneasy thought; “freedom from sin — not one unholy desire.” Repentance and fruits meet for repentance, such as the forgiveness of those who have offended us, ceasing from evil and doing good, may precede this faith, but good works in the theological sense of the term spring from, and therefore can only follow, faith.

Such, as clearly as I can state it, was the fundamental doctrine which Wesley adopted from the Moravians. His mind was now thrown, through causes very susceptible of a natural explanation, into an exceedingly excited and abnormal condition and he has himself chronicled with great minuteness in his journal the incidents that follow. On Sunday, March 5, 1738, he tells us that Boehler first fully convinced him of the want of that supernatural faith which alone could save. The shock was very great, and the first impulse of Wesley was to abstain from preaching, but his new master dissuaded him, saying: “Preach faith till you have it; and then because you have faith you will preach faith.” He followed the advice, and several weeks passed in a state of extreme religious excitement, broken, however, by strange fits of “indifference, dullness, and coldness.” While still believing himself to be in a state of damnation, he preached the new doctrine with such passionate fervor that he was excluded from pulpit after pulpit. He preached to the criminals in the jails. He visited, under the superintendence of Boehler, some persons who professed to have undergone the instantaneous and supernatural illumination. He addressed the passengers whom he met on the roads or at the public tables in the inns. On one occasion, at Birmingham, he abstained from doing so, and he relates, with his usual imperturbable confidence, that a heavy hailstorm which he afterward encountered was a divine judgment sent to punish him for his neglect.

This condition could not last long. At length, on May 24th, a day which he ever after looked back upon as the most momentous in his life — the cloud was dispelled. Early in the morning, according to his usual custom, he opened the Bible at random, seeking for a divine guidance, and his eye lighted on the words, “There are given unto us exceeding great and precious promises, even that we would be partakers of the divine nature.” Before he left the house he again consulted the oracle, and the first words he read were, “Thou art not far from the kingdom of God.” In the afternoon he attended service in St. Paul’s Cathedral, and the anthem, to his highly wrought imagination, seemed a repetition of the same hope. The sequel may be told in his own words: “In the evening I went very unwillingly to a society in Aldersgate Street, where one was reading Luther’s preface to the Epistle to the Romans. About a quarter before nine, while he was describing the change which God works in the heart through faith in Christ, I felt my heart strangely warmed; I felt I did trust in Christ, Christ alone for salvation; and an assurance was given me that he had taken away my sins, even mine, and saved me from the law of sin and death. I began to pray with all my might for those who had in a more especial manner despitefully used me and persecuted me. I then testified openly to all what I now first felt in my heart.”

Pictures of this kind are not uncommon in the lives of religious enthusiasts, but they usually have a very limited interest and importance. It is, however, scarcely an exaggeration to say that the scene which took place at that humble meeting in Aldersgate Street forms an epoch in English history. The conviction which then flashed upon one of the most powerful and most active intellects in England is the true source of English Methodism. Shortly before this, Charles Wesley, who had also fallen completely under the influence of Boehler, had passed through a similar change; and Whitefield, without ever adopting the dangerous doctrine of perfection which was so prominent in the Methodist teaching, was at a still earlier period an ardent preacher of justification by faith of the new birth. It was characteristic of John Wesley that ten days before his conversion he wrote a long, petulant, and dictatorial letter to his old master, William Law, reproaching him with having kept back from him the fundamental doctrine of Christianity, and intimating in strong and discourteous language his own conviction, and that of Boehler, that the spiritual condition of Law was a very dangerous one.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

We want to take this site to the next level but we need money to do that. Please contribute directly by signing up at https://www.patreon.com/history

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.